Another project I was involved in was the translation of the New Testament into Telugu. The older Catholic translation was totally out of date and in direct conflict with the Protestant version – which caused endless confusion.

For example, the French missionaries who had evangelised Andhra Pradesh in the 18th century, had rendered Greek biblical names into corresponding Telugu designations. ‘Peter’ became ‘Râyappa’ [rock-man], ‘Paul’ became ‘Chinnappa’ [small-statured man], ‘Jesus’ was ‘Djêsuvu’. The Protestant bible translated these names as ‘Pêturu’, ‘Pauludu’, ‘Yêsu’. The Catholic rendering of more than 100 names in the Gospel of Mark for instance, was different from the Protestant one in every single case. Hindus scoffed at Christians being so divided that they could not even agree on a common Telugu name for Jesus!

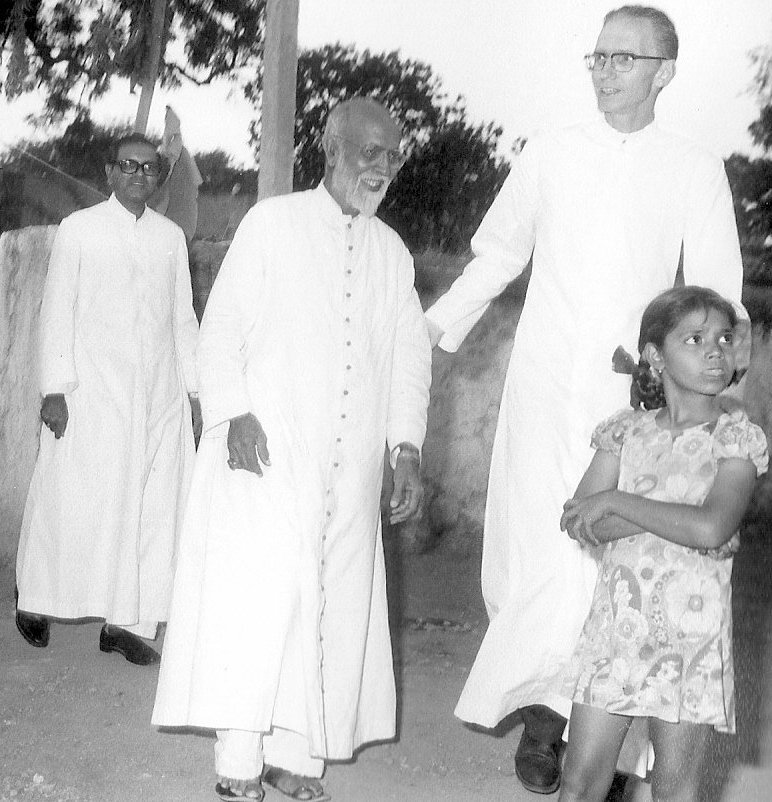

Archbishop Arulappa, Bishop Mummadi and I.

So we began a process of preparing a new ecumenical version of the bible in Telugu. A cross-denominational committee was set up. On the Catholic side it included Bishop Ignatius Mummadi, Bishop of Guntur who had previously been editor of the Catholic weekly Bharatamithram; Dr Gali Bali, my scripture colleague in St. John’s College; Fr P. Jojayya SJ who held a master’s degree in Telugu literature and me.

We met on various occasions in different towns of Andhra Pradesh. Our Protestant colleagues found in their ranks a bible lecturer from the Church of South India, a Baptist pastor and ministers from a variety of denominations. They were well-intentioned men, but, as experience showed, utterly ill-equipped for the job.

I recall one day when we were trying to translate Jesus’ parable of the sower: “A man went out to sow seed on his field . . .” (Mark 4,3-8). We spent a whole morning bickering about the meaning of the first line. Precise fidelity to the exact literal sense of the original was the greatest priority for most of our Protestant friends. These are the typical remarks that each led to fruitless discussions:

- “The text says a man went out, not a woman. Saying a ‘male man’ would be more accurate.”

- “It’s clear that only one man went out, not two or three. This should be expressed.”

- “The original Greek does not mention a man at all, nor the seed. The Greek text reads: ‘A sower went out sowing’. That is all. But we have no word for ‘sower’ in Telugu. May we use ‘farmer’ instead?”

A number of the committee members turned out to be weekly preachers in their churches who would dig theological meaning from each word in a sentence. The end result in Telugu was the monster phrase: ‘A single farmer went out sowing . . .”

At the same time we had started negotiations with the Protestant Bible Society about an eventual joint publication of the Telugu Bible. Bishop Ignatius Mummadi and I travelled to Bangalore and held prolonged meetings with Rev Arangaden, Secretary of the Indian Bible Society, and other officials. These revealed a large revenue of resentment against Catholics in other Christian denominations. We realised that we had to find another way. It suddenly showed itself – through the good services of another Protestant ministry.

Bible Translation Seminars

The American Bible Society came to the rescue. They organised training sessions for translators during the dry season in Ooty, a hill station in the Nilgiris mountain range of Tamilnadu. And these training sessions were run by real experts: Eugene Nida and Robert Bratcher, the well-known translator of the Today’s English Version of the New Testament.

I took part in two of them. In the first one as a keen learner, two years afterwards as one of the lecturers – by invitation.

The American approach was revolutionary. It had been developed by Eugene Nida and was called translation by ‘dynamic equivalence’.[i] It carefully distinguishes the deep structure of meaning from the surface structure through which the meaning is expressed in a particular language. Paul’s blessing in Ephesians 1,3-10, for example, is a typical Greek string-phrase consisting of 129 words. A literal translation into English is unreadable. The dynamic equivalent found in ‘Today’s English Version’ renders the meaning accurately in seven sentences.

On my return to Andhra, I reported my findings to my Catholic colleagues on the translation team. We realised that we needed to adopt a drastically new approach. I also began to analyse in more detail the elements that make up the surface structure of the Telugu language. This affected: linguistic organisation of sentences, terms and concepts, metaphors, literary styles, interpretation of experience, proverbs, prayers, stories and songs. The first five belong to language as the daily medium of expression. The final group of four contains ready-made literary units that have been totally assimilated. I set myself the task of collecting precise data regarding these components in the Telugu language area.[ii]

I found, for instance, that the existing Bible translations in Telugu sounded like ‘foreign-language speak’. A test on both the Roman Catholic and the Bible Society New Testament translations established the following serious shortcomings:

- an average sentence length (13 words) almost twice that of ordinary Telugu (7 words);

- an unusual proportion of verbs, nouns and pronouns;

- far too high a percentage of passive verbs, of conjunctives, and of introductory quotation formulas;

- serious deviations from the normal pattern of sentence construction.

Small wonder that the Bible had acquired a reputation of having been written in very poor Telugu. Half-intelligible westernized language was commonly referred to as Bible Telugu among educated Hindus. “I wanted to read the Bible, but looking at one page was enough for me”, characterized the honest reaction of many Hindu enquirers.

The mismatch

Then there was the question of terms and concepts. When the Christian message is translated into a language culture, much depends on the adoption of accurate and felicitous terms. The problem is an old one. The Christian community in early Rome struggled with it; in some cases it adopted Latin terms and gave them a new meaning (sacramentum; ministerium); in many other cases it stressed the uniqueness of Christian concepts by introducing Greek terms (eucharistia; baptisma; presbyter).

There was general recognition of the fact that Christian terminology in Telugu badly needs to be revised. Investigation of the terminology used in the three most widely used texts of instruction: a Bible history for the primary school, the handbook for catechists, and a textbook for high school students showed that the situation was highly unsatisfactory. Many terms were triple or quadruple compound words of Sanskrit origin and therefore difficult for ordinary people to learn or remember. ‘Grace’ was rendered as dêvavaraprasâdamu, original justice as parishudhdhamunubhâgyamainasthiti. Many terms suggested a mistaken meaning. For instance, the word for ‘sacrament’, dêvadravyânumânamu, could be read, in ordinary Telugu, as meaning: ‘suspicion’ (anumânamu) of ‘God’s treasure’ (dêvadravyamu).

Another source of embarrassment was the apparent disregard of the normal semantic connotations of Telugu religious terms. For human ‘love’ of God, Christians used a term normally employed for love between husband and wife, or a mother and her children. Môkshamu means a state of bliss, but Christian texts spoke of it as a place – ‘heaven’ – where one was going to meet people and which one needed to enter by a gate.

The metaphors in scriptural texts proved far removed from those common in Telugu. Animals, for example, conveyed distinct characters in Telugu literature, notably in the stories of the Pancha Tantra. The wit and wisdom of daily life had added its own verdict on animals and the lessons we can draw from them. Comparison with the function of animal metaphors in the Gospels and ordinary Telugu thought, bore out a horrendous mismatch.

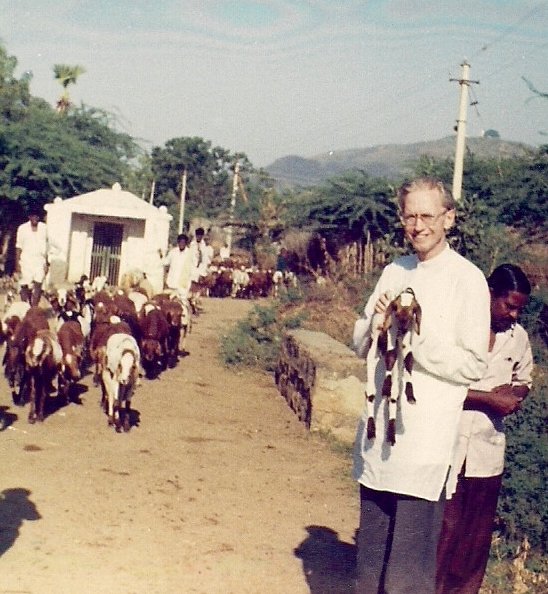

Me, holding a typical sheep from the Andhra countryside.

Part of it was due to context and culture. Many animals that occupy an important place in Telugu metaphorical thinking do not occur at all in the gospel message: the bull, the elephant, the cow, the monkey, the cat, the tiger, the crow, the buffalo and so on. More seriously, images of scriptural animals conveyed a distorted meaning. In Telugu thinking the sheep is not an animal to be pitied, loved and cared for, but the symbol of unthinking, stupid, herd behaviour. Unfortunately, the situation could not be remedied by substituting known animals for unknown ones in particular Bible texts. Footnotes to the text were essential.

Local experience and language

It has been said that culture may be compared to a floating iceberg of which only the top can be seen and of which ninety per cent remains under water. One all-pervading element which normally remains invisible, but which determines the meaning of words and events, is the commonly accepted interpretation of experience. This interpretation is made up of: norms by which persons and things are judged, expectations and aims, and the values attributed to situations or events. Experiential interpretation is difficult to define, as it belongs to the implicit and subconscious realms of thinking. One can only understand this cultural interpretation of experience by making the culture in question one’s own, by internalizing that culture.

Examined from this point of view, scriptural texts presented great problems of interpretation in India. The parable of the marriage feast (Matthew 22,1-14) may serve as an example:

“The kingdom of heaven is like a king who gave a feast for his son’s wedding. He sent his servants to call those who were invited, but they would not come. Next he sent some more servants. ‘Tell those who have been invited’, he said, that I have my banquet all prepared, my oxen and fattened cattle have been slaughtered, everything is ready. Come to the wedding.’ But they were not interested . . . etc.”

To Telugu listeners, the parable gives rise to at least eleven well-founded questions:

- Who are those who received the first invitation? Why is it not said that they are the king’s relatives and friends who are normally invited to marriages?

- How could the king commit the impoliteness of sending a verbal invitation through his servants?

- Why are the guests invited to the meal and not to the marriage ceremony? The Telugu invitation formula says, ‘Please come to impose hands on the bride and bridegroom and share with us sandalwood, flowers and betelnut’.

- Why are the bride and bridegroom not mentioned at all in the parable?

- Why this crude mention of the bulls and cows that have been slaughtered? The cow is a sacred animal and the bull such a dear friend that it is buried after death and never eaten.

- Why should the readiness of the meal be adduced as a reason for hurry? Instead, in India it would be understandable if the king were to be worried about the passing of the astrologically correct time for the marriage rite.

- How can the king take revenge in such a barbaric and naive way, namely by killing those who refused to accept his invitation?

- How can we imagine guests ‘lying at table’? Why don’t they sit in rows on the floor as is the Indian custom?

- How could the king be so ungracious as to become angry with one of the guests? And, for that matter, what is a ‘wedding garment’?

- Why does the king not content himself with a simple removal of the impolite guest from the festive hall? Why this peculiar treatment of ‘binding his hands and feet’ and ‘throwing him into outer darkness’?

From examples such as this one, which could be multiplied indefinitely, it was clear that much more than word for word translation was required. To do full justice to the Bible message, it needed a dynamically equivalent re-telling within the local cultural context and the adoption of India’s own literary forms.

The Telugu language has its own literary styles. The Pancha Tantra, and other instructive books of the same genre, employ a form of story that is known as neethi kadha, i.e., ‘story with a moral’. These stories contain four elements: a sâmitha or proverb that summarizes the lesson, the upamânam or story, the şlôkam or poetic expression of the lesson and the neethi, i.e. the application. Father Sanivarapu Sleeva Reddy, who researched these matters with me while he was a student in college, later published fourteen parables of Christ in the form of neethi kadhalu with considerable success.[iii]

Telugu Bible translation

It may seem that I have deviated from the original thrust of this chapter: my involvement in the translation of sacred scripture into Telugu. However, my diversion served a purpose. It shows that I myself and Catholic members of our translation committee began to realise that only a radically new approach would do justice to the job.

When we met again, now as a Catholic translation committee, we took some important decisions. We resolved to produce our own translation independently from the Protestant Bible Society, while maintaining friendly relationships. Also, for ecumenical reasons, we agreed to adopt the Telugu translation of biblical names favoured in Protestant circles.

Moreover, we decided to adopt the principle of ‘dynamic equivalence’ advocated by Eugene Nida. Cultural anomalies in the text would need to be explained in footnotes, but the text itself should be phrased in first-rate Telugu. It should not only be easily understandable to the ordinary Telugu reader but at the same time be a delight to those well versed in literature. Up to then all vernacular translations had been unnatural, stiff, too literal and obviously of foreign origin. We were determined to break with that tradition.

It should not be thought that this ‘literary’ excellence was no more than a whim to please scholars and critics. We strove after the literary quality of the new translation on theological grounds. In 1971 the translation committee expressed its purpose as follows – (I translate from the Telugu):

“We try, as well as we can, to follow the forms of expression in the original language. But whenever necessary we will not be afraid to render the meaning in characteristic Telugu idiom. Rather than sacrificing the meaning to external words we make it our main task to render the teaching of Christ as powerfully as possible (2 Corinthians 3,4). The character of the Telugu people lies in its language [as a Telugu saying asserts]. Our people have drunk this language with their mother’s milk. This language means everything to them. It is in and through the genius of that language that we offer them the good news of Christ.[iv]

To achieve this purpose, we followed the new translation procedure of the American Bible Society.[v] A well-known literary writer was chosen as the first draft writer: Mr. Kondaveeti Kavi, who had earned two special Telugu literary titles: kavirâzu (king of poets) and kalaprapurna (completion in art). Being a spontaneous thinker in the Telugu language, a Hindu and college lecturer, Kondaveeti would not make the mistake of falling back into second-grade Telugu, or worse still, into Bible-Telugu. Therefore, not only the formulation of the first draft, but also, after exegetical corrections pointed out by the translation committee, the final amendment of the text was left to him.

On the 22nd of March, 1973 the Bishops’ Conference of Andhra Pradesh released a new translation of the Four Gospels in Telugu under the title Rakshana Vêdam, the ‘holy treatise on salvation’.[vi] The text was soon acclaimed by Telugu scholars as a genuine Telugu piece of writing. This release was an important event. It was important not only because Telugu is the second biggest language of India. Neither merely because of the fact that it was a subsidized edition costing people no more than one Rupee per copy. It was an important event because the translation marked the beginning of a new approach in theology and evangelization, and I am proud of having been part of that.

[i] E. Nida and Ch. R. TABER, The Theory and Practice of Translation, Brill, Leiden 1969.

[ii] J. Wijngaards, ‘The Bible in an Indian Setting’, in The Bible is for All, ed. J. Rhymer, Collins, Glasgow 1973, pp. 154-175.

[iii] Sanivarapu Sleeva Reddy, Neethikadhâvali, Secunderabad 1970.

[iv] Preface to St. Matthew’s Gospel in Telugu, Shri Lami Press, Guntur 1971.

[v] E. A. NIDA and Ch. R. TABER, The Theory and Practice of Translation, Brill, Leiden 1969, pp. 174-188.

[vi] Rakshana Vêdam, Shri Lami Press, Guntur 1976.

John Wijngaards, My Story – My Thoughts, Part Three. MISSION IN INDIA

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage