After the second world war many people in Europe and the United States turned to the East for inspiration. The established Christian Churches were in decline. People evolved from being security seekers to self-fulfilment seekers. Emphasis fell on the development of one’s full personal potential. Floating on a mix of higher economic prosperity and secular erosion of traditional religion people felt attracted to the ancient philosophies and mysterious beliefs found in Asia.

In this chapter I will outline our experience with Catholics caught up in some typical eastern movements. As elsewhere the real names of the individuals involved have been changed.

The Hare Krishna Movement

In August 1995 an anxious mother rang us up from Birmingham. Her eldest 23-year old son Martin had entered Hare Krishna some months before. He now lived in their community. To add to her worry, Martin was putting pressure on Rob to join him. Rob was her second son, 17 years old . . .

What was it all about?

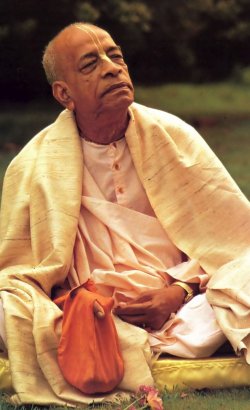

Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada

The Hare Krishna movement aims at drawing people into religious communes that practise intense mystical devotion to the Hindu God Krishna. It was founded by Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Born in Calcutta in 1896 and having learned management skills in a pharmaceutical firm, he became a student of Guru Gosvami in 1922. Gosvami was of the opinion that Krishna-consciousness should be spread throughout the world and he instilled this idea into the mind of his willing and able disciple. Prabhupada began by translating Vedic literature into English through a fortnightly magazine. Soon he enlarged on the contents by adding imaginative commentaries, which he published as books. Half a century of failures and hard work prepared him for the boldest step of his life: his mission to America when he was 70 years old.

Prabhupada arrived in New York on a freighter in 1965. He was penniless. For some months he struggled for survival. But his total commitment, his communicative talent and the religious climate in the United States ensured a complete success. When he died, in 1977, he left behind a flourishing organisation with more than 100 centres all over the world. “A small man wants to make himself happy”, the Swami said, “a bigger man his own family: a truly great man the whole world.”

What was so compelling in Prabhupada’s message that thousands of youngsters were willing to shave their heads bald, don saffron robes, live in ashrams and roam the streets with begging bowls, singing “Rama is God, Krishna is God”? The evidence is baffling. God, we are told, revealed himself in Krishna. Krishna is our best friend. He is the only person who can save us from all evil. “Krishna-consciousness” is, in fact, what Hindus call an approach to God through bhakti, through devotion. One comes close to Krishna by loving him with all one’s heart, singing to his honour and living a dedicated life. What went wrong in Christianity that this was seen as something extraordinary and new?

Prabhupada put out an enormous volume of print during the 11 years of his western mission. His master, Gosvami, once drew a drum and a printing press on the same sheet of paper. “The drum (traditional instrument of Krishna preaching) can be heard throughout the village”, he had said, “but the press resounds through whole continents”. Prabhupada heeded this advice and produced 40 books, mostly lengthy commentaries on classical texts. Readers are expected to master a completely new language. The Sri Caitanva-Caritamrta, for instance, introduces at least 400 technical Sanskrit terms in its 600 pages. The life story of Krishna is riddled with phrases such as: “Because You are the original person, You are therefore described in the Gopala-tapani, as well as in the Brahma-sanhita, as govindam-purusam”.

To return to Martin, who became a Hare Krishna monk, there was little we could do apart from consoling the family and providing good information to prevent Martin’s younger brothers from joining too. We had the same experience with other Hare Krishna members. They lived in a dream world of endless devotional bhajans and rituals.

Sahaja Yoga

In October 1993 we were approached by Claire, a woman in her forties who, with her husband and young daughter, had been a dedicated member of Sahaja Yoga for many years. Some negative experiences in the cult had put doubts in her mind. Moreover, visits to a Catholic church in Italy had deeply impressed her.

What is Sahaja Yoga, you may wonder?

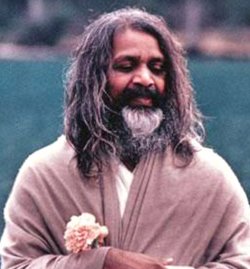

Mataji Nirmala Devi Srivastava

Followers of Sahaja Yoga practise meditation by sitting in front of a photograph of their Guru. By stretching their hands towards the picture they establish spiritual contact with her. The Guru’s name is Mataji Nirmala Devi Srivastava, or Mataji (‘mother’) for short.

Mataji was born to Christian parents at Chindawara in Central India in 1923, one of eleven children. Mahatma Gandhi recognised her special quality very early and asked her to stay with him. For years she worked with him, teaching his message of humility. She married an Indian U.N. official, had children and grandchildren and lived in London for some years. Although she felt from a early age that she was divine, her revelation only came in 1970 when she discovered the spiritual force of kundalini which could be released to give self-awareness. On this she built Sahaja Yoga.

Sahaja may, perhaps, be translated as complete naturalness. The whole of God’s creation is Sahaja and its ultimate realization is Sahaja Yoga. It is a recognition of the identity of spirit and matter, subject and object. God has endowed humankind with his shakti (divine power) and humans have to know him and realise him through kundalini awakening.

Kundalini is said to be a dormant energy lying coiled at the base of the spine. When it is awakened it rises up. Seven chakras (centres of being) along the spine are enlightened one by one. When the final stage at the top of the head has been reached, a cool breeze is experienced on the hands. This leads to a form of ecstasy which the Hevajra Tantra describes as follows:

From ecstasy comes some bliss, from perfect ecstasy yet more. From the ecstasy of cessation comes a passionless state. The ecstasy of Sahaja is finality. The first comes by desire for contact, the second by desire for bliss, the third from the passing of passion, and by this means the Sahaja is realized. Perfect ecstasy is samsara [mystic union]. The ecstasy of cessation is nirvana. Then there is a plain ecstasy between the two. Sahaja is free of them all. For there is neither desire nor absence of desire, nor a middle to be obtained.

You will find a full description of Sahaja Yoga in my article Praying with the Body.

The good news was that Mother Mataji sold peace and love – for free. She was not interested in money. She saw herself as a guide who wanted her disciples to realise their own powers to be happy and to become masters of themselves, and thus of the world they lived in.

After a course of religious instruction Claire and her family were baptised in a Catholic parish. We remained in touch with them for a number of years.

Subud

A number of Catholics approached us for advice on the Muslim meditation technique of Subud. One of them was a priest in Cardigan, Wales, who told us some of his parishioners believed they could follow this practice while remaining in the Church. Which raised the question: what is Subud, and how does it function?

Muhammad Subuh Widjojo

Subud stands for sushila buddhi dharma, which means ‘good character in accordance with the rule of supreme intelligence’ (= God). The movement was founded by Muhammad Subuh Widjojo, an Indonesian citizen. He was popularly known as Bapak. Bapak claimed to have received visions that revealed the value of latihan, the meditation technique he felt called upon to spread throughout the world.

Latihan (Indonesian for ‘exercise’) was practised twice a week in half-hourly communal sessions. Members would initially sit in silence, then stand up to allow the release of the full force of spiritual energy. This would be felt as an inner vibration. It might make one move one’s body in various directions, uttering words in often unknown languages. The latihan was said to unleash the experience of the Divine in oneself, of the ‘Spirit’, – which Bapak stated was the inner core of all religions. That is why he taught that one could continue to follow one’s own religious practices: they were, after all, only the outer forms of worship. He also claimed that Subud was ‘free of dogma’.

But in a letter to the Welsh parish priest I expressed a word of caution:

“SUBUD’s latihan practice, though newly formulated by Bapak, incorporates ancient oriental beliefs and experiences that can be helpful for discerning people. The same applies to yoga exercises, zen meditation, sufi practices, and so on. I regard all these things as part of our general human/spiritual heritage which we, as Christians, should also take seriously. However, what is sometimes overlooked is that the techniques are often offered to people as part of a wider ‘package’ that includes much more. It is one thing for well-trained monks to use latihan or raja yoga which they lift out from its context, quite another thing for ordinary Christians to join movements that use such techniques.”

“For one thing, within such movements, – and this applies also to Subud -, there is a fair amount of ‘indoctrination’ going on, even though the movement officially claims to be ‘free of dogma’. The ‘doctrine’ consists in religious conceptions that at times conflict with our Christian faith; for instance, that sin is no more than a disorder between various natural forces; or that a spontaneous experience of the divine, obtained through the technique, is more important than our

being healed sacramentally by Christ.”

“With regard to Subud, for example, members who attend groups rarely just go along for the latihan alone. They read and buy Bapak’s talks which are printed up and sold, as I know from people who have been members for some time. Bapak holds that Subud offers the ‘inner spark’ of religion which is missing from most of the mainstream religions today. He recommends that one continues to practise one’s religion, for that is ‘the outer form of worship’. If such instruction is interpreted from within a Christian perspective, in the sense of: “I must internalise and deepen my Christian faith”, not much harm is done; in fact, it might help some individual seeker. More often than not Christian believers may come to the conclusion that their own latihan prayer is more important than, say the Eucharist. After all, why did Christ not teach the latihan? I know cases where this actually happened.”

“The worrisome outcome is strengthened by relationships to non-Catholic or non-Christian members who gradually replace the function of the Church as one’s Christian community. To remain with our example, Subud is a ‘family’ with Bapak as the ‘father’. Some of the members are ‘helpers’ who guide members who are ‘tested’ or in a ‘crisis’. Subud collects money for its own projects. There are meetings and functions. In itself, there can be no objection to this, of course, and people belong to all kinds of clubs and organisations. The point I am making is that, were we to tell people there is no harm in joining Subud, we may well, in actual fact, point them the way out of the Church.”

Transcendental Meditation

Priests and individual Catholics approached us at various times with a similar question about Transcendental Meditation, ‘TM’ for short. “Why would the practice of TM interfere with being a good Catholic?” TM’s founder, in fact, the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi claimed that his technique of prayer did not affect one’s faith or denomination.

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

As a student of physics at Allahabad, Mahesh met Gurudev, became his disciple and imbibed Shankara teaching. After his master’s death, Mahesh announced his new movement in 1957. He found little response in India, but his brief, unsuccessful tutorship of the Beatles gave him welcome publicity. Like others before him, Mahesh rolled his few belongings in a blanket and travelled via Singapore, Hong Kong and Hawaii to San Francisco.

Once in the States, Mahesh showed a keen understanding of what would ‘go down’ in the West. He stripped his message of all traditional trappings and presented it as a simple meditation technique adapted to American activist life. The approach consists in mentally repeating a ‘sacred word’, a mantra, until the mind is temporarily ‘switched off’. It is a so-called obliteration technique, not unlike staring at a fixed point or looking into a flame. By over-concentration on a particular sensation, the mind lets go of its conscious grip which produces sensations of release and deeper consciousness. Students of TM are told that two periods of 20 minutes a day will transform their lives.

The Maharishi’s genius consisted in surrounding this simple technique with an elaborate aura of mystique and expectation. To keep control firmly in hand, he decreed that each person needs his own, specific mantra, which can be assigned only by accredited teachers of the organisation. A considerable fee is demanded on enrolment. Impressive scientific studies proclaim TM’s visible effects on alpha-rhythm in the brain, on breathing, the heart beat, blood pressure and reducing weight. TM is said to relieve insomnia, increase resistance to disease, improve perception and creativity. The crime rate is down in cities where TM is practised, and so on. Adepts of the technique may look forward to acquiring one or more siddhis, miraculous powers, such as levitation, seeing things hidden from view, becoming invisible, attaining pure consciousness.

The best gimmick of all, in my view, is the term “Transcendental Meditation” itself which is sure to attract intellectuals hungry for prayer. Whether they really learn to pray is quite a different question. The technique, of course, does pave the way for some of the initial stages of prayer: for silence, for withdrawal from everyday distractions, for seeking release. But to Christians, prayer means much more than a super-conscious state of mind, it means a loving response to God who loved us first and who showed his love through Jesus Christ. Many Catholics, won over by the first positive effects of the technique — which they would have gained equally in any meditation of silence and withdrawal — are too easily convinced that it helps them live their Christian life more fully.

Quite a few Catholics I knew did, in spite of initial protestations, give up their practice in exchange for the religion the Maharishi offers. Their belief in Christ faded away in a search far the unfathomable Hindu neti-neti; they found a substitute morality in the guru’s plan of reforming the world and an alternative “church” in his organisation. When A. Campbell, propagator of TM in Great Britain, maintained that St John of the Cross and the Maharishi are on the same wavelength, he forgot to point out that the Spanish mystic drew his inspiration from Sacred Scripture and from a profound devotion to Christ’s humanity. But A. Campbell’s autobiography, as also the life story of so many TM converts, does raise a valid question: why should someone who received an excellent Catholic education in a Jesuit college turn dissatisfied from communion with the Church and then find “the fulfilment of his deepest desires” in a Hindu meditation technique?

I have unfolded the full story behind TM in an 1984 article of mine: the Mantra Mystery.

Other movements from the East

During the ten years Jackie and I provided pastoral guidance to families involved in the new movements, we encountered many more Eastern cults. It is not necessary for me to describe all of them. They included the Ananda Marga led by Anandamurti; the Divine Light Mission, brainchild of Guru Maharaj Ji; Lifewave under Herbert John Yarr; People Searching Inside founded by Joseph Dippong; Brahma Kumaris; persons involved in Zen Buddhism; others practising I Ching; and a group following Witness Lee.

Next chapter: Masters of Deception

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage