In this chapter I want to give a brief characterization of my father, Nicolaas Carel Heinrich Wijngaards. He died thirty years after the war: in 1978. But I feel this is the right place in my story to give him credit for who he was. I owe a lot to him. Not only do I carry 50 per cent of his genes, he helped me realise the potential that was in me. He was a model I consciously and unconsciously have strived to live up to. I am proud of him.

Teaching

My father was first and foremost an educator. After the war he held the position of lecturer at the Teachers’ Training College in Utrecht, then in Nijmegen. In 1957 he obtained the doctorate in Dutch Literature at Radboud University Nijmegen. He featured prominently in the ‘Nederlandse Leergangen’, a national institute that offered teachers the facility to obtain the MA-level degree in Dutch Literature. For many years he was the chairman of its exam commission for the whole of the Netherlands.

My father was a gifted man. This is already apparent from the ease with which he mastered languages. Arabic was a hobby. He read Italian books in his spare time. As a soldier in the Second World War in the Far East he was commissioned to act as interpreter for the Japanese occupier. In a short time he learned enough Japanese to do the job notwithstanding the very primitive means at his disposal. After the war back in the Netherlands my father created a course in Malay: Malay was one of the languages in which he had qualified while teaching in Indonesia before the war. He also produced six reading books in English for high school students. These booklets used only a limited vocabulary: they were based on the thousand most common words in spoken English. But it was the study of Dutch that would claim the lion’s share of his scientific work.

My father was a gifted man. This is already apparent from the ease with which he mastered languages. Arabic was a hobby. He read Italian books in his spare time. As a soldier in the Second World War in the Far East he was commissioned to act as interpreter for the Japanese occupier. In a short time he learned enough Japanese to do the job notwithstanding the very primitive means at his disposal. After the war back in the Netherlands my father created a course in Malay: Malay was one of the languages in which he had qualified while teaching in Indonesia before the war. He also produced six reading books in English for high school students. These booklets used only a limited vocabulary: they were based on the thousand most common words in spoken English. But it was the study of Dutch that would claim the lion’s share of his scientific work.

To academics in the Netherlands my father is known for his articles on medieval literature. His 1957 publication on the seventeenth-century nun Mechteldis van Lom revealed a poet unknown till that time. Similarly, his 1964 book on Jan Harmens Krul (1601-1646) elucidated the life of a Catholic playwright mainly known through a portrait of him by Rembandt. My father loved real scientific research: collecting material from libraries and archives, deciphering manuscripts, reconstructing a writer and his world. Until just before he died he was working under a grant from the national academic research agency ZWO on a study of the life and work of Jacob Duym (1547-1612). He re-published – with commentary – on texts of 17th-century stage scripts, such as ‘Boereklucht van Teeuwis de boer’ (Stageplay on farmer Teeuwis), ‘Cornelius van Engelen’, ‘De torenbouw van het vlek Brikkekiks’ (Comedy playlet on the tower built in the hamlet of Brikkekiks), ‘Het moordadich stuck van Balthasar Gerards’ (Drama on Gerards, the assassin of William of Orange) and ‘Palamedes’ (Romance of the Saracen Round Table Knight and Iseult).

Many know my father because of the many useful learning tools that he created with others: handbooks such as ‘De Struktuur van het Nederlands’ (Structure of the Dutch Language), ‘Letterkundig Kontakt’ (Familiarity with Literature) and ‘Letterkundige Bloemlezing’ (Literary Anthology). As an editorial member of the Classical Literary Pantheon, he helped plan and expand the series. He was also known for the revolutionary new method of learning the mother tongue that he helped design and which he brought to practical application in the teachers’ training programme of the University of Nijmegen.

Students loved my father. He was a born teacher. His pupils appreciated especially his clear way of presenting what was at stake, his imperturbable good mood, his mild mockery, his interest in real life. He never lost himself in purely academic talk. He always wanted to penetrate the core of existence, eternal values, the actual worth of being human.

In l956 he wrote: “When dealing with literature, the main attention should not be devoted to didactic or formal qualities, however important they may be. . . It should aim at kindling and keeping alive a natural interest in the life, feeling, thinking and acting of other people. . . ”

Elsewhere he says: “I can never forget that behind every single literary product the figure of a person looms up, of a brother or sister in the flesh, maybe dimmed by centuries of time and separated by great distances in space from us, but a real human being all the same.”

So, true to his philosophy of life, rather than just elaborate on his professional work, I want to commemorate my father as a person.

Creativity

Try to survive, like Don Quichote!

In all situations of life, my father showed originality. I have already demonstrated this in his career as a writer. During his awful years of Japanese captivity in Thailand, he escaped deprivation and even death a number of times by adopting new strategies. As Japanese interpreter for his Dutch regiment involved in building a section of the infamous railway, he often had to intervene between the guards and his colleagues. He persuaded the Japanese commander to allow him, accompanied by a Japanese guard, to buy food from neighbouring Thai villages since official supplies frequently came late. When building of the railway came to an end, he was put on the construction of a large hospital. Constantly weakened by repeated malaria attacks, he escaped the back-breaking work under the tropical sun by volunteering to help out in the canteen . .

My father had great interest in art. He himself painted over forty larger and smaller paintings of interest. Between the fifties and sixties, he worked hard for the integration of real art education into junior and secondary schools. With his characteristic will not to leave it at words) he turned his vision into practical publications. He collaborated on school books such as ‘Beknopt Leerboek der Bijzondere Didaktiek’ (Brief Textbook of Special Didactics). He gave a course on ‘Didaktiek van de Kunstwaardering’ (The Didactics of Art Appreciation) and wrote a three-volume book on ‘Kunst, Kunstenaars en Kunstwaardering’ (Art, Artists and Art Appreciation) that would see many reprints.

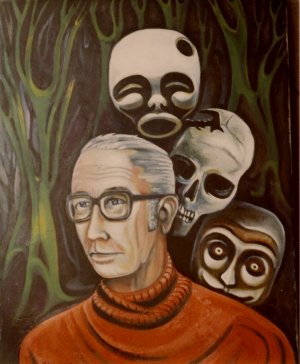

To understand my father, we must especially look at his paintings that express his vision of himself and the world. My father’s images always dance with movement and dynamism. Mystery lurks everywhere, humor pokes his head round the corner. Looking at his self-portrait of 1973, we should notice the strong-minded, almost fierce, expression on his face. Behind him are three figures that preoccupy him. The smirking oriental mask stands for the mystery of life, the great unknown in our existence, the perpetual question ‘why?’. The skull with the gaping wound on its forehead embodies the threat of death, the inevitable calamity no one can escape. The grinning mask of the clown represents the joke of it all, the funny side of life, comedy in the midst of all the tragedy.

To understand my father, we must especially look at his paintings that express his vision of himself and the world. My father’s images always dance with movement and dynamism. Mystery lurks everywhere, humor pokes his head round the corner. Looking at his self-portrait of 1973, we should notice the strong-minded, almost fierce, expression on his face. Behind him are three figures that preoccupy him. The smirking oriental mask stands for the mystery of life, the great unknown in our existence, the perpetual question ‘why?’. The skull with the gaping wound on its forehead embodies the threat of death, the inevitable calamity no one can escape. The grinning mask of the clown represents the joke of it all, the funny side of life, comedy in the midst of all the tragedy.

We can find my father’s self-characterization in other personalities he painted: the ever-moving, ever-searching Ahasverus, the playful and flute-playing rat catcher of Hamelin, the in-deep-meditation-absorbed Eastern monk.

Green, in many scales, was his favorite color. A frequent motif forms the fantastic, winding, almost human trees that dance with a zest for life. During his early years in Indonesia my father had frequently trekked across the wooded mountain slopes of Central Java. Then, when in Thailand, he had encountered the hazards of tangled jungles, their menace to life. For all their beauty, trees and plants in the forest fight each other for survival. In this painting they writhe with pleasure, with the will to grow and flourish. They also growl at each other.

Green, in many scales, was his favorite color. A frequent motif forms the fantastic, winding, almost human trees that dance with a zest for life. During his early years in Indonesia my father had frequently trekked across the wooded mountain slopes of Central Java. Then, when in Thailand, he had encountered the hazards of tangled jungles, their menace to life. For all their beauty, trees and plants in the forest fight each other for survival. In this painting they writhe with pleasure, with the will to grow and flourish. They also growl at each other.

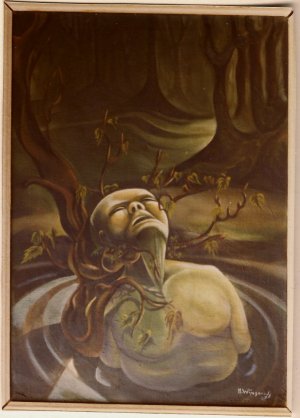

All of my father’s paintings reveal deeper layers of meaning. In this dark scene, painted in 1948 just three years after the war, my father reflected on what he had seen in the swampy surroundings of his camp in Thailand. He recorded the place as having been Me Nam Kwa Noi. He saw the corpse of a Chinese man, probably one of the many who, next to the prisoners of war, were toiling on the infamous railway as forced labour. Reputedly a hundred thousand of such Chinese and Malaysian forced labourers died during the construction, most just thrown into the river without burial. The site looks intimidating and hostile. And yet: light falls on the man’s face. Fresh green sprouts spring up around his body, probably feeding on the man’s putrefying flesh. My father’s thought probably was: “One creature’s death means life for another”.

All of my father’s paintings reveal deeper layers of meaning. In this dark scene, painted in 1948 just three years after the war, my father reflected on what he had seen in the swampy surroundings of his camp in Thailand. He recorded the place as having been Me Nam Kwa Noi. He saw the corpse of a Chinese man, probably one of the many who, next to the prisoners of war, were toiling on the infamous railway as forced labour. Reputedly a hundred thousand of such Chinese and Malaysian forced labourers died during the construction, most just thrown into the river without burial. The site looks intimidating and hostile. And yet: light falls on the man’s face. Fresh green sprouts spring up around his body, probably feeding on the man’s putrefying flesh. My father’s thought probably was: “One creature’s death means life for another”.

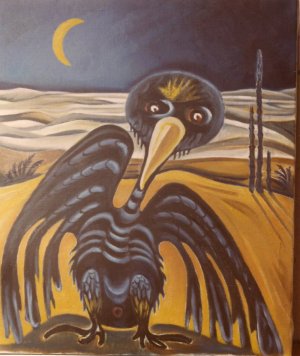

This kind of exploratory thought is also apparent in the 1974 painting of the vulture. Now vultures are common in Thailand, to mention that country once more. I myself remember from my short stay there how just half an hour after I saw a dog dying of rabies, twelve vultures had appeared from the sky as from nowhere and were crawling over the carcass squabbling with each other. They looked ugly, their long scruffy necks covered in blood as they buried their heads into the dog’s entrails. My father’s thought: “What must it be like to be a vulture?” The painting gives us a vulture’s view of life. Nature glows with promise in this moonlit dune landscape. The vulture considers itself good-looking and attractive. And why not? It can’t help being a vulture. Moreover, in some way each one of us is a vulture. We too live on the carcasses of other living beings . . . My father called the painting ‘Tragicomicus’.

This kind of exploratory thought is also apparent in the 1974 painting of the vulture. Now vultures are common in Thailand, to mention that country once more. I myself remember from my short stay there how just half an hour after I saw a dog dying of rabies, twelve vultures had appeared from the sky as from nowhere and were crawling over the carcass squabbling with each other. They looked ugly, their long scruffy necks covered in blood as they buried their heads into the dog’s entrails. My father’s thought: “What must it be like to be a vulture?” The painting gives us a vulture’s view of life. Nature glows with promise in this moonlit dune landscape. The vulture considers itself good-looking and attractive. And why not? It can’t help being a vulture. Moreover, in some way each one of us is a vulture. We too live on the carcasses of other living beings . . . My father called the painting ‘Tragicomicus’.

The meaning of life

I have put a lot of emphasis on my father’s gifts and external achievements. That does not do full justice to him. For he was above all a man of the spirit, an idealist, a faithful Christian, a convinced Catholic. He enthusiastically participated in the renewal in the Church. And above all, he was a loving husband for my mother, and a devoted father for his sons. Good relationships were top priority for him. We could always approach him for advice and actual support. My father loved enjoying with my mother the many good things of life, the cozy gathering in the home circle, the holidays with the whole family in sometimes far corners of Europe.

My father was not a businessman. Money did not matter to him even though he often had to work hard for it. Human relations counted for him the most and he could get along well with everyone. He understood people with an enormous personal sympathy. His ultimate search was to find the full meaning of life, and he recognised the same search in others.

I have been analysing my father’s paintings and I am confident that analysis comes close to the truth, but remember that he never ‘explained’ his paintings to us. He left it to us to scrutinise them and discover the unspoken dimension for ourselves.

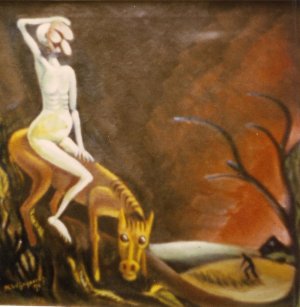

This applies, for instance, to his 1974 painting of the two women. I see it in the context of my parents’ attempt to counsel a couple of friends whose marriage broke up. Reason was the frustration of the wife. Her ultra-conservative husband had totally abandoned sexual intimacy with her. This caused a severe personal crisis for her, and she spoke openly about it. “When I was young, OK, I did not mind. But now I feel something is missing!” My father, who was also familiar with this phenomenon among both men and women from his knowledge of literature, painted the mid-life respectable ‘lady’ who becomes aware of the lustful young woman in her who still longs for recognition and fulfilment. Knowing my father I suspect that he also reflected on the unfulfilled desires living in himself, in all of us. It is interesting that he called this picture ‘freedom’. Accepting yourself as you are brings freedom.

This applies, for instance, to his 1974 painting of the two women. I see it in the context of my parents’ attempt to counsel a couple of friends whose marriage broke up. Reason was the frustration of the wife. Her ultra-conservative husband had totally abandoned sexual intimacy with her. This caused a severe personal crisis for her, and she spoke openly about it. “When I was young, OK, I did not mind. But now I feel something is missing!” My father, who was also familiar with this phenomenon among both men and women from his knowledge of literature, painted the mid-life respectable ‘lady’ who becomes aware of the lustful young woman in her who still longs for recognition and fulfilment. Knowing my father I suspect that he also reflected on the unfulfilled desires living in himself, in all of us. It is interesting that he called this picture ‘freedom’. Accepting yourself as you are brings freedom.

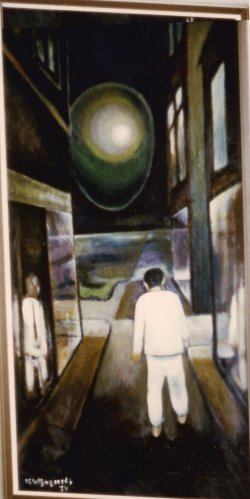

In the ‘Sleepwalker’ my father painted himself as walking in a dream. He made this self portrait in 1974, shortly after his heart attack and just a few years before he would die. Death looms on the horison. My father is asking himself who he really is. He sees reflections of himself in various window frames, but cannot make sense of them. He is still walking, but where will it lead him? In the distance though shines the moon. And the moon was a symbol of love for him. During the war my father and mother had agreed to go out at night and look at the moon, if ever they would be separated. I remember us doing so in the camps of Sukabumi and Ambarawa. The moon was the symbol of love, uniting us in spite of not even knowing where the other was. “Oremus et Amemus” (Let us pray and love) was the slogan my father had attached to the moon. Is it a coincidence that, in spite of his stumbling in the dark, he steps forward to meet the moon?

In the ‘Sleepwalker’ my father painted himself as walking in a dream. He made this self portrait in 1974, shortly after his heart attack and just a few years before he would die. Death looms on the horison. My father is asking himself who he really is. He sees reflections of himself in various window frames, but cannot make sense of them. He is still walking, but where will it lead him? In the distance though shines the moon. And the moon was a symbol of love for him. During the war my father and mother had agreed to go out at night and look at the moon, if ever they would be separated. I remember us doing so in the camps of Sukabumi and Ambarawa. The moon was the symbol of love, uniting us in spite of not even knowing where the other was. “Oremus et Amemus” (Let us pray and love) was the slogan my father had attached to the moon. Is it a coincidence that, in spite of his stumbling in the dark, he steps forward to meet the moon?

Love for my father, ultimately, resided in God. All the good things in the world pointed to God. God is our last and final destiny, the deepest fulfilment of meaning in our life. Goodness, love, beauty were intimately connected for my father. And their source? Listen to what he wrote in a book on art appreciation:

“All beauty on earth reflects the dimension of divine beauty. It is, as it were, a foretaste of it. It is as if God, while showing us beauty here on earth, wants to tell us: ‘Later on, you will enjoy this beauty and enjoy it in a more satisfactory way.’ The perfect beauty, the infinite beauty, is God himself. After all, the divine dimension possesses all qualities to the highest degree. So also beauty. That beauty is what we will enjoy in heaven. In heaven we will be immersed in God’s dimension, there we will enjoy infinitely glorious Beauty. It will affect us, stir us, move us as nothing else can.”

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage