In the rehabilitation camp at Tah Muang, Thailand, a make-shift primary school of bamboo huts try to make up for what children had missed in the Japanese camps. For teaching had been forbidden. Carel and I learned how to read and write on scraps of wrapping paper. No textbooks. The only formal education we had received was from my mother and some of her friends talking to us about history, or the geography of Indonesia.

One evening I overheard my father talking to the teacher who had taken charge of ten-year olds like me. They were sitting in wicker chairs on the wooden verandah outside our barracks drinking a glass of Mekong beer. I was sitting some distance away on the wooden planks, my feet dangling over the dusty ground below. The two men did not know I could hear them.

“I’m afraid I’ve bad news”, the teacher told my father. “Hans over there . . . Well, I don’t know.”

“What do you mean?”, my father asked.

“Well, this will disappoint you since you’re a teacher yourself. How shall I put it? Hans will have problems.”

“Why?”

“To put it bluntly: he’s not very gifted. He’s willing enough but slow in the uptake. Hasn’t got it upstairs. Not cut out for study I’d say. Sorry, old chap.”

This damning assessment put a dent in my self consciousness that would remain for a long time. Again and again I had to prove to myself that my critic had been wrong. The first opportunity came a few months later when I joined a village primary school in Baarn, the Netherlands. After some hesitation I had been put into the fifth form, in spite of my lack of proper schooling. A maths teacher made us do multiplication exercises. I completed them faster and better than most others.

“Did you do this yourself?”, the teacher inquired suspiciously. She insisted she wanted to watch me while I was doing the next exercises. She was surprised to see how accurately and quickly I finished the job.

A few months later again, Carel and I were admitted to the top form of a slick city primary school in Utrecht. We were expected to fill in weekly tests based on lecture material and homework. I scored excellent marks. When I joined the missionary college in Hoorn, I soon ranked among the top students. In Haelen I was selected with three others of my class to attempt the Dutch State’s entrance exam for university studies.

The challenge was formidable. Exams in 6 languages: Dutch, Greek and Latin – each requiring 2 written and 1 oral exam; French, German and English – each requiring one written exam. History, geography, algebra and geometry requiring written and oral exams. Since these were public tests, the exams were conducted in central locations by independent teachers and scholars.

Our seminary training followed a grammar school programme that was heavily weighted in favour of languages. Maths therefore posed the challenge. Imagine my surprise – and delight – when in was particularly successful in algebra. During the oral interview the two examiners wanted me to explain graphs.

Myself at the Dutch State Exam at the end of gymnasium in 1953.

“How can you make a graph of graphs?” It was a question I had never been confronted with.

“Ah – you need to make a three-dimensional graph”, I replied.

They kept pressing me with ever more demanding questions. At the end of the exam one of the examiners told me that they were astounded at my grasp of graph theory. And right at the end of the week-long ordeal when each applicant had to face a four-member board of the examination committee I was handed my certificate with a special recommendation.

“Though you also excel in languages”, the chairman of the board told me, “we recommend that you switch to mathematics for which you got full marks. Full marks, I tell you. That is quite rare. You have a natural gift for figures and mental calculations. What line of studies do you have in mind?”

“I want to become a Catholic priest”, I said.

I report all this because it was only this ringing endorsement by an official panel of teachers that laid to rest the lingering doubts I had had about my intelligence. I did not know that the real test of my intelligence was still to come.

Hearing the other side

The two-year philosophy studies in Roosendaal that followed next did not overtax either my capability or my interest. So I began to look for a worthwhile hobby that could absorb my excess energy. I found it in the study of Arabic.

My father, who was a keen linguist, had begun learning Arabic at the time and it struck me that knowing Arabic would be extremely useful in my future dealings with Muslims. Hilaire Belloc, the far-sighted historian, had correctly prophesied that Islam would pose the greatest challenge to Christian mission in years to come. In most territories entrusted to Mill Hill missionaries, such as India, Pakistan, Malaysia and East Africa, this was indeed the case. So I fixed my gaze on dialogue with Islam and on Arabic as a tool in that process.

My father donated to me the best Arabic course books available at the time written by the Jew Jochanan Kapliwatzky. I bought a number of other classic commentaries on Islam. And when I discussed my programme with Arnulf Camps, professor of missiology at the Catholic University of Nijmegen, he urged me to start reading the Qur’an in Arabic with the help of commentaries and translations. “Knowledge of the Qur’an will open many doors to you in Muslim society”, he said.

His advice would prove right during my work in India. The fact that I could read the Qur’an and other Muslim literature in Arabic was to prove a valuable asset in my frequent contacts with Muslims of all kinds. However, there was a problem. The Qur’an had been placed on the Index, the list of forbidden books, by the Vatican authorities in Rome.

When book printing spread in Europe, both civil and religious authorities became aware of the opportunities it presented to rebels and heretics. Various governments, notably those of France and England, declared some books to be forbidden. The Roman Index was first published in 1559 under Pope Paul IV. From 1571 to 1917 it stood under the care of the Vatican Congregation of the Index who kept updating it. And whereas civil authorities by and large relaxed their bans in the course of time, the Roman Index firmly remained in place till 1966.

In its final edition the Index listed 4000 titles. These included works by the greatest European thinkers: Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei, René Descartes, Francis Bacon, John Milton, Blaise Pascal, David Hume, Erasmus, John Scotus Eriugena and many others continuing to our day. Also novels were listed such as The Three Musketeers by Alexander Dumas, and Les Miserables as well as The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Victor Hugo.

The Index affected me because the Qur’an featured prominently on it. I would only be allowed to read it if I were given a dispensation from the Index, Professor Camps told me, which was at times given to scholars for research purposes. Camps wrote a letter of recommendation which I presented to Father Padberg, Rector of Roosendaal College, who in turn approached the local bishop who resided in Breda.

As a result I got a two-year dispensation from the Index. I bought an Arab copy of the Qur’an as well as two English translations by well-known Muslim scholars. So far so good.

Two years later, when I had started my theological studies in Mill Hill College in England, I noticed that the dispensation had expired. Conscientiously I approached Father J. P. Martin, the Rector of the College, with the request to apply to the Archbishop of Westminster, our local bishop, for an extension of the dispensation. Imagine my surprise when a few days later Father Daan Duivesteyn, the Master of Discipline, visited my room.

“We have had a staff meeting”, he said curtly. “We consider it totally inappropriate for an inexperienced theologian like yourself to be dispensed from the index of forbidden books.”

“But that’s ridiculous!”, I protested. “The Qur’an does not pose any risk to my faith. Moreover, if it were to be dangerous, the damage has been done already. I have been reading the Qur’an for two years!”

“Don’t argue!”, he said.

With that, he initiated a thorough search of my room. All my copies of the Qur’an were confiscated. So were a couple of other books, like those by Voltaire and Emmanuel Kant which I did not even know were listed in the Index . . .

The whole affair left a bitter taste in my mouth. Why did the authorities not trust me? And even if the Index was supposed to protect uneducated people, why was it imposed on theologians? Was the whole purpose of studying theology not to examine issues critically, considering arguments for and against?

I began to look more carefully at the way we were taught theology. On all crucial questions the opinions of so-called ‘opponents’ were reported in short summaries. But were we ever exposed to what these ‘opponents’ really said? The answer is: no, not even regarding key questions! We were never actually given to read the spiritual interpretations of the early Gnostics, or the criticism of the Roman interpretation of Christianity by Luther, Calvin, John Knox or Erasmus. It dawned on me that we were expected to swallow the orthodox view wholesale without being allowed a critical evaluation of the true thinking of the ‘opponents’. We were being brainwashed, not really guided to form our own mature appreciation of the issues involved and the reasons why the Catholic position made sense.

I entered a note in my spiritual diary that I would practice absolute honesty and openness in my theology. I made up my mind that no one would stop me studying ‘the other side’ of any issue and this in the actual words of so-called ‘opponents’. Since that time I have regularly bought the classic writings of such ‘opponents’. The collection has swollen to hundreds of volumes and now forms a sizeable part of my library.

4004 BC?

It was my misfortune to have Father Daan Duivesteyn as our main theological lecturer. It soon became clear to me that I could not agree to his conservative stand on many issues. At the centenary of Darwin’s publication of The Evolution of Species, Duivesteyn poured scorn on the whole idea of evolution and rejected it totally as far as human beings are concerned.

By that time I had picked up many outstanding works on evolution that reported extensively on the scientific research that underpinned evolution. I found the arguments in favour of evolution incontrovertible. Nowadays we know that humans and apes share 98% of their genetic code. Genetics had not yet been developed much at that time. But a study by Ralph von Koenigswald on hominids and apes convinced me that a common ancestor was undeniable. “Of 1065 anatomical features, human beings share 396 with chimpanzees, 385 with gorillas and 354 with orang utans”.[i] So much more evidence has come in since then, of course. The point I want to make is that at that time there already was sufficient proof to establish that humans evolved like all other animals.

Duivesteyn saw this as a threat to the special status of the human soul. He quoted at us Pope Pius XII’s encyclical Humani Generis (1950).

“The Teaching Authority of the Church does not forbid that, in conformity with the present state of human sciences and sacred theology, research and discussions, on the part of men experienced in both fields, take place with regard to the doctrine of evolution, in as far as it inquires into the origin of the human body as coming from pre-existent and living matter — for the Catholic faith obliges us to hold that souls are immediately created by God . . . Some however rashly transgress this liberty of discussion, when they act as if the origin of the human body from pre-existing and living matter were already completely certain and proved by the facts which have been discovered up to now and by reasoning on those facts, and as if there were nothing in the sources of divine revelation which demands the greatest moderation and caution in this question.”

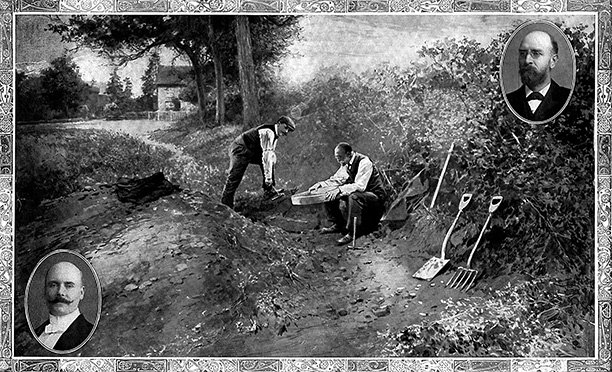

Discovery of the ‘Piltdown Man’ announced in the Illustrated London News in 1913. It was a fake.

Also, it did not help that in 1953 the ‘Piltdown Man’, a supposed fossil of an ancient human skull, was exposed as a forgery. “The whole exercise is utterly preposterous!”, Duivesteyn exclaimed. “Palaeontologists look at a jawbone and tell us how tall he was, what he ate for lunch, how long he had lived and so re-construct a whole human ancestor from a fragment of bone!” Duivesteyn rejected the fundamentalist claim that the world had been created in the year 4004 BC. But he explained the seven-day creation of Genesis as creation in seven lengthy periods.

Anyway, I disagreed with Duivesteyn’s rejection of human evolution, noting the origin of the human soul as something that still needed to be resolved. And this prompted me again to take another resolution.

I refused to simply swallow what lecturers, authors or even church authorities would present to me. As a theologian I myself would be responsible for my own conclusions and convictions, based on the arguments of my own intelligence. I also decided to take scientific research very seriously. I noted in my spiritual diary:

I will have great respect for the positive sciences. In fringe questions that affect both science and theology, I will not accept anything that is not justified also from a scientific point of view. Without the support of the positive sciences where possible, theology, and therefore our faith, miss a solid foundation.

The sciences are, after all, based on the use of human reason. I knew I had good grounds for asserting my support for reason. The First Vatican Council had solemnly declared in 1870:

“Even though faith is above reason, there can never be any real disagreement between faith and reason, since it is the same God who reveals the mysteries and infuses faith, and who has endowed the human mind with the light of reason. God cannot deny himself, nor can truth ever be in opposition to truth.”

The methodical use of reason, as is pursued by the modern sciences, should teach theology a thing or two: the need of a rigorous examination of fact, of the freedom of expression, of methodical doubt, of lateral thinking, of debate and willingness to test unusual ideas.

[i] G.H.R. von Koenigswald, ‘Paleontologie en Menswording’, Evolutie, Spectrum 1959, pp. 142-165.

John Wijngaards, My Story – My Thoughts, Learning to think

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage