In the previous chapter I have already referred to the fact that my place of residence in India was Hyderabad in the State of Andhra Pradesh. In this chapter I will introduce that part of the world at the hand of some adventures I experienced during my stay there. India presented plenty of challenges.

Map of the seven dioceses of Andhra Pradesh in 1975.

Let us start with Patibanda in Guntur District, a flourishing village surrounded by rich agricultural land. The larger houses in the village belong to members of the higher castes: Brahmins who minister in the local Hindu shrine, Kommatis who ran haberdashery shops and Reddys, the landowners who dominate social life. The subservient castes of which there are 106 in Andhra Pradesh, live in smaller dwellings: the washermen, toddytappers, weavers, potters and so on. Finally on the outskirts of the village outcastes, such as Mâlas and Madigas, occupy clusters of small clay huts.

The Telugus are actually a mixture of the ancient Dravidian population that inhabited the South of India and the Indo-Germanic Aryans who invaded from the north. This blend can still be seen in their language, culture, architecture and art.

I came to Patibanda to attend a meeting of Young Christian Farmers, a movement I was trying to introduce to our dioceses. I had brought with me a top official from the YCF headquarters in Paris and two French girls with experience of the movement. I had invited them to come over for this event. The YCF movement, I should explain, which sprang from the Young Christian Workers founded by Joseph Cardijn of Brussels, teaches young farmers to engage in responsible action to change their own society. It is based on the method of See, Judge and Act. Having watched its success in England, I realized its potential for Andhra Pradesh where the laity had generally been reduced to assuming only passive roles.

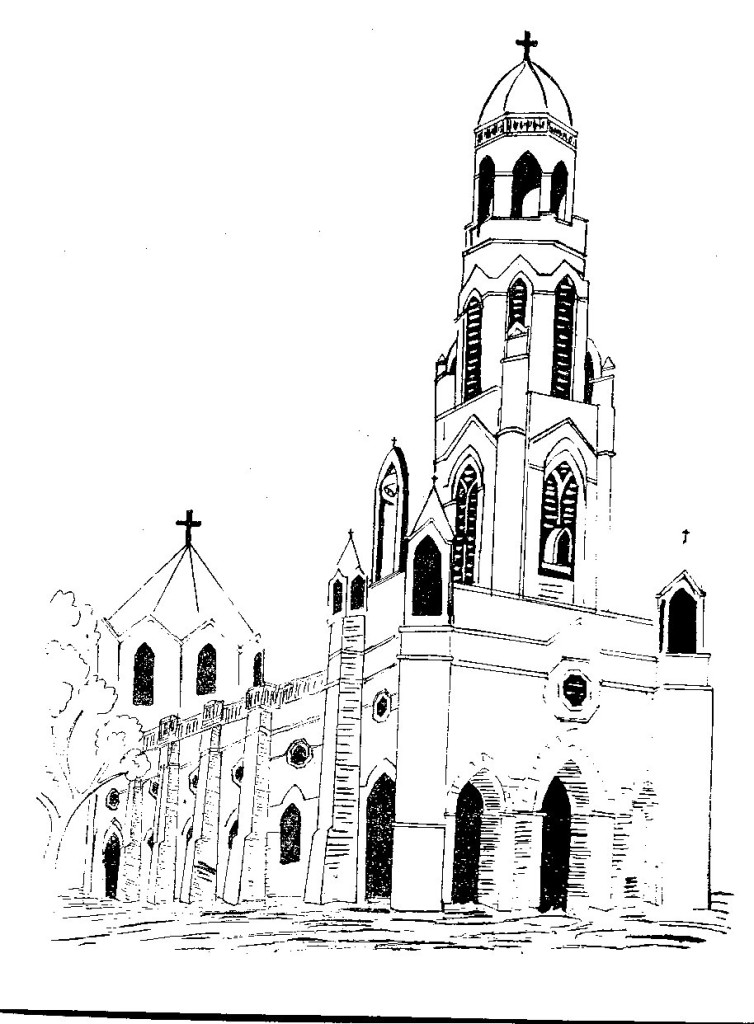

Patibanda Church, built through the contributions of the Catholic farmers of the village.

Now Patibanda was an excellent center for innovation. Its Catholic community, overwhelmingly Reddy, traced their conversion to Jesuit missionaries as long ago as 1597. The Catholics of Patibanda, prosperous farmers as they were, had numerous offspring. In the course of the centuries groups of young Catholics would buy up land in other parts of Andhra Pradesh and establish new communities there. In total thirty new Catholic villages were founded by Patibanda. Patibanda itself also produced many vocations: 18 priests and 150 religious sisters in half a century. The village of Mattampalli in Nalgonda District, one of Patibanda’s foundations, produced 10 priests and 24 sisters.

Enough for the background.

We opened our meeting in a hall of the local school. Priests were present, as well as sisters and prominent lay people. Fr Alam Chinnappareddy, who had been my student at the seminary, presided. I introduced the Young Christian Workers, explaining their aim and methodology. “The young farmers will meet regularly”, I said, “discuss the situation in the village and consider what action to take if anything is wrong.”

Almost immediately I was challenged by an old parish priests with an impressive white beard.

“You’re bringing over a movement from Europe”, he said. “What use is that in India?”

“Our laity have to learn how to actively involved in improving their community”, I replied. “The method can be applied anywhere, whether in Europe or in Andhra. It moves through the three steps of See, Judge and Act. Small groups learn how to recognize what’s happening in their own village, how to discern what’s right or wrong in the circumstances and how to adopt decisions about what should be done.”

“OK”, he said. “But the guests you brought over from France – I presume they grow wheat and grapes. Our farming is different. We grow rice, chilies, tobacco and cotton. Our culture too is different.”

“You are right”, I said. “Adaptation is essential. Remember though that the See, Judge, Act method can be used here too. Human beings are the same everywhere.”

At the end of the day it was decided to give the YCF a try in the diocese. Two Catholic farming girls from the movement in France stayed behind. They were made welcome in a rural village where they helped to form a first vibrant group of active teenagers.

Joachim, the official from headquarters in Paris, travelled back to Hyderabad in my jeep. On the way we had an interesting encounter. We picked up the controversial politician Chennareddy who stood on the side of the road because his Ambassador car had broken down . . . This gives me the chance to introduce another face of the region.

Telangana

In the 16th century, Persian forces had invaded the north of India. They established the Mogul Empire that took control of large slices of the country. Mogul generals also conquered part of Andhra Pradesh founding their own small dynasties. In the 18th century, Andhra Pradesh fell apart into three Muslim and five Hindu kingdoms.

Mir Osman Ali Khan, nizam of Hyderabad.

Smack in the middle lay Hyderabad governed by a Nizam who ruled the seven provinces of Telangana. When India became independent, the Nizam refused to join. The Indians responded by simply annexing his territory. In 1956 Telangana was integrated into the Indian state Andhra Pradesh. The last ruling Nizam, Mir Osman Ali Khan, was stripped of all his powers. But as a sob he was allowed to retain the title ‘Nizam’ to his death.

When I arrived in Hyderabad in 1964 the Nizam still made his presence felt in the city. He owned 7 wives and 43 concubines. Whenever the Nizam drove around Hyderabad in his open Rolls Royce, parents would quickly hide their teenage daughters for the Nizam had been known to point at attractive girls and summon them to his palace . . . Most of the Nizam’s 149 children studied in our Catholic schools and colleges.

At Christmas, the Nizam with wives, concubines and children would occupy the central nave of St Joseph’s Cathedral during midnight mass. As a devout Muslim he thus wished to express respect for the ‘prophet’ Jesus on his birthday. Catholic parishioners objected. In the end, my friend Archbishop Mark Gopu, usually timid man, took the most courageous decision of his life: he told the Nizam in as diplomatic a manner as he could muster, that only baptized people were allowed to take part in the Eucharist. It was courageous because normally nobody ever contradicted the Nizam. For instance, whenever the Nizam had agreed to come to a function at a fixed time but then arrived late, all clocks in the venue were hastily re-set to show the time he had agreed to come. You simply could not show the Nizam that he had come late!

Up to the time of his rebuff the Nizam had generously provided funds for the Cathedral to run a daily soup kitchen for the down-and-outs. Everyone assumed it would now stop. But to the Nizam’s credit he continued to fund the soup kitchen. He did not want the poor to suffer and this was typical of the man. Though one of the richest princes in the world, with a 185-carat diamond paperweight on his desk, he preferred to wrap himself in a simple wooden blanket when he felt cold, just as the ordinary man on the street would do.

I have digressed. Within Andhra Pradesh State, the original princedom of the Nizam, Telangana, remained a separate entity with its own history and culture. Soon serious conflicts arose between Telangana leaders and new Telugu politicians from Rayalaseema and coastal Amdhra. It led to the so-called Telangana riots of 1969 and later. More than once, when crossing the city on motorbike, I found myself surrounded by demonstrating Telangana students who wanted me to take sides. Well, Mr Chennareddy whom I picked up from his stranded vehicle was the chief architect of the Telangana unrest.

While driving back to Hyderabad I introduced Chennareddy to my French guest. He was visibly displeased. “Foreigners should not meddle in Indian affairs”, he said. He backtracked a little when I explained that Joachim Lebot was an expert on interactive cooperation who was simply teaching this skill to farmers. I dropped Chennareddy at his house. Not long after that I read in the papers that Indira Gandhi, then Prime Minister of India, had offered Chennareddy the post of Governor of Bihar State. That put a temporary stop to the Telangana movement . . . .

Catholics in the town parishes of Hyderabad reflected the mixed population of the city. Among them were found Telugus, middle-class Goans and Mangalorians, Malayâli businessmen from Kerala, Tamils who typically had come to Hyderabad as servants of the British and some Anglo-Indians. Most of them belonged to the disadvantaged classes.

In 1976 for example, of the 160 Catholic families in Gunfoundry parish, only 17 families owned their own home. Average income per capita was 13 Rupees a day, a Rupee being equivalent then to £ 0.17 – seventeen pence! Of the 829 parishioners, only a third had attended school: 166 primary school, 49 middle school and 47 up to college level. But serious efforts were made to remedy the situation.

Flanking St Joseph’s Cathedral on both sides lay two large Catholic school complexes for boys and girls, accommodating 2000 students each. The vast majority of these were Hindus and Muslims. Catholic children however were given priority admission if they came up to standard.

Catechumen villages

I have paid attention to the established part of the Church in our State, the so-called old villages of high caste Catholics and the city parishes in Telangana. However, when I came to India in the 1960s, the church was involved in a massive expansion programme. Time to recall the situation in Bânigandlapâdu, a typical parish in Warangal diocese.

Parish priest of Bânigandlapâdu in 1976 when I visited the place was Father Govindu Joji, one of my old students, later to become Bishop of Nalgonda diocese. Parish area 264 square miles. Joji looked after 31 outstations in far-flung villages such as Thummalapalem, Jupudi, Kilêspuram, Pâthamulapâdu, Dinakonda, etc. etc.

In all these outstations Joji had to say mass as well as preparing 1000 adult catechumens for baptism. In this he was helped by four religious sisters and nine part-time lay catechists who gave instructions to the catechumens in their villages after work. The sisters also ran a hostel for boys, a primary school and a high school for 450 girls.

When I visited Bânigandlapâdu on 2 January 1976 I helped Father Joji baptise 350 catechumens in Gôpuram village. All of them were ‘outcasts’, that is: they were Mâlas and Madigas, 120 families in total. I remember the day like yesterday.

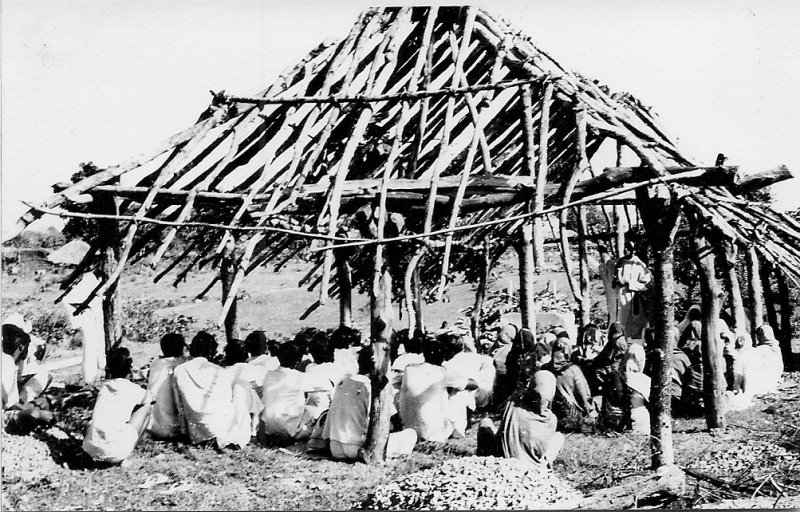

Villagers gathered in front of a typical ‘prayer hut’ which is still under construction.

People had gathered in a clearing near the ‘prayer hut’ of the village. Father Joji gave a final instruction. Then the catechumens were lined up in a huge circle. The first common baptismal prayers were recited. Then Father Joji and I went round to administer the exorcism to each man and woman in person. The sun was rising high in the sky and I was already sweating profusely.

Now the actual baptism started. Joji and I took half a circle each. I was assisted by a mass server who kept bringing up buckets of water. The catechist had stuck a label on the front of each person to indicate the baptismal name they had chosen: Shoury, Chinnappa, Nirmala or whatever. The person would bow his or her head and I would pour water over their head saying in Telugu: “Vimala, or whatever the name was, I baptise you in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit”. If a woman carried a baby on her back, the child too was baptised.

After the concluding rites of baptism, a Eucharist followed during which all went to communion. By the time the whole ceremony had been completed, three hours later, I was totally exhausted and dehydrated. I enjoyed all the more the festivities that followed: the buttermilk, chicken, dancing by the youngsters and tabala music by a Mâla drummer.

John Wijngaards, My Story – My Thoughts, Part Three. MISSION IN INDIA

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage