My job at Mill Hill

In September 1976 I attended the General Chapter of the Mill Hill Missionary Society in Mill Hill, London. I was there as the elected representative for the Mill Hill members in India. To my surprise and dismay, towards the end of the chapter the delegates elected me to be Vicar General and Director for the Home Regions for the next six years.

The 1976 Chapter. Members of the new General Council: (1) Fr Brendan Sullivan; (2) Fr Louis Purcell; (3) Fr Noel Hanrahan, General; (4) myself; (5) Fr Piet Leliveld.

It was a blow. Remember, I was involved in so many crucial projects in India: St John’s College, Amruthavani, Jyotirmai and Jeevan Jyoti to mention but a few. What was I to do? Should I accept or not? My leaving India at that critical stage would entail setbacks to the institutions I had founded and had helped build up. But then: was there no local leadership that could step in and fill the gap? And did the Society’s international mission work not merit priority support? I have always liked challenges. I saw my election as another great challenge. And if I did not accept, someone else would be pulled out of an important task on the missions . . . So after weighing up the pros and cons, I decided to accept.

In the following chapters I will briefly describe my work and my experiences in the new job.

A look at Mill Hill Society

The Society was founded in 1866 by a Welsh priest who would later become Cardinal Vaughan, archbishop of Westminster diocese. Vaughan correctly saw that, with Britain having such a strong colonial grip on a large proportion of Asia and Africa, it would be very helpful to have English-speaking Catholic missionaries. They could supplement the work already being done by French, Italian and Spanish missionaries, men who often endured opposition from English officials. The problem was that England itself at the time had few priestly vocations. Its Catholic population depended greatly on priests imported from Ireland.

Vaughan went over to the continent to recruit new members. He was successful in Tyrol, both Tyrol in Austria and North Italy, but he found the greatest response in the Netherlands. The Catholic Church in Holland was emerging from centuries of persecution and repression. With the Netherlands too being a colonial power, awareness of Third World needs abounded. Learning English posed no obstacle. The end result was that the Dutch joined in droves. They have, from the beginning, formed the vast majority of the Society’s membership. And, together with the English, they gave Mill Hill Society its characteristic stamp of efficiency. It produced no-nonsense present-day apostles, down-to-earth, totally committed, hand on the plough till the bitter end.

The collection of Mill Hill legends contains a revealing story. The Dutch were used to smoke. When the first batch of Dutch students discovered that smoking was forbidden by rule in Mill Hill College, they staged a protest. They confronted the Rector, Vaughan himself, with a challenge.

“Why is smoking forbidden? Does smoking stop you from being a good missionary?”

Vaughan reflected. The students were right. Mill Hill College was not aiming at producing religious men under vows. Its training focused on forming efficient missionaries. Smoking should not be a problem. So he said: “You have a point. Smoking will be allowed.”

The students persisted.

“Does this apply only to us, or also to our posteriors?” They meant: to future generations of students and members?

Vaughan smiled.

“Yes, also to your posteriors!”

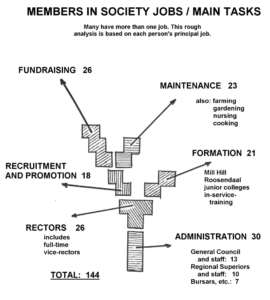

Between 1976 and 1982 the Society was still a formidable force. When my term of office terminated, it still counted 956 members. The largest number, 550, worked in mission territories, spread over 37 dioceses in 16 countries of Africa, Asia and Latin America. 451 members resided in our five home regions: Britain, the Netherlands, Ireland, North America and North-plus-South Tyrol. Among this last group, 153 lived in our 6 retirement homes, 144 did society work at home, 143 were ‘Non-Residents’ [= members not living in Mill Hill houses]. These were missionaries who had returned from the missions and were now engaged in parishes or chaplaincies.

My initiation experience

I had hardly taken up the job, when I was suddenly confronted with my first real challenge.

The Rector of our retirement home in Freshfield rang to say that Bishop Billington had died. He asked the Superior General to come and be the main celebrant for Billington’s funeral mass a few days later. Billington had been Bishop of our diocese of Jinja in Uganda, and because of his status in the Society it seemed appropriate that a top-ranking Millhiller preside at his funeral.

At the last minute Fr Hanrahan could not go, so he delegated me to take his place. I took an early train up to Liverpool, then to Formby and arrived in Freshfield just in time for mass to begin. I felt under quite some pressure because I had not been to the house before. Rector, staff and residents, all Mill Hill men were new to me. So handshakes all around.

I went to the sacristy. As I was putting on the celebrant’s vestments, the door suddenly flung open and Archbishop Derek Worlock of Liverpool stepped in.

“I heard about Billington’s funeral this morning”, he said. “I will be the main celebrant.”

“Great!”, I said, with some genuine relief.

I concelebrated with the bishop. After mass I accompanied the bishop in the procession to the cemetery. And after the whole service, I stayed with the bishop as we were invited into the members’ lounge for a cup of coffee. While shaking hands with others I came across, I stayed with Worlock as much as possible and chatted with him. It was my responsibility, I felt, as the principal Mill Hill representative.

So far so good.

After a short while, the archbishop looked at his watch. “I have to go”, he said. He signaled to his secretary that time was up. Both men made ready to go, taking leave of the rector and other Freshfield staff.

I stayed with the archbishop as he was leaving the lounge and I conducted him through a lengthy corridor to what I thought was the main entrance. There I said goodbye myself and opened the door for him.

The archbishop walked in – then, almost immediately, with a red face, walked out again.

It turned out that I had conducted the archbishop into a toilet, instead of making him leave through the main door!

Shock horror!

Some of the retired men saw the incident and laughed – which, I fear, Worlock may have seen . . . Anyway, I laughed myself, afterwards. At that moment it was a great embarrassment I assure you, a somewhat unusual conclusion of my first official function as Vicar General.

The annual routine

As personnel manager of the 451 members in our home regions it was my task to meet as many of them as possible every year. This meant, first of all, visiting all the society houses, of which there were 24 at the time. For instance, there were 5 houses in the British Region: Mill Hill itself, Freshfield near Liverpool, Burn Hall near Durham, Courtfield on the border with Wales, and our house in Glasgow.

I would meet each person living in the house, then have meetings with the various teams working in the house to review their progress. Meanwhile non-resident Millhillers working in neighbouring parishes would be also be invited to come and meet me in that house. I would visit some non-residents in their own places. I would keep a detailed record of all these meetings. Finally I would have a concluding meeting with the regional council in the region – to evaluate my findings and see what action should be taken.

Four times a year the General Council would meet. I would submit a full written report to them of my meetings during the preceding three months, outlining the situation in each of the houses I had visited and the needs of individual members. Other council members would do the same with reports about Africa, Asia, and so on. This often led to personnel changes as I will explain later.

As you will have guessed, my job entailed a lot of travel. Journeys did not always go smoothly. I remember the first time I flew in from the UK to Kennedy airport at New York in the USA. My flight was delayed and on arrival I found there was no one to meet me. I decided to phone our house in Yonkers, but it was well after midnight. I discovered that I needed American dimes to operate the public phone system. I possessed no USA coins. Exchange offices were closed. I then persuaded a fellow traveler to give me a few dimes. I spoke to the Rector at Yonkers, an Irishman. He was not pleased to hear from me so late at night. He told me to catch a commuter bus to a meeting point in the Yonkers area where he would pick me up . . .

On another occasion, the Tyrolese regional, Fr Henry Palhuber, was going to give me and 70-year old Fr Anton Schmidt, a German Millhiller, a lift to Innsbruck. We had been attending a meeting with retired members somewhere in Vorarlberg. It was snowing heavily. Henry had put snow chains on his tyres. But as we wound up a treacherously slippery mountain road, Henry heard on the local news that an avalanche had blocked the road to Innsbruck.

“Wait!”, he said. “There is a station not far from here. You can catch a train to Cologne.”

As we entered the station dragging our luggage, an international train roared in and stopped.

“Quickly! Get in!”, Palhuber shouted.

We climbed in without having got tickets first. Almost immediately the train pulled out of the station . . . We thought we had made it, but a ticket collector came by and told us we were on an intercity to Vienna. The wrong direction! “Fortunately for you”, he said, “because of the snow, the train is making an emergency stop in five minutes’ time. You can catch a train to Cologne from there.”

The train did stop after five minutes. We got out – and found ourselves in a tiny station. Snow still drifting down around us. No one to be seen anywhere. And when we finally located the station master in his dingy office, he told us very few trains stopped there. “The next train in the direction of Germany leaves after eight hours.”

We found a small Gasthaus in front of the station. Sitting close to the wood-fire hearth we ordered Sauerkraut and beer.

To pass the time I asked Anton to tell me about his pioneering work in the interior of the Cameroons. Most villages he visited, he told me, had never seen a European. And they applied for baptism in droves . . .

“Why were they so keen on Christianity?”, I prodded.

“Well”, he said. “That was mainly because of the women. They were badly treated by their men.”

And then he told me a story which, to this day, I still don’t know whether it was fact or fiction.

“In those villages”, he said, “people were still cannibals. When grandmother or mother became too old to do useful work, the family would decide it was time for her to go. But they would not eat her themselves. They would go to a neighbouring village and trade her in exchange for one of their mothers or grandmothers. But they had one pious custom . . .”

“What was that?”, I asked.

“After the meal, they would save the woman’s knuckles and send them back to her original family. The family would keep these as a remembrance.”

I laughed. But Anton swore that he was telling the truth.

“Believe me! That’s what happened. People told me themselves. They showed me the knuckles”, he said.

Personnel manager

In Mill Hill Society all major appointments were made centrally, that is: through the General Council. Our quarterly session gave a chance to each of us to report on our findings during visits to mission areas and home regions. Because of the needs that had emerged and taking into consideration our discussions with individual members and local councils, proposals could begin to be formulated on the transfer of personnel from one occupation to another.

Each transfer required a long and complex procedure.

The process would normally start with a local team (1) reporting a vacancy and submitting a job description and profile of the person needed to do the job. (2) The regional and his council would draw up a list of possible candidates. (3) The suitability and availability of such candidates was then assessed by the General Council. (4) This might lead to the proposal of a new appointment. (5) This would be followed up by more consultations. If a member was withdrawn from a mission territory (say the Sudan) to a home region (say Scotland) for a specific task (recruitment), the local bishop in the diocese, the local regional council, colleagues of the individual and the individual himself would be involved. The General Council would guide this process, assess confidential information not known to others and take the final decision.

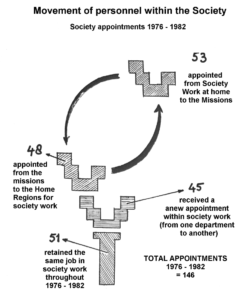

The scale of the operation was huge. To give you an idea, during my term of office (1976 – 1982), the General Council made 146 major appointments:

- 53 members were appointed from society work in the home regions to tasks in the missions.

- 48 members were appointed from positions in the missions to work at home.

- 45 members in the home regions were appointed from one task (e.g. teaching in a minor seminary) to another (e.g. fundraising).

As Vicar General and Director of the Home Regions I often played a central role in such appointments. I was well aware that my own judgment and decision in the matter could have life-changing consequences for the particular member in question. I have some distressing memories. Take the case of Father Hans Hienkens MHM.

Hans had had a short but successful career in the Philippines. He had been the first President of St. Anthony’s College in San José on the island of Antique. When I visited the USA, I found that he was acting as one of the local Mill Hill organisers in Los Angeles. His job consisted mainly in collecting the contents of mission boxes and, occasionally, preaching on mission. He also helped out in a local parish. Now Hans had a brilliant mind and my honest assessment was that his talents were seriously underused. He was wasted in the job that had been assigned to him.

In 1980 Mill Hill Society was requested to provide a staff member to the German organization Missio. Missio in Aachen was the agency that distributed millions of dollars from German dioceses to missionary projects all over the world. I knew Missio intimately since I had often presented Indian projects to them. The Director of Missio requested Mill Hill to provide a missionary who could head their Asian section. Since many of our mission territories benefited from Missio grants every year, it seemed right and just to help them.

Hans Hienkens fitted the bill. He had personal experience of the Philippines. He possessed an excellent sense of judgment. He spoke both German and English fluently. He was more than capable to fulfil the task: heading the Asian administration at Missio, interviewing mission bishops and other missionary personnel visiting Aachen, maintaining a steady flow of correspondence and formulating priorities for Missio’s grants.

When I spoke to Hans about this, he was in two minds about the appointment. On the one hand, he welcomed the challenge. He acknowledged he was underemployed in Los Angeles. On the other hand, he had created a circle of personal friends in Los Angeles and had enjoyed their luxurious style of living when staying in their houses. But his main concern, he told me, was his diabetics.

“I suffer from a pernicious kind of diabetics”, he said. “My American doctors have worked out a mix of medicines that keeps me alive. They have me under observation.”

“Well”, I replied. “You are right to be concerned. But surely, those medicines are also available in Germany. And among German doctors there will be specialists too.”

He hesitated, but finally agreed.

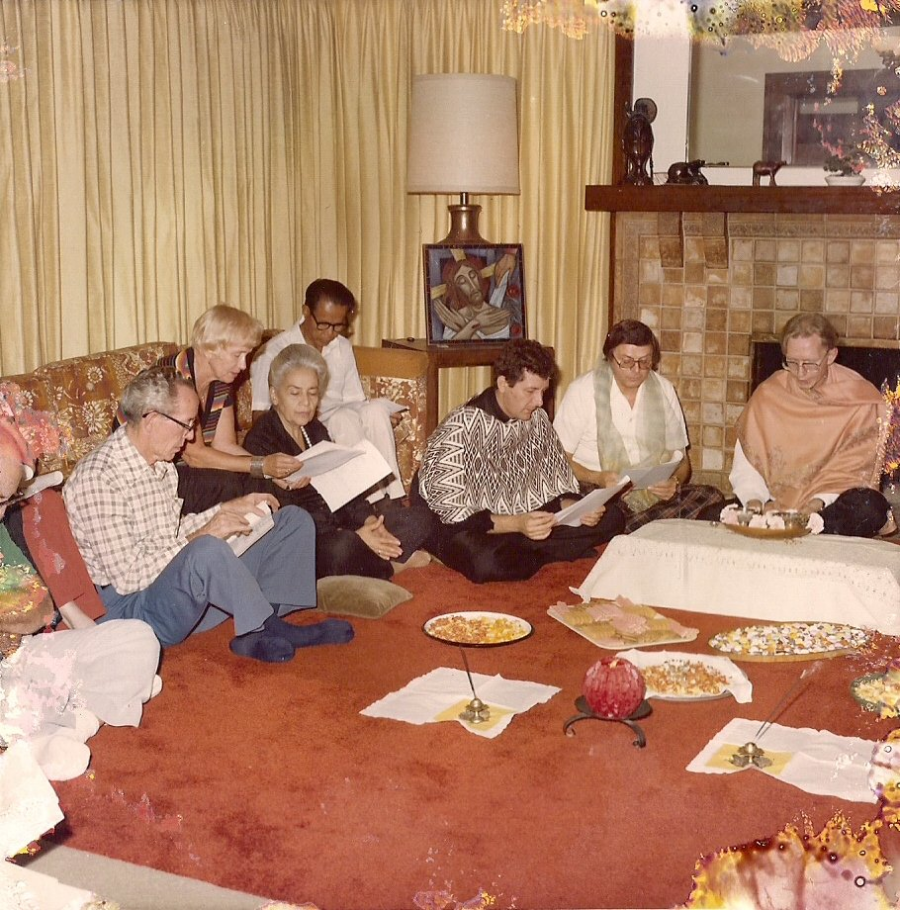

Saying an Indian Mass for our members and friends in Los Angeles. Hans Hienkens first on my right.

Hans Hienkens was inaugurated in his new task just after Christmas 1980. Then, hardly two weeks later, on the 15th of January 1981, the shock: he suffered a massive diabetic attack — and died. It happened in the evening in his Aachen apartment. Apparently, he collapsed just after speaking on the phone to friends in Los Angeles. He was still using the medication he had brought from the USA. Nobody knows why at that moment he could not give himself the injection that would have saved his life . . .

His death hit me.

Was I to blame?

Would he still be alive if I had not moved him from Los Angeles?

On reflection I decided to just accept the fact. I had done my best when making the appointment. I had been convinced that the arrangement would both do justice to Hans and serve the best interests of the Society and its missionary work.

My agenda

Half way through my term of office, in 1979 at an Assembly of key Society leaders, I laid down 17 principles which, I felt, expressed what I was trying to achieve. I explained the meaning and full extent of these principles in a lengthy document (Documents of the Society Assembly 1979, Mill Hill, pp. 41-65). I will list them here because they show the complexity of the job.

“My objectives are:

- To maintain the essential services of the Society in spite of dwindling personnel resources.

- To achieve a healthy flow between missions and home regions to re-deploy our younger men in Society jobs.

- To respect the needs and charisms of the individual member.

- To base important decisions on research and study.

- To evaluate the validity and viability of every Society house in the Home Regions.

- To preserve our international character while respecting the uniqueness of each country.

- To delegate to the Regional & his Council as much authority as possible within the constraints laid down by the 1970 and 1976 Chapters.

- To make the Society join other missionary Societies and missionary organizations of the Home Church in common projects.

- To make the Society participate in the process of communication that goes on within the Church and within society at large.

- To maintain an active and realistic recruitment programme in all five Regions.

- To promote a priestly formation programme suited to the requirements of our times and the needs of our missions.

- To clarify and guide the growth of our mission-animation centres.

- To provide useful services to our members of the missions and to the missionary Church in general.

- To strengthen internal communication within the Society at all levels.

- To offer our retired members years of happy and meaningful rest after their labours.

- To give full recognition to the contribution which our ‘non-resident’ members give to the Home Church.

- To animate, encourage and support our members in their missionary vocation.”

Read also: The Society in the Home Regions.

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage