The second Vatican Council has probably been the most important event for the Catholic Church in the twentieth century. By a stroke of good fortune for me, its preparations and opening happened during the time that I studied in Rome. It provided me with a unique insight into the inner tensions within the international Church community, notably between dyed-in-the-wool conservatives on the one hand and open-minded reformists on the other. It also created in me, for the first time, a feeling of deep anger at the abuse of authority by traditionalist Church leaders.

To understand the importance of the events of the time, it should be remembered that in the western part of the Church, Latin was still the official language of the liturgy and of theological study. This had world-wide effects for mission areas in Asia, Africa and South America for these had been evangelised by missionaries from the West. Missionaries had introduced Latin everywhere. For all practical purposes, Latin had become the Church’s official lingua franca through much of the globe.

This, of course, made no sense. In Indonesia, for instance, where I had been born, no one had the slightest connection to Latin. The ordinary people spoke Malay or various local Javanese dialects. I had been delighted, therefore, when at Nijmegen in 1959 an international study week on Mission and Liturgy recommended that the liturgy in each country should, as far as possible, adopt the language of the area. In fact, a year later bishops and priests began to introduce the vernacular in some liturgical contexts in the Netherlands. I myself eagerly adhered to this policy – with perhaps a little too much zeal . . .

During one of my summer breaks from Rome, an uncle of mine, Karel van Hoesel , who was parish priest of Buuren and Geldermalsen had asked me to take over his parish for a month so that he himself could go on a holiday. So for a month I was an acting parish priest. At the time priests in Holland had begun to read the liturgical readings from Scripture in Dutch, but the rule prescribed that one should first read the text in Latin before reading the Dutch translation. This actually was quite insipid. Most priests would quickly rattle off the Latin in a muffled mutter and then read the text once more in Dutch, this time audibly and understandably.

Following the example of some others, I boldly decided to omit the useless reading of the Latin before reading the Dutch. A more difficult decision arose when one of the older parishioners was on the point of dying. Again, the official regulations prescribed that the last rites should be performed in Latin. This made absolutely no sense since the dying person did not understand a word of Latin, neither her family. But I was worried of any consequences of conducting the whole ceremony in Dutch.

I quickly consulted a theologian in Nijmegen. “Will the anointing of the sick be valid in Dutch?”, I asked him. “Will it still be a sacrament?”

He reassured me.

“Yes, it will be valid sacrament. The language of the prayers does not belong to the essence of what you are doing.”

Fine. So I conducted the whole service in Dutch. This seemed all the more important to me because most of the members of the family in question were no regular churchgoers and mumbo-jumbo in an ancient language would only make matters worse for them. I anointed the woman using the Dutch translation of the sacramental formula.

When my uncle returned from his holiday, he heard from me what I had done. And – to my relief! – he wholeheartedly applauded. He told me I had been right. He himself would do the same from now on.

Now to come back to Rome and the preparations for the ecumenical Council. Various commissions had been set up, one of them dealing with liturgical reform. It so happened that I got to know one of the members of the liturgical committee, a certain Bishop Theo Valemberg, who was a retired missionary Bishop from Borneo. He was a short man, a Capuchin monk, then in his seventies, with a white beard and long white hair and sparkling blue eyes.

During a visit to our Mill Hill community in Rome, Theo told us that certain conservative members of the commission were systematically suppressing demands from missionary countries that the liturgy should be adapted to the vernacular. It was a first indication of what was to come.

“How can they get away with such a thing?!”, I asked with indignation.

“Easy enough”, he said. “The Roman Curia controls the commission. They occupy all leadership positions. Also the administration is totally in their hands. The secretaries and correspondents report to the Curia.”

It made me feel uneasy. Rightly so, as it turned out.

The big blow

On a particular weekday in 1962 all the students at Rome’s theological universities were invited to attend a special gathering in the Gesù, an ancient Church in the middle of Rome. I felt quite excited about this because we were going to be addressed by Pope John XXIII whom I had come to like. He had a very human touch. During his weekly Sunday address from the balcony of his rooms overlooking St Peter’s Square and during general audiences, I had seen how he could really speak to the hearts of ordinary people, just bubbling away in colloquial Italian whenever he could. So I was wondering with pleasant anticipation what this special meeting was going to be about.

Imagine my surprise when, at the beginning of the ceremony, before the Pope even began to speak, it was announced that the Pope would be signing an important decree. It turned out that this decree, which was read out to us, imposed Latin on the whole Church with a new, unknown ferocity. Latin was to continue throughout all liturgies. Latin was also to remain the central language for all theological studies. Candidates for the priesthood had to be tested specifically for their ability to learn and speak Latin. The decree literarily stated: “Any applicants for the priesthood who have no aptitude for learning or speaking Latin should not be admitted to ordination, whatever other good qualities they may possess.”

The decree was read to us by Cardinal Antonio Bacci, an expert in Latin, who had been the head of the obscure Vatican office entitled ‘Briefs to Princes’ for the last 30 years. It was the office entrusted with translating all official Church documents into Latin, since Latin was considered the official language of the Church. Now Bacci was an archconservative, a close associate of Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, the head of the Holy Office and the leader of opposition to reforms in the Church. At once it was clear to me that this decree, just a few months before the opening of the International Council, was a master stroke by traditionalists to close, as they thought, any doors to introducing the use of the vernacular.

I find it hard to describe how angry I was.

I refused to even listen to what the Pope said afterwards. I was just hopping mad at the thought that this scheming plan by a few Cardinals in the Roman Curia might block some of the necessary reforms that the Vatican Council was going to discuss.

Sitting among the ruins of in the Forum Romanum

After all, at the time I still considered the Pope as the person to look up to for real leadership. And now his authority was being abused in order to keep the Church firmly chained to its mediaeval dungeon!

After the gathering had been dissolved, I cycled round Rome in a state of fury. Because as usual I had come on my bicycle. I now travelled around to various ancient sites: the Coliseum, the busy streets of a market in Trastevere, the Piazza Argentina with its hundreds of wild cats climbing over ancient ruins of buildings that had been left exposed in the middle of the square, the old forum Romanum and many other places that I could think of. I ended up in the park on top of the Gianicolo hill with its magnificent views over the city of Rome.

Here had stood the temple of Janus, the god whose head possessed two faces: one turned eastwards, the other westwards. Here the ancient augurs of Rome had studied the entrails of cattle or the flight of birds to forecast the future for anxious worshipers. I descended from my bike and sat down on a patch of grass. I looked down on Vatican City, the dome of St Peter’s Basilica towering in its middle.

The long history of Rome oppressed me. I called to mind the abuses of the papacy in century after century from the Middle Ages on. I felt the Church needed to free itself from this unnecessary burden, not so much the burden of central leadership which an international community needs, but of a central bureaucracy which was stifling the growth and development of authentic Catholic communities all over the world.

Again dark and ominous anger welled up in me. The image of Moses came to my mind. He climbed down from Mount Sinai cradling the precious tablets of the covenant in arms and then saw how down in the valley the people of God were dancing round golden calves! In a fit of sacred fury he had smashed the tablets to smithereens on a rock, before rushing down to unleash his wrath on Aaron.

What was I going to do?

I could hardly claim to be a Moses. The vision I carried of a dynamic, open Church were not tablets of the covenant written on by God’s own finger. But I refused to dismiss my dream of a vibrant Church as insignificant. In my own way I too was responsible for the health of the Church, like Moses had been for the relationship of his people to God.

It is hard, especially after such a long time, to re-live the storms raging in my mind and the prayers welling up from my heart. It all resulted in a firm resolution on my part not to let the traditionalist forces get away with their underhand tactics. Somehow or other the anti–reform movement had to be frustrated in its aims. I had no idea how that could be achieved, considering the power wielded by such a small group of determined Cardinals. But, acknowledging myself to be a fighter, I made up my mind that I would contribute in my own small way to make the dream of a relevant, vigorous and open Church come true.

The fireworks begin

In late September 1962 the 2200 Catholic bishops who were to take part in the Council converged on Rome. They were billeted in seminaries, colleges, tourist hotels, monasteries and convents. Our own Mill Hill house provided accommodation to ten of our own bishops who worked in eight different countries. Sparks of excitement hung in the air.

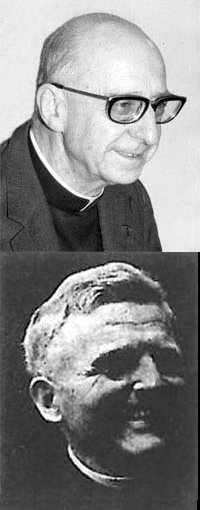

Fathers Lyonnet (top) and Zerwick, two of my professors at the Biblicum.

Talking to one of our bishops from North Borneo, I found out that the traditionalists had been at work in other ways. When the Bishop heard that I was studying at the Pontifical Biblical Institute, he enquired about two of our professors: Stalislas Lyonnet and Maximilian Zerwick. I told him that they were two brilliant New Testament lecturers, Lyonnet an expert on St Paul’s letters, Zerwick an authority on Biblical Greek and on St Luke’s Gospel. The bishop then told me in confidence that just before travelling to Rome, he and other bishops had received a letter to tell them that these two professors of the Biblical Institute had been suspended by the Holy Office on suspicion of teaching suspect methods of interpreting Scripture and that the whole Biblical Institute could not be trusted.

“The letter told us to keep this information secret”, he said.

Sure enough. I soon found out that the Holy Office had suspended the two Jesuits from all teaching. I realised that this was another ploy by Cardinal Ottaviani in order to intimidate the bishops before the discussion on Sacred Scripture which would take place during the Council. By sending their warning to all bishops of the world in advance, they were trying to discredit the real scriptural experts even before these could be consulted by the bishops.

Meanwhile it became clear that the more progressive leaders in the church had not be been sitting still either. Before the Council started, some of the key cardinals in Europe with their close advisers had met in Bonn. There they had been fully informed about the machinations of the Curia. So when the bishops started arriving in Rome, the European leaders began to divulge the information they possessed. It is not widely realised how big an influence, for instance, Dutch bishops played at this time. Although only five residential bishops had dioceses in the Netherlands, there were another seventy Dutch bishops working in over 50 missionary countries.

So I found myself suddenly being asked to drive our own six Dutch Mill Hill bishops in a minibus to a gathering in Nemi just outside Rome. There Cardinal Alfrink had invited all seventy-five Dutch bishops to a complete briefing on the situation in the Vatican. Of course, I myself was not present at that meeting, but I received a lot of information from one or two of the bishops who were friendly to me.

When we had returned home late that night, I discovered that the Dutch bishops carried copious documentation with them to meetings of the bishops’ conferences belonging to countries in Asia, Africa and South America in which they had dioceses. In that way in a short time most of the bishops coming to the Council were given advance information on the objectionable tactics employed by the Vatican offices.

At the same time a series of articles on the Curia was published in the New Yorker by someone with the pseudonym Xavier Rynne. It was obvious that the articles had been written with the help of insider information. These articles too documented the many ways in which conservative Vatican officials had been trying to manipulate the process of preparation for the Council.

The first big conflict within the Council itself came to a head during its opening business session. Cardinal Ottaviani presented to the members of the Council ready-made lists of participants for the ten major conciliar commissions that would have control over the key areas of discussion. Ottaviani and his allies had stacked the proposed commissions with bishops whom they knew to be conservative. Ottaviani brazenly told the general assembly of the Council that it would be nonsense to expect bishops from far-flung countries to assess the expertise of bishops residing elsewhere. Candidates for the commissions had to be selected centrally, he asserted.

However, now the European counter plan swung into action. Cardinal Liénard of France rejected Ottaviani’s proposal and suggested instead that the Council should adjourn for two weeks to give the bishops a chance to suggest other names for the ten commissions. Cardinal Frings of Germany seconded his proposal. The assembly embraced the European proposal.

Frantic negotiations now began between the many bishops’ conferences. The conference of each country was asked to prepare a list of the candidates from their own area whom they wanted to see appointed to particular commissions. These lists were then traded between countries, one country agreeing to adopt another country’s experts, in exchange for that country accepting their own. A true democratic process with everyone having a say . . .

And so the miracle happened. In spite of the huge number of bishops involved, new candidate lists for the various commissions were drawn up that carried the support of the majority of the 2200 assembly members. So two weeks later, when the Council met again, these new lists were adopted rather than the stitched-up lists that had been cunningly engineered by the Curia.

I heaved a sigh of relief when I heard about this happy development. But my joy was short lived. The first draft of a Council document submitted to the general assembly concerned sacred Scripture. It was entitled: “De Fontibus Revelationis” which means “On the Sources of Revelation”. Again, the Council members were told that this document was for personal use only. Fortunately most Council members had enough sense to realise that they needed expert advice to assess the value of the document. One of our Mill Hill bishops, Cees de Wit, the Bishop of Antique in the Philippines, who also happened to be the youngest bishop at the second Vatican Council, was one of my friends. He showed me the document in Latin at the end of that day.

When I read the text, my heart sank. It obviously was a frontal attack on modern scripture studies. As I perused paragraph after paragraph, I discovered at least eleven major errors. Though it was already late in the evening I decided it was important enough to clearly label these eleven errors with a good translation of the text and an explanation of what was wrong in it.

To give just one example, the draft document stated something like this:

“This sacred Council solemnly declares it to be a matter of faith that the Catholic Church has always held, taught and believed that every single word spoken by Jesus as recorded in the Gospels was literally spoken by him in that form.”

It is obvious that this is cannot be true. For instance, the eucharistic words spoken by Jesus at the Last Supper are recorded in different forms by Mark, Mathew, Luke and Paul. Mathew 26,28 reads: “This is my blood of the covenant”, whereas Luke 22,20 reports that Jesus said: “This cup is the new covenant in my blood”. Both phrases express the same reality of course, but their formulation is different. Though the evangelists faithfully recorded the substance of what Jesus said, they often interpreted his words according to their own theological themes and according to the needs of the audiences to which they addressed their Gospels. It is legitimate to ask, for example, did Jesus himself speak of a new covenant? Or was the word ‘new’ added in Luke 22,20 and 1 Corinthians 11,25 as a theological pointer to the ‘new covenant’ announced in Jeremiah 31,13-34?

Whereas the ‘Our Father’ in Mathew 6,9-15 follows a Hebrew formulation because Mathew wrote for Jewish converts, the ‘Our Father’ in Luke 11,2-4 has been adapted to a way of speaking familiar to Hellenistic audiences. Mathew still has: “Forgive us our debts,” (which may well have been the actual words spoken by Jesus), Luke translates the phrase as: “Forgive us our sins” which would be understandable to his Greek readership.

The enormity of the definition in the draft prepared by the Vatican is apparent. The Council was asked to define it as a truth of faith that every single word of Jesus as found in each gospel was the actual word spoken by him. It was obviously a mistaken proposition. But the implications lay deeper. For the pronouncement would have denied the whole process of gradual interpretation and elaboration of Jesus’ message by his followers during the first generation of believers.

As I reflected on the state of the draft, I felt despondent. I was painfully aware of the fact that of the 2200 bishops taking part in the Council very few had enjoyed the academic training needed to be aware of the true issues involved in the document. I thought of our own Mill Hill bishops: rugged bishops Jan Vos and Jaap Buis working in Malaysia’s Kuching and Kota Kinabalu; the shrewd organizer Jaap de Reeper pioneering the Ngong diocese among the Masai in Kenya; energetic Niek Hettinga bishop of Rawlpindi in Pakistan; aging Wim Bouter of Nellore in India and neophyte bishop Cees de Wit of the Philippines. Would they be a match against the wily, persuasive and overpowering pressure of the Vatican moghuls?

I suddenly saw, as in a nightmare, that it would be so easy for even a large body of ill–informed men to be steamrolled by the heavy–handed leadership of a small group of determined Cardinals. I must admit that I began to almost despair, wondering if the Church would be able to escape this disaster.

After spending the whole night at finalizing my critical assessment of the draft and writing everything down, I handed it next day to Cees de Wit with the request for him to make copies of it and hand it out to as many bishops as possible – which he promised to do.

At the Biblical Institute later that day the American Professor Moran told me that the draft on Revelation had been crafted by Cardinal Ottaviani himself with the help of Cardinal Rufini of Sicily and conservatives such as Professor Salvatore Spadafora of the Lateran University. Before the preparatory commission concluded its proceedings, they had invited two representatives from the Biblicum to attend. This included its Rector Professor Vogt. This was done so that it could later be claimed that experts from the Biblical Institute had been involved in the production of the draft . . . But, when, on seeing the draft, the two experts from the Biblical Institute had voiced their strong objections, their intervention was rejected as coming too late in the process . . . Of course, Professor Vogt on his part had seen to it that the European Bishops’ consortium was informed of what had taken place. Vogt was a German and had the ear of Cardinal Frings.

I also learnt from Professor Moran that the suspension of Zerwick and Lyonnet had a happy side effect. They were being invited by many gatherings of bishops who wanted professional guidance and their suspension had freed them from lecture duties. So they could accept invitations round the clock. The Frenchman Lyonnet addressed French-speaking bishops of France, Belgium, Switzerland, Gabon, the Ivory Coast, the Cameroons, the Congo and Zaire. Zerwick explained the situation of scripture studies to the German-speaking bishops of Germany itself, Austria and Switzerland.

Determined as I was to put my oar in, I prepared an article defending Zerwick and Lyonnet for the Gregorian University students’ magazine Vita Nostra. The suspension of these two professors was totally unjustified, I wrote, because they were both deeply committed Christians and highly competent scholars. As a member of the editorial committee I expected it would be relatively easy to get the article placed. Instead, I was summoned to Father Joseph Fuchs, a well-known German moral theologian who was the spiritual guide of Vita Nostra.

“I agree with every word you say in your article”, he told me. “But, please, withdraw it.”

“Why?”, I asked.

“It’s wiser to avoid confrontation.”

“Should we not speak up when the Holy Office is wrong?”

“Look here”, he said. “I understand your indignation. You are right. The Holy Office is wrong. But here at the university we are in a vulnerable position. We know that Cardinal Ottaviani has spies in all our lecture halls. Everything we say is monitored and reported on. Various of our professors have been called in for questioning in recent years . . . All our Jesuit institutions in Rome are under such scrutiny. Please, don’t tell others about it.”

“But that is ridiculous!”, I protested. “They are bullying you. Should you just take that lying down?”

“Open conflict will harm us”, he replied. “For your own sake and that of the Gregorian, please, withdraw your article. I am requesting you to do this as a favour.”

I withdrew the article. I did not want to upset a good man like Joseph Fuchs but to this day I am not sure he was not too timid. Abuse of authority can only be cured when it is exposed.

The discussion on the scripture document started in the Council hall on the 14th of November 1962 and lasted for six days. There was significant opposition to it, both because of its dismissal of modern scholarship and its separation of scripture and tradition. When the German Cardinal Bea, head of the Secretariat for Ecumenism, and Cardinal de Smedt of Belgium demanded that the whole draft be rewritten, Cardinal Ottaviani retorted that the draft could not be rejected because it had been approved by the Pope. This was not true, of course. The Pope had approved its being the basis for discussion. He had not approved its contents. Moreover, article 33.1 of the Council’s rules clearly stated that drafts could be discussed, amended or rejected . . .

It came to a vote on the 19th of November. The question put before the bishops was: Should the draft be rejected? Now, in Council jargon, Placet (I am pleased) means ‘yes’, Non Placet (I am not pleased) means ‘no’. Officials greatly confused the issue by saying: “If you like the draft, vote ‘I don’t like it’ (in Latin: Si placet, scribe ‘non placet’); if you don’t like the draft, vote ‘I like it’ (In Latin: Si non placet, scribe ‘placet’).” This caused much hilarity. Eventually, when the votes were counted, it became clear that the draft was rejected, but by a small margin only. This caused a stalemate. Outright rejection required a two-thirds majority. Next day the Pope intervened. The draft was rejected, and another commission appointed to produce a new draft . . .

Again a moment of immense relief for me, as well as the realization that I had underestimated the intelligence of the bishops no less than the power of the Holy Spirit. The Council had shown it was capable of steering the Church to reform.

The document on the Liturgy sailed through stormy waters and was the first Council Document to be formally ratified a year later. Full participation by the faithful was stated to be the main aim of liturgical reform. Translations of liturgical texts into vernacular languages was permitted. Another victory, the significance of which I what see with my own eyes in India.

John Wijngaards, My Story – My Thoughts, Clash of minds

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage