I will not bore you with a long tale of how I had to gradually discover the full extent of human sexuality. When on home leave in the Netherlands I bought porn magazines to see naked girls. I watched some x-rated movies. In Hyderabad I acquired a full length mirror and got used to see myself naked. I read the Indian treatise on love making, the Kama Sutra, with considerable interest. I was making up for a learning process I should have had as a teenager.

During the final years leading up to my priestly ordination I had been made to promise celibacy for the rest of my life. Because it was a promise to God, it was called a ‘vow’. I had willingly accepted this obligation because it was a legal requirement if you wanted to become a priest. Church Law prescribed it. I began to realize that my promise might have been invalid. My ignorance about women, sex, intercourse and marriage invalidated my commitment.

Classic moral theology teaches that a promise, even if made under oath, ceases to be valid by ignorance or erroneous knowledge. This applies to errors affecting the content of the promise or the purpose of the promise. A marriage vow by a woman who does not know anything about intercourse, for instance, is invalid. A promise to donate money to a leprosy hospital is null and void if the hospital actually does not materialise. Thomas Aquinas says that such promises or vows collapse. They fold up ‘from within’. They have no substance. They are hollow, empty, non-existent and non-binding.[i]

It gradually dawned on me that that was the situation I was in.

In February 1975 I went through an extremely busy period. Work loads oppressed me from every side. They almost killed me. I had a full-time lecturing job in St John’s College at Ramanthapur. I carried all the responsibilities of being Planning Director of Amruthavani Communication Centre in Secunderabad, with 60+ staff members dependent on me. I was a member of the National Council of the All India Bishops’ Conference and of Theological Publications in India. I gave regular part-time courses at the National Biblical Catechetical and Liturgical Centre in Bangalore. I was completing some new publications . . .

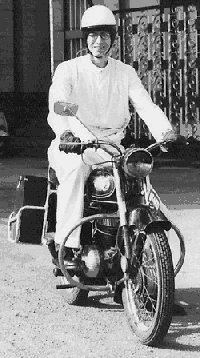

Me on my motorbike in front of the Seminary

When I said it almost killed me, I was not exaggerating. I realised this when travelling on my Jawa 250 motorbike from St John’s College to Amruthavani. Indian roads were narrow and chaotic at the time. I had to manoeuvre my way through buses, lorries, water buffaloes, children running across the road without warning while trying to avoid deep holes in the tarmac left by the previous rainy season. Fatal road accidents frequently occurred. Well on that day, just before the major road junction at Târnâka I experienced a moment of mental oblivion. My mind went blank. I did not know where I was. My vision was blurred. I felt utterly confused.

I was still able to stop the motorbike and push it to the side of road. I staggered to a tea stall that happened to be close and sat down on a stool. Holding a fresh mug of tea in my hands I felt my mind clearing.

I realised the importance of what had happened. It was a warning sign. It would be suicide to ignore it. Survival mattered more than pushing on, regardless. I knew I needed a good break.

So when I had recovered a little, I turned the motorbike round and returned to St John’s College. I went to see Father Fred Moss, the acting rector at the time, and told him what had happened.

“Enough is enough”, he said. “You’re overdoing things. Cancel all your lectures and other commitments. Take two weeks off.”

I followed his advice. Next day I flew from Hyderabad to Chennai, which was then called Madras. In Madras I dropped into a tourist office and they advised me to book in at a beach resort Mahabalipuram, just south of town. I went there the same afternoon, finding accommodation in a small tourist lodge.

Mahabalipuram is blessed with wonderful white sandy beaches lined with palm trees stretching along the coast both north and south. There were very few tourists at the time. It was truly a paradise. I loved walking along the sea and taking an occasional dip in spite of the high coastal waves. The only people I met were the occasional Tamil fishermen hauling in a net or other guests in the lodge. I suddenly had time to rest, and sleep, and think . . .

After a few days I began to put my thoughts down. I took decisions about my work. But I also reflected on my sexuality. Here is one of the entries in the ‘self definition’ I drew up at the time:

“I never want to forget that I am also ‘body’. I accept my body in its fulness; with all its limitations, its feelings, its possibilities. I reject the inadequate spirituality of my early years in which there was no healthy place for sex. I see sex as a beautiful gift from God to me. I realise there can be no question of sin in sex unless I harm myself or others through what I do.”

Love and intimacy

Mahabalipuram beach, the tourist lodge on the left

There were other guests staying at the tourist lodge. I was the only single person and the only European. All the others were Indian couples. But not all was kosher as I soon found out while eating a delicious Tamil thâli: a wide round plate with boiled rice heaped in the middle with vegetables, curries and chutneys arrayed around it.

“Many of them are businessmen bringing their mistresses from Madras”, a friendly waiter whispered to me.

I could easily see who they were: middle-aged men in smart suits with young girls in colourful saris. But there was a happy, married couple too. They had two small children. Husband and wife obviously were in love with each other. They looked at each other’s faces, chatted and laughed.

I felt a pang of envy. Their closeness was something I missed . . . I was paying the price of being celibate. What was the cost?

Was I doomed to a life of loneliness? Would I be forever deprived of intimacy? I had been privileged in the past because I had enjoyed close emotional intimacy. One had been with my mother when I was rather young and sharing with her and my brothers constant hunger, dysentery and humiliation during four long years in the Japanese POW camp. The other had been with my older brother Carel. With him I had been able to share all my secrets: my fears, hopes, daily adventures, plans for the future, my latest dream . . . He had died while in college.

The dread of loneliness fell all the more on me through a near-death experience.

I had been walking along the sea in Mahabalipuram early in the morning, admiring the waves splashing in from the ocean at regular intervals. The sun stood not yet too high. Seagulls skilfully sailed through the steady breeze. Nobody else was on the beach except for a single Tamil fisherman and some nervous crabs digging themselves into the sand.

I am a keen swimmer and I had reached a small bay. The water looked tempting. It was soothingly warm. I walked in and was about to swim out into the deep when the fisherman dropped his line and came running up to me. His gestures were unmistakable. He frantically waved to make me come back. I went back onshore, unsure of what was wrong. The fisherman did not understand my Telugu, but he explained his reason by what he did next. He cut a piece of wood from a dead palm tree branch and threw it into the water. The wood circled on the water for just a few seconds, then was sucked under and swept out forty yards into the sea. I had been on the point of swimming straight into a dangerous undersea current!

I thanked the fisherman. Later in the lodge I heard that a Scotsman had drowned in more or less the same location a year earlier. I had been lucky to escape the same fate. Out in those coastal waters there is no one who can pull you out. I had almost died but there was no one with whom I could share my feelings of delayed shock and intense relief.

It gave me much food for thought. Here I was, far away in a foreign country, with many responsibilities on my shoulders. I worked from early morning to late at night. I had dreams of building up some important new structures for the Church in Andhra Pradesh. I endured pressures from colleagues, students, staff at Amruthavani, distrustful bishops and angry critics. I was creatively involved in developing new correspondence courses for Hindu inquirers, new Christian films, radio programs and spiritual books, as I will explain later. But in all this I was deprived of the possibility of sharing my hopes and fears on a deep personal level.

Is God a rival?

Traditional teaching on celibacy stressed that a priest should choose between God and a human partner. They would quote St Paul’s words:

“I would like to see you free from all worry. An unmarried man can devote himself to the Lord’s affairs, all he needs worry about is pleasing the Lord. But he married man has to devote himself to the world’s affairs and devote himself to pleasing his wife: he is torn in two ways.”[ii]

Now I realized that there is truth in that. Not being married gave me more freedom and flexibility in some of my missionary apostolate. I could see this in the restraints put on Anglican missionaries I knew who were married. Their wives might develop special health problems. They had to find suitable schools and colleges for their children – which might be challenging if they were stationed in rural parishes. But the reverse was also true.

I got acquainted with a Methodist couple in Secunderabad who were top-class missionaries, each in their own right. And whenever I visited them I was struck by the support they could give each other. They would discuss plans together. If anything went wrong, they went through a shared process of honest analysis, searching prayer, healing and emotional repair. And it did not in the least stand in the way of their relationship to God. In fact, I recognized that God was in each of them, sustaining, comforting and loving each other.

One of my priest colleagues in St John’s College whom I shall call Phil, a warm-blooded enthusiast from Manchester, fell in love with an American girl. Phil was teaching Catholic theology. She worked in a Pentecostal parish in Bombay. When they got married, I went out of my way to call on them at their home in a neighborhood of slums. Looking after the down and outs was their mission. They were both intensely happy. Again I found a deep level of sharing: shouldering joint responsibilities for people and carrying each other in their commitment to God’s love.

Married couples do not always enjoy the fruitful and life giving intimacy that should be theirs. But where it was present, I reflected, it surely was a gift from God: God revealing himself as love in and through the loving partner. In a truly Christian marriage God was not a rival for each partner. God became more intensely present and real in the profound affirmation of self worth imparted by genuine deep sharing and intimacy. Augustine’s brash principle: “Celibacy is a more perfect state of life than marriage”, was as much a fallacy as his other teachings on sex.

As I stated before, I had come to realise that the promise of celibacy I had made before ordination did not really bind me. It had, somehow, been forced upon me. On the other hand, I did not want to upset the crucial priestly tasks I was engaged in. My commitment to priestly and missionary service should take priority I felt. So while acknowledging my right to marry, I decided I should abstain from marriage or physical relationships with women because of the actual situation I was in.

At the same time I also affirmed my personal appreciation of marriage and my right to be married if I were to come across the right person and circumstances would change.

This is what I noted down in Mahabalipuram:

“God has made me a man. He gave me the physical and psychological make-up that enables me to give and receive life-long and intimate love. Whether I actually marry or not, depends on circumstances and my free choice. But at all times I want to be the kind of person who can or could sustain such a generous and mutually liberating partnership. Meanwhile my basic vocation to love will make me give all women the respect and affection they deserve.”

[i] Thomas Aquinas, Scriptum super IV libros Sententiarum dist. 38, q.1, sol. 1 ad 1; D. M. Prümmer, Manuale Theologiae Moralis, Freiburg 1936, vol. II, ‘De Voto’, pp. 326-348.

[ii] 1 Corinthians 7,32-33.

John Wijngaards, My Story – My Thoughts, Finding God in a partner?

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage