Returned Missionaries

The largest group of Mill Hill men I had to care for were missionaries living in our retirement homes and semi-retired members who had come back from the missions and were now involved in part-time pastoral ministries. They were a wonderful assortment of men. Champions and heroes of the mission field. On my annual tour of the regions I would meet as many of them as I could individually, face to face.

Some of them found it difficult to settle back into their home countries, as I will explain later. But most of them were doing well. I had learned to give them time to tell of their experiences. And their tales proved fascinating. I would often sit spellbound, admiring their courage and determination as they had overcome incredible obstacles. I will briefly recount some of their stories to give you a flavour of what they contained, omitting names to avoid compromising anyone.

A Dutch missionary from Kuching in Serawak narrated about his encounters with Japanese soldiers during World War II. On one occasion he was lying in a ditch, bullets whizzing past his ears. “I was frozen stiff with fear”, he told me. He then spent 4 years in a Japanese POW camp. When the war ended, a Japanese officer conducted seven Mill Hill missionaries to a lonely place in the jungle and executed them. By a lucky set of circumstances our man had escaped . . .

A Tyrolese had built up parishes in various remote places on Iloilo Island in the Philippines. One day, he told me, a colleague in a neighbouring parish had died a week before. He travelled to the man’s place and found the man had already been buried. “There was something strange about it”, he said. “At times people were kidnapped. I did not know whom to trust. So I made them dig up the grave. I found indeed that my colleague lay there, the body still in reasonably good state. But during the few days in the grave, his short white beard had grown longer. It came down his whole body including the feet!” I thought it might have been a fungus, but I did not tell him so.

Seminar for retired missionaries at Mill Hill College, 25 September – 5 October 1978

An old Dutchman narrated how he had opened a vast part of Kenya to Christianity. In an area that predominantly belonged to one tribe, he established many parishes, opened schools, brought in Sisters to run hospitals and clinics. As the founder of those institutions, he was locally hailed as everyone’s ‘Father’. But it was Mill Hill policy not to allow members to retire on the missions. This was done to ensure good care for the individual and not to place an extra burden on the local diocese. When, on account of failing health and incipient dementia, he was told to retire to the Netherlands, the Prime Minister of Kenya had decorated him and paid for a first-class ticket in the plane taking him back to Amsterdam. But our man had rebelled. After spending a few months in our retirement home Vrijland, he had slipped out and flown back to Nairobi. More heartrending moments followed when he was subsequently brought out a second time to return to Vrijland . . .

Another Dutch priest from Limburg had acquired fame as an accomplished builder of churches in Bamenda diocese. When Christianity expanded, large congregations had sprung up that needed appropriate churches. “The first church I built collapsed”, he told me. “So when I came back to Sittard on home leave, I consulted a number of contractors. They allowed me to work on their building sites sharing work with professional masons. Those men taught me, for instance, that brick walls should be absolutely straight, otherwise they would not be able to carry the weight. So I returned with a lead weight to my mission which has served me extremely well.”

An English missionary had survived the communist uprising in Zaire. Rebels had captured various towns and villages in the diocese of Basankusu where Mill Hill men worked. They would routinely round up any priest they found and execute them in public. In fact, four of our missionaries had been killed in that way, including one of my classmates. The man who was telling the story had escaped by hiding in the bush, and later paddling his way out in a canoe on treacherous rivers flowing through a network of swamps . . .

I could multiply stories like this. When the Masai in Kenya began to change their life style from nomadic to sedentary, Mill Hill missionaries were there, learning their difficult language and establishing schools for their children. Mill Hill pioneers among the Maori in New Zealand became experts in Maori culture and helped the people integrate with English-speaking society. Mill Hill missionaries stayed with the Nuer, Dinka and Shilluk tribesmen when these were plundered by Arabs from the North of Sudan. One of them, an American, spent months in captivity, being led around by a gang of Arab robbers from one hiding place to another. When the Muslim government of Malaysia expelled 40 Mill Hill missionaries from Kota Kinabalu in Serawak, one of them went underground for a number of years to supply mission stations with priestly services. The list goes on . . .

But my ministry to our returned missionaries extended to more than admiringly listen to their stories. I had to open their minds to the new religious climate in the West.

Understanding the Church

I became Director of the Home Regions 17 years after my ordination. I had spent most of those years working in India. On my return to Europe I was amazed at the changes that had taken place and were taking place. Small wonder that other returning missionaries, often after 30 or 40 years on the missions, found it difficult to absorb the implications.

I had looked forward to my encounter with Fr Norbert Pryor in our retirement home in Freshfield. He had ministered in India for most of his life and some Telugu priests I knew in Andhra Pradesh had been singing his praises. In their eyes he was the example of a perfect priest. The person I met was confused and disgruntled. He fiercely rejected all Vatican II reforms. He refused to ever concelebrate with other priests. “Concelebration has been invented for the comfort of sacristans”, he complained.

Fr Anton Zuure, retired in Vrijland, had been a caring parish priest on an island in Lake Victoria. The area belonged to Jinja diocese in Uganda. “Anton loves devotions”, Bishop Billington of Jinja once told me. “When I offered to send him an assistant to help in his parish, he replied: ‘No! Rather send me a statue of St. Joseph’.” On return to the Netherlands Anton could not cope with the Church he encountered. Being the militant person he was, he joined Dutch reactionary groups that fought against every kind of reform.

But such persons were extremists. The vast majority of returning missionaries suffered the pain in silence. They listened to liberal radio programmes with disbelief. They looked at empty churches in quiet alarm. What had happened to Europe? Where had triumphant Catholic commitment gone? As one said to me: “I spent most of my life persuading Africans to accept Christ. Now I find my nephews and nieces, in fact the whole younger generation, walking out of church. What’s the use of it all?”

I devoted a lot of my energy to address such questions. I talked to individuals in private meetings. I addressed groups of them in our retirement houses. I organized seminars for the Seniors, as we called them, and for those in their charge. I knew that it was essential for our elderly members to get a better picture of what was going on.

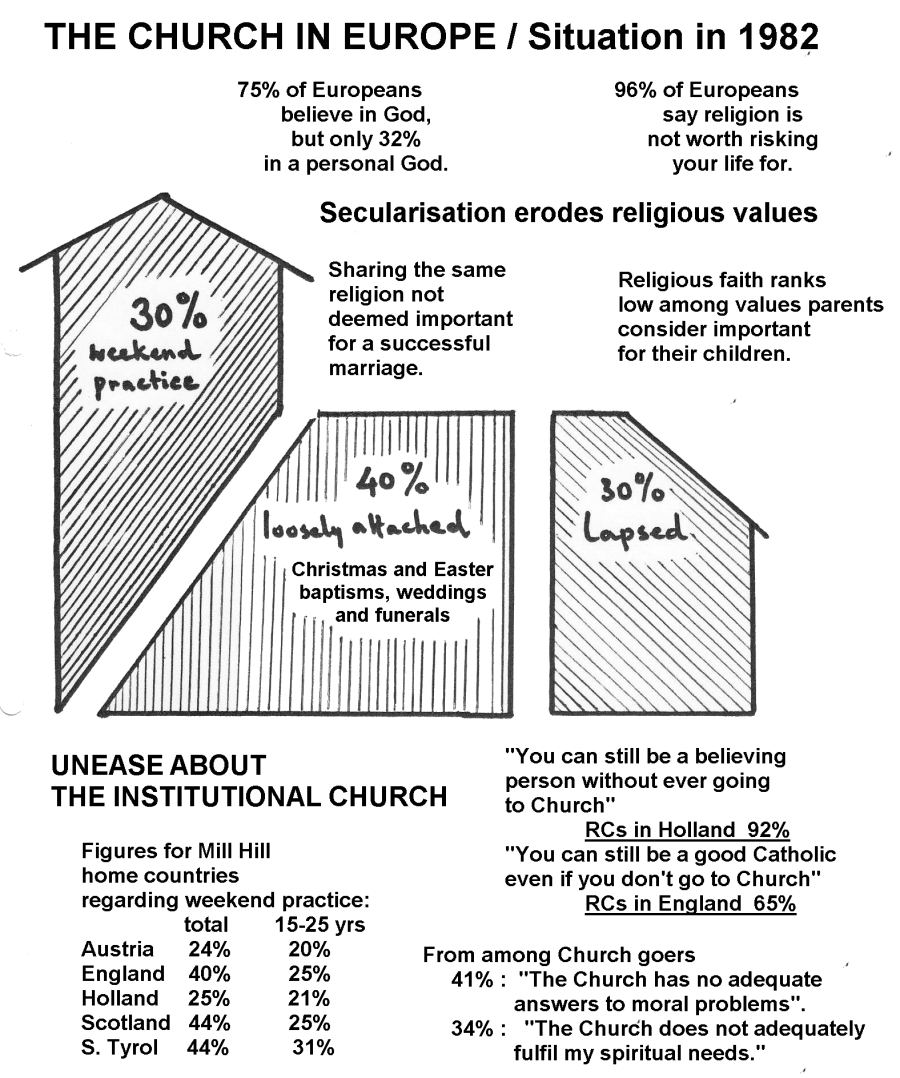

Secularization was a major factor. People were better off financially and socially, and that always causes a loss of interest in religion. Families in previously remote farming villages in Ireland, England, the Netherlands and Tyrol, had become less isolated and so less dependent on the local parish community. The Church itself also was at fault by failing to meet legitimate modern concerns. By totally forbidding artificial contraceptives through Humanae Vitae in 1976, Pope Paul VI was leaving young parents to their own counsel – which they found outside the Church. The Church lost the allegiance of many self-sufficient men and women by its rigidly top-down male-only clerical structure.

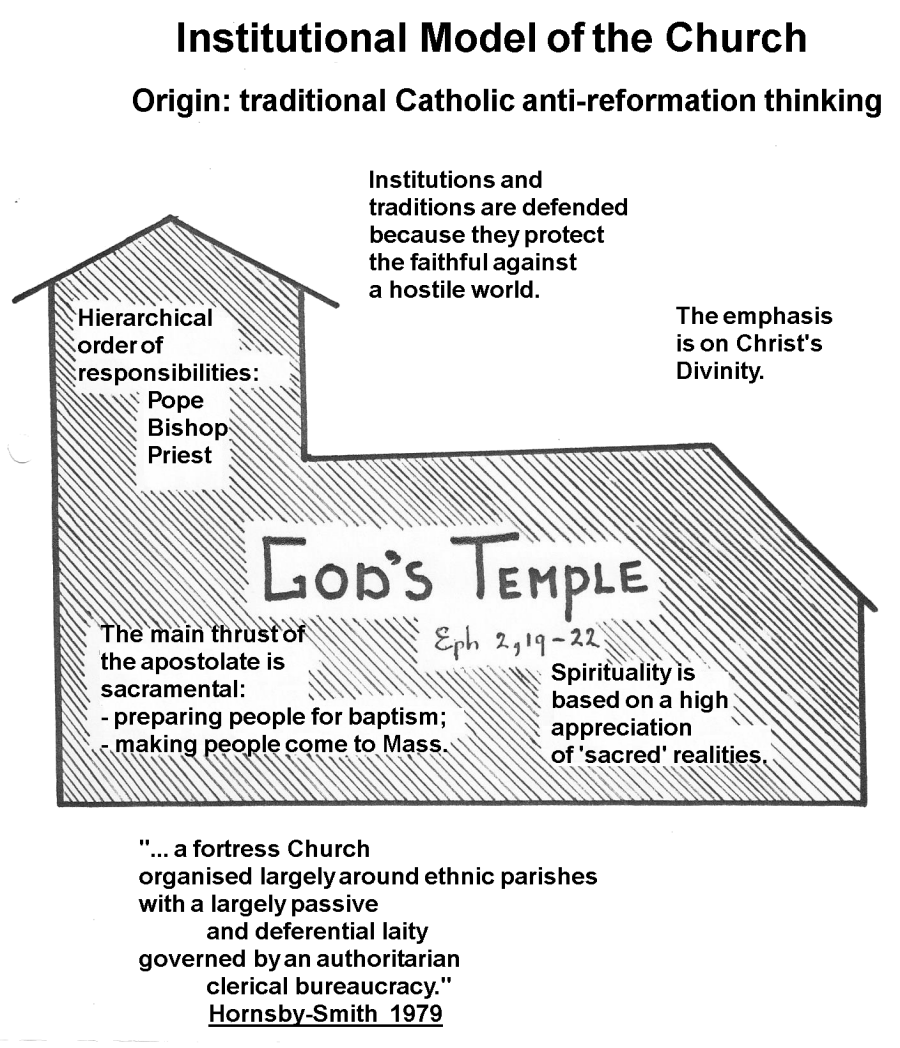

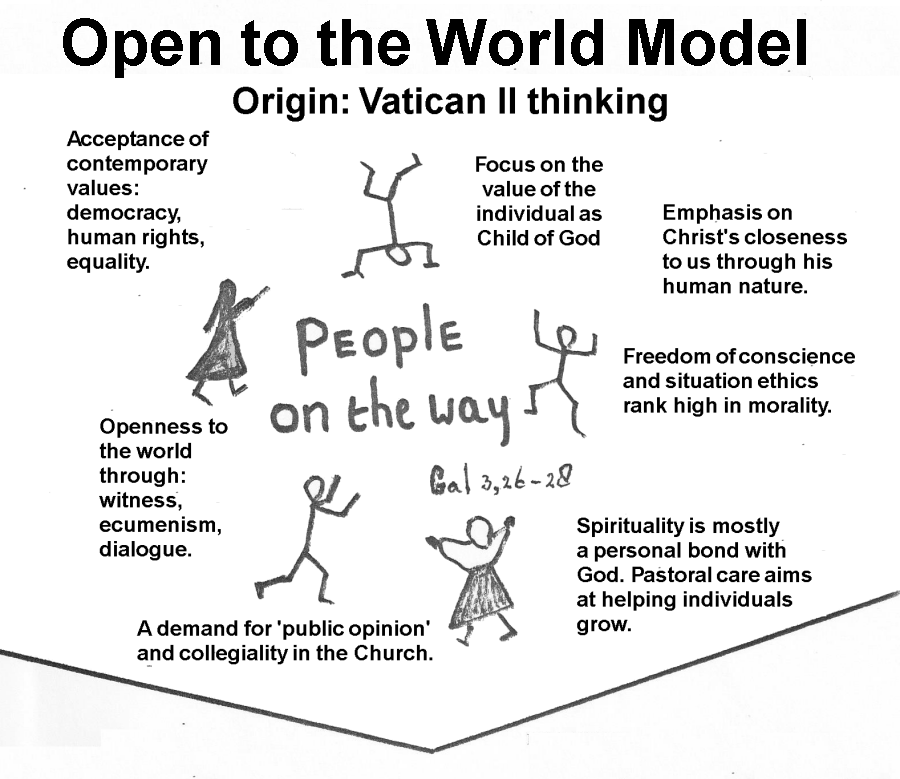

I also tried to explain that another process was going on. Just as the image of the priesthood needed correction through a contemporary model (see previous chapter), so the image of the Church itself called for updating. And this process had received its strongest impulse from the Second Vatican Council itself. The traditional sacramental fortress-church model needed to be supplemented with the Church as being open to the world.

This was especially important for the non-resident members who, in their old age, were still ministering in chaplaincies and parishes. They needed to help new generations of church-goers accept values such as ecumenism with other Christian denominations and dialogue with non-Christian religions. Rather than focusing on restoring the previous sense of dependency in the laity, people had to be encouraged to think for themselves and take on responsibilities in the parish. While criticizing some anti-religious tendencies, positive principles of the modern world should be acknowledged and promoted, such as democracy, human rights and genuine equality for all.

Underlying it all was a major cultural shift. Most people had begun to live in the anonymity of large cities in which you do not know your neighbor, neither the travelers that surround you in the underground on the way to work, nor the crowds you meet in the streets or shopping centres. In past western societies the point of gravity had laid on the communal: on families as a unit, on villages as close-knit communities, on regions as racial tribes. Now the focus fell heavily on the individual: his or her freedom and wellbeing, each person’s specific needs and gifts.

With other Mill Hill leaders I also came to the conclusion that, as a Society, we had failed to give our members the periodic information and updating they needed to do their spiritual and social tasks well. Just as doctors, police, the military, teachers and other professionals, missionaries should be recalled for in-service-training every ten years or so. We started a programme that has been in operation ever since.

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage