In the previous chapter I presented a rough description of Andhra Pradesh, then India’s fifth most populous state. It is a land of paddy fields and semi-deserts, scene of ancient village craft no less than jet-age industries, and harbours all the problems and prospects so characteristic of the motherland. The local people, the Telugus, have their own language and culture, a proud history and venerated traditions. Foreigners tend to think of Indians as one homogeneous race but Telugus are as different from Punjabis, Malayalis or Goans as Scotsmen from Prussians, Spaniards or Corsicans. This distinctive character was also apparent in the domain of religion.

Whereas Christianity made little headway in other parts of India, in this state it encountered a welcoming response. In the 1960s and ‘70s, every year thousands of Telugus applied for baptism. This obviously put a heavy strain on the local church’s resources – a fact that may explain why it was here that the need of a fresh approach was felt so strongly. And I am happy to record that I myself made a substantial contribution to finding a solution. It all began in a follow-up meeting to Vatican II in 1967.

Delegates from the seven dioceses which the State possessed at the time had come together in Kurnool in Anantapur district. After spending an eventful night lying on our mattresses in a boys’ boarding school, we gathered in a classroom where seats and desks had been arranged in a circle. Topic of the meeting was evangelisation. Chairman was the stocky, irritable and unpredictable Bishop of Kurnool Joseph Rajappa.

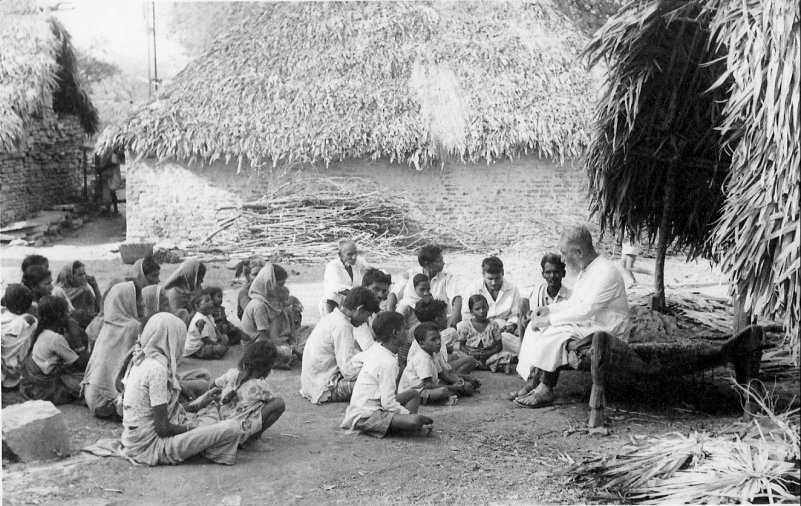

Fr Boon of Kurnool diocese instructing villagers outside their prayer hut.

The priests who were present reported on the steady stream of catechumens who were entering the church. But they expressed dissatisfaction, if not frustration, at the manner in which aid agencies in the West were supporting their apostolate. Common complaints were:

- “My neighbour gets enough money to build a cathedral; I can’t even afford a motorcycle.”

- “For every small request, you have to fill in endless forms or wait for months before it is approved, and for some months more before the money actually arrives. Meanwhile you may have been transferred to another parish.”

- “One only gets aid if one follows the policies of the grant giving agency. I find it easier to apply for a pig sty than for a prayer hut to instruct catechumens.”

- “How can people in Europe decide on what is needed most in India?”

Heated discussions followed. Some suggested that we should apply for pig sties, but then use the money to build prayer huts in catechumen villages. Others wanted the bishops to complain to the Pope. It was obvious that something was terribly wrong.

On the one hand I understood the general mood in the West which was in favour of giving priority to relieving poverty. On the other hand I was convinced that the aid agencies, if properly advised, would try to help the local church in their genuine needs. So I addressed the meeting making a promise: “If I will be allowed to represent the bishops of Andhra Pradesh, I will talk to the aid agencies and see if something can be organised.”

The other side of the picture

The bishops authorised me to represent them. So in 1968 when I was granted a short home leave during summer holidays at the seminary, I visited the headquarters of various aid agencies. First I went to the Katholische Jungschar in Vienna. I was well received by Mrs Helga Schriffl, who was in charge of the mission department at the time. She was very sympathetic to what I had to say. And she made me understand that the aid agencies had problems of their own. This was confirmed in meetings I had with other aid directors.

The project desks of a typical European office were flooded with applications. The staff responsible for screening and approving them had little factual information to go by. When I visited the offices of MIVA in Breda, the Netherlands, for example, I could see the problem first hand. MIVA dealt with applications related to vehicles for missionaries and development workers. They showed me a list of 15 applications for jeeps and motorbikes by priests in Andhra Pradesh. They asked me: “Can you let us know which of these are the most deserving cases?”

“I can’t”, I said. “Andhra Pradesh is so large that it is impossible to know the situation in all dioceses, even less in each of the 219 parishes with their 3,250 outstations. It is only the local people who would be able to tell you which of these applications is more urgent than others.”

I also found that the sheer volume of the work reduced the time available for evaluation. The project director for India in MISSIO Aachen told me he could allow no more than 20 minutes’ assessment time per application. Skilful writers who presented projects well had a better chance of receiving aid than, perhaps more deserving, local leaders who were only fluent in their own vernacular. Moreover, the European staff would be more inclined to sanction bigger projects which might look more worthwhile than smaller ones which they found it difficult to assess. So one particular parish might be given Rs 100,000 (£6,000) to build an oversized church while the same amount could have been utilised to finance 32 smaller projects:

- 2 one-day instruction camps for 100 persons each,

- 2 motorcycles for parish priests,

- 10 prayer huts for catechumen villages,

- 2 one-year scholarships for children in a village boarding school,

- and grants to 10 catechists of a pushbike, a buffalo and an annual salary each.

Giving birth to the child

It was clear that the solution required more than superficial adjustments. It needed a radical re-think. Not only much of the administration of aid application, also a large share of the decision-making should be in the hands of the local church. But how?

It was while visiting the headquarters of Swiss Catholic Lenten Fund in Luzern, Switzerland, that I began to see new possibilities. What impressed me most of all was the structure of the Swiss setup. They made a clear distinction between three bodies with specific and separate responsibilities. 1. Data gathering about the projects and their administration were handled by the central office. 2. An advisory committee of independent experts met from time to time to decide on principles of priority and to select the specific projects that deserved to be funded. 3. Finally the bishops’ conference retained ultimate responsibility by appointing the officials in the central office and the members of the advisory committee.

I concluded that we should adopt this same model for Andhra Pradesh.

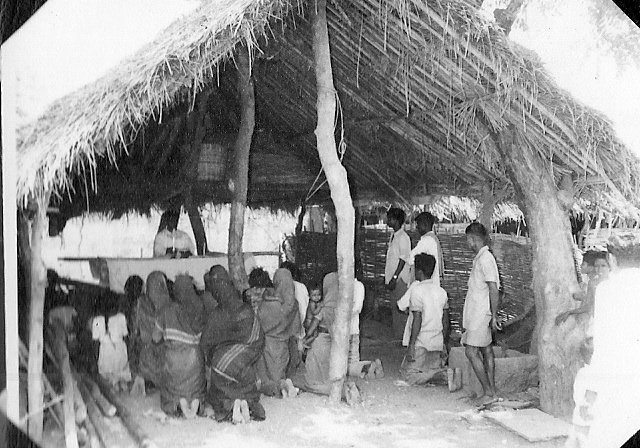

Mass celebrated in an open prayer hut.

The difficulty was not only setting up the actual organization in India but especially to sell this new approach to our bishops who were anxious to keep as much control over their dioceses as they could. Would they accept the decisions of a state-wide advisory committee? And what about the aid agencies? Would they agree to work with the dioceses of Andhra Pradesh in this manner?

Months of negotiations followed. I talked to individual bishops as well as the bishops’ conference in session. I kept in touch with the agencies. A beginning was made by the recruitment of full-time staff to our central office. The bishops appointed the first diocesan delegates to the state-wide advisory committee. A first overall pastoral programme was drawn up with a budget for the whole region. But what would we call the whole venture?

Originally we called it ‘Illuminare’ [= to illuminate]. But then I recalled the advice of Mr G.S. Reddy, a Catholic member of the national parliament. “Our Christian missionaries have made mistakes by giving their institutions western names, such Institute for the Poor, Communication Centre, etc.”, he told me. “We should choose Indian names which resonate naturally in the hearts and minds of our people!”

So I enlisted the help of seminarians, college students, religious sisters, diocesan priests and prominent lay people to search for the right name. Eventually I had a list of more than one hundred possible names. These were scrutinised on their merits.

In the end a good name emerged: Jyotirmai. When the bishops accepted the name, Jyotirmai, the unique partnership between a local church and European aid agencies was born. Jyotirmai is Telugu for “radiant with light”. And light it would shed!

Now we had to get the agencies on board. The five most interested partners proved to be AMA, the mission fund of Dutch religious congregations; the Austrian Der Katholischer Jungschar; MISSIO Aachen and MISSIO Munich in Germany; and Swiss Catholic Lenten Fund. But now a proper agreement needed to be worked out.

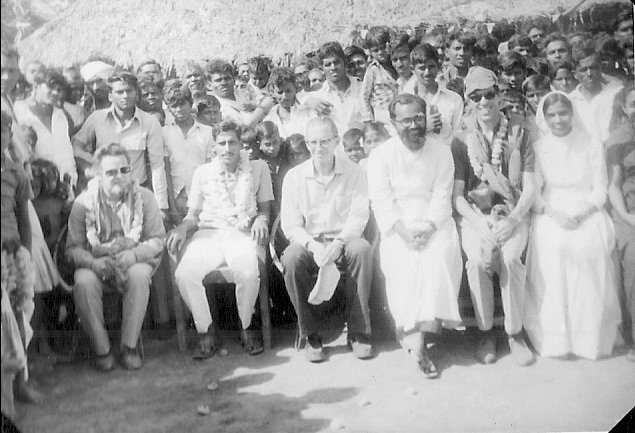

Dr Willi Dober, the village chief, myself, the parish priest and Ferdinand Luthiger at a meeting in a village. 1975.

At my invitation the agencies sent a delegation to Andhra Pradesh: Ferdinand Luthiger of Swiss Lenten Fund and Dr Willi Dober, an expert on business management who was also an advisor to Swiss Lenten Fund. They spent two weeks going round various dioceses to see the parishes in action. Then they met with the state-wide Jyotirmai Advisory Committee and finally with the bishops’ conference.Dr Dober and I drew up an agreement that outlined the principles of the partnership. After discussion it was signed by both parties. Because of its historical significance I print the original text here.

NORMS TO GUIDE THE COOPERATION BETWEEN JYOTIRMAI (ANDHRA PRADESH) and SWISS LENTEN FUND AND MISSIO (GERMANY)

Formulation finalised, 21st January, 1976.

General guidelines

- True cooperation springs from a sense of partnership which fosters a mutual sharing of spiritual and material gifts.

- To serve the genuine development of the Church in Andhra Pradesh and to avoid wastage of resources, aid will be given to the objective priority needs.

- Deciding on what are priority needs and what not, is the task of the Church in Andhra Pradesh which, in making these decisions, will also take into account the experience of Swiss Lenten Fund and Missio Germany.

- It can be foreseen that the Church in Andhra Pradesh, as a rapidly developing Church, will require special help for some years to come. However, all efforts will be geared towards obtaining self-reliance as soon as possible.

- All projects undertaken under Jyotirmai are such as to respect fully the prescriptions of the Church and the laws of the country.

Organizational Structures - The hierarchy of Andhra Pradesh has established a State-wide committee of at least 20 members comprising of bishops, priests, religious and lay people, which has the authority to determine priorities, screen and recommend projects, and allocate funds on its behalf.

- Members to this committee are appointed by the Andhra Pradesh Bishops’ Council, not on a. strictly representative basis but on account of their experience and/or expertise. They have the duty to promote the good of the whole Church in Andhra Pradesh in a spirit of truth and impartiality.

- To execute the day-to-day business of the Jyotirmai committee, to disburse funds allocated and the inspect the progress of the projects, Jyotirmai has at its disposal a full-time and fully authorised project director who has all the facilities required to execute the work.

Procedure of Application - Although every person is free to apply directly to the donor agencies, priority will be given to those projects that have obtained a recommendation from the Jyotirmai committee.

- Local contribution and active involvement in the execution of the project are necessary conditions to receiving aid.

- The Jyotirmai committee presents annually an over-all plan, with a regular budget fixed in consultation with the donor agencies. According to this budget the needs will be met systematically and effectively in the course of time.

- The Jyotirmai committee guarantees that the funds received are spent for· the purpose previously indicated, that they are properly accounted for and recorded in a report.

These principles will be adhered to in the spirit of the Gospel and true Christian fellowship.

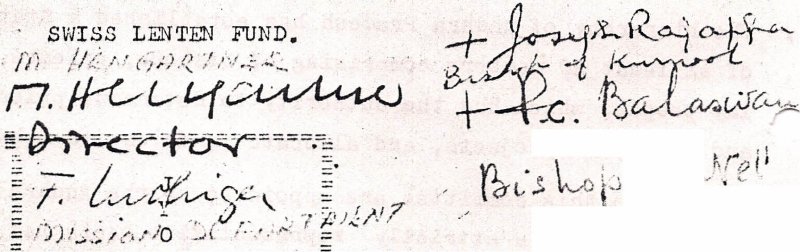

Signed by M. Hengartner, Director, and F. Luthiger, Mission Department, of Swis Lenten Fund on behalf of the donor agencies.

Signed by Chairman Joseph Rajappa, Bishop of Kurnool, and Vice-Chairman P.C. Balaswamy, Bishop of Nellore, on behalf of Jyotirmai.

Seeing the child grow up

Under the new agreement, local applications were no longer submitted to the agencies separately and judged on their own merits. Instead, every year the local needs and priorities of the dioceses were expressed in one overall state-wide pastoral plan. The agencies supported the plan by providing the lion’s share of the required budget.

Though the bishops’ conference retained ultimate responsibility, it had entrusted the tasks of screening and planning to the Jyotirmai committee which consisted of 2 bishops, 15 priests, 9 sisters, 2 brothers and 14 lay people drawn from different dioceses. The committee had true decision-making power. It laid down pastoral priorities. It allocated which portion of the budget should be spent for each type of project. It determined which specific projects could be funded in a particular year and on what conditions. It supervised the execution of the projects for which aid was given. It acted as an economic planning body, a parliament and a ministry of finance all wrapped into one.

After at least 40 years of successful operation, the merits of Jyotirmai have been unmistakable. Its impact has been proved beyond doubt. Large-scale and expensive building programmes were effectively stopped or at least curbed. It was the smaller projects that were favoured. Preference went to training and to helping the ‘underdog’: village communities, one-shirt catechists, children from far-out hamlets who could only receive a good Catholic education in parish headquarters.

The budget for 1982, for example, spent only one third on buildings: four dormitories for village boarding schools, three moderate-size churches, 25 multi-purpose chapels/schools, seven houses for priests, three convents for nuns and 50 thatched-roof prayer huts. The other two-thirds covered 298 instruction camps benefiting 25,000 people, 21 literature programmes, 9 motor cycles, grants to 583 catechists for one-month in-service training, and scholarship grants to 1,305 school children and 400 college students. Without Jyotirmai most of these mini-projects would never have received aid. No agency in the West could have handled the screening required or guided the funds so effectively to village-level beneficiaries.

Mass in a mud-brick prayer hut.

More remarkable still is the process of self-examination which had been set in motion. A great deal of theological reflection and spiritual soul-searching can result from allotting rupees and paise. Some questions originated with the agencies, who wanted to know why village boarding schools were rated so highly? Or why catechists were not given better salaries? Doubts arose from within the projects themselves. To what extent does a church building help to form a community? Should a priest’s house be bigger than that of a village elder? What kind of instruction should be given in catechumen instruction camps? Why do so few people subscribe to the Telugu Catholic weekly? What attracts converts to Christianity? What kind of Church are we supposed to be?

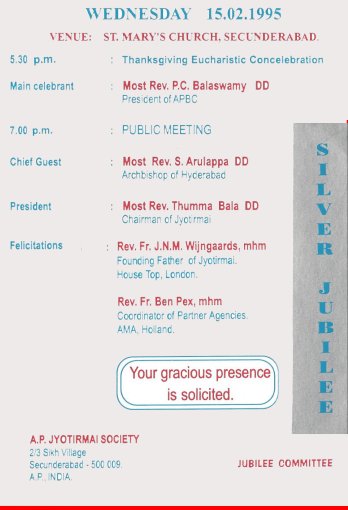

Silver Jubilee celebrations in 1995

All decisions about church finance depend upon a pastoral vision. It took years before this obvious fact was commonly recognised. When it was, Jyotirmai appointed a full-time pastoral director who was to concern himself not with finance but with the pastoral coordination of the projects. Then it commissioned a full-scale research programme, which in its turn called for a programme of renewal and the establishment of a permanent ‘thinking cell’.

Reaching adulthood?

Another benefit of Jyotirmai was that it gave the Catholic community in Andhra Pradesh a new sense of self worth. Mission work is often regarded by Christians as a form of charity, ranking with leprosy work and care of the destitute. Third world churches are treated as dependent, immature minors who need to be spoon fed. Catholic Andhra Pradesh succeeded to free herself from the chains imposed by such paternalism. She was recognised as a true partner in a common task.

Going by reports I fear that in recent years, since 2006?, Jyotirmai has gone through stormy waters. Reasons seem to be manifold. The rate of conversion has slowed down. The needs of the dioceses and parishes have, perhaps, shifted from outstations to local centres. But, in spite of all this, Jyotirmai has continued to flourish. Through the decades it built up thousands of small Catholic communities, provided education and training to its leaders and left a lasting infra-structure. The credit for this success should go to many, many enlightened people who were prepared to try a new form of true partnership and make it work. I am happy to have helped erect this lighthouse that has guided so many ships into the right harbour.

For illustrations of our Jyotirmai yillages, go to: http://www.johnwijngaards.com/galleries/jyotirmai/index.html.

John Wijngaards, My Story – My Thoughts, Part Three. MISSION IN INDIA

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage