One of my findings in India that distressed me considerably concerned women. They were obviously repressed, socially as well as culturally. Proverbs will illustrate the point.

A proverb has been called ‘the wit of one person, but the wisdom of many’. Proverbs are brief, rhythmic or melodious expressions of generally accepted values. For the Telugus I found, proverbs contain principles and determine deep-seated convictions of their ‘inner language’. An appropriate proverb would prove a point and even settle an argument.

Among a well-known collection of 8,500 Telugu proverbs[i] I found more than a hundred express judgements about women that are contrary to modern values and Catholic teaching. More disconcerting was the fact that 29 of them could be identified as commonly used even in our Christian communities. Some samples will speak for themselves:

- A boy born is like gold; a girl, dust on the road.

- Even if the child dies in birth, it is better if it is a boy.

- A woman’s assurance is a parcel of water.

- Even if she is the maharaja’s daughter, a woman is subject to her husband.

- A woman is spoiled by going outside the house; a man if he stays at home.

- Leadership by a woman is like sacrifice offered by the sacristan.

- Within her threshold she remains a woman; outside she is a donkey.

- It is better to be born a shrub in the desert than to be born a woman.

The popularity of such proverbs clearly demonstrated a failure to accept the full human and Christian dignity of women.

The root of the problem lay in generally accepted Hindu religious beliefs. I discovered that the Hindu classic on every person’s duties, the Manusamhita, teaches that a woman should always be subject to a man: first to her father, then to her husband, finally to her son. Women cannot pray or sacrifice independently. Their redemption consists solely in faithful servitude to their husbands. Women are by nature fickle, greedy, unreliable and unfaithful. They should be kept at home and under control.

“The faithful wife must constantly worship her husband as a god, even if he be destitute of character or seeking pleasure elsewhere or is devoid of good qualities . . . Women have no sacrifices or fasts ordained for them. Neither are they called upon to perform the şraddhas [= rituals]. Their only duty is to serve and worship their husbands with respect and obedience. By the fulfilment of that duty alone they attain heaven . . . A woman should never think of independence from her father, her husband or her sons . . . When creating women, God allotted to them love of their bed, seat and ornaments. He filled them with passion, anger, dishonesty, malice and bad conduct . . . Woman was created for seducing man and hence there is nothing more detestable than a woman”.[ii]

This was still the generally accepted persuasion of Hindus all over India, in spite of the efforts of the government and enlightened circles to bring about a change.[iii] And what about women in the Catholic Church?

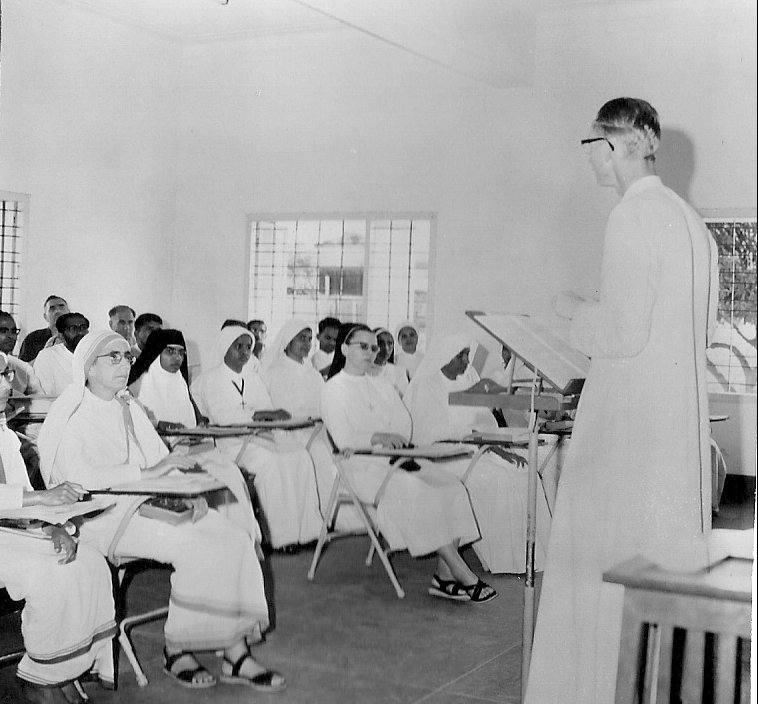

Sisters chatting in the garden during a coffee break

Religious Sisters

The Catholic Church banned women from any participation in the ordained ministries. This was bad enough and in a later chapter I will discuss how I got involved about this in 1975. Here I want to focus on the position of religious sisters, women who had consecrated their life to a more perfect following of Christ in prayer, poverty, celibacy and the service of those in need.

Congregations of religious sisters all over India were running many vital institutions such as schools, clinics, hospitals and homes for the disabled. In Andhra Pradesh alone, at that time, 1800 religious sisters looked after 40 hospitals, 550 schools and colleges, 55 boarding schools for boys and girls, as well as 10 homes for the elderly. The beneficiaries of hospitals and schools were up to 90 per cent non-Christian. And to pre-empt misunderstanding: no attempt was made to ‘convert’ such persons. The aim was simply to help those in need and serve the welfare of people.

But, whereas some religious sisters attended universities and colleges to obtain teaching degrees and medical qualifications, their personal education in faith and spirituality was often woefully inadequate. In one noviciate of a so-called ‘indigenous’ congregation, I found that novices only received two short pep talks a week by the local parish priest. They did not receive any grounding in scripture, theology, spirituality or liturgy. The local staff: superior and novice mistress were ignorant themselves. The situation was not much better in other congregations.

When I was asked to become moderator of the CRI – Conference of Religious in India – for Andhra Pradesh, I saw it as an opportunity. Fortunately, our local CRI was headed by three intelligent and farsighted superiors: Sr Josepha Rachamalli JMJ, Sr Felix Albuquerque SCCG and Sr Amandine Marneni FMM.

With their help I began a programme of systematically urging congregations, especially indigenous congregations and the bishops who supervised them, to send talented young sisters for higher studies in theology, scripture, church law, religious life and other disciplines. It worked. Gradually the Indian noviciates and juniorates began to be staffed by qualified teachers.

But that was long-term planning for the future. It was not enough at the moment. More needed to be done. We had to provide a more thorough formation to the hundreds of young religious who each year emerged from their noviciates.

The answer was a training institute which we called Jeevan Jyothi [= life and light].

Finding premises

Like Amruthavani before it (see my previous chapter on it), Jeevan Jyothi began its life in St. Patrick’s School, Secunderabad. We offered a three-months’ course to a group of 30 young sisters from ten different congregations. They attended talks in a classroom temporarily provided by the school. The lectures were given by qualified priests and religious who at that time worked in the Hyderabad/Secunderabad area: mostly in St John’s Seminary and in a number of religious institutions.

Me teaching a class to a group of sisters, with some men in the audience too

For years I myself and the CRI committee looked for a better and more permanent place to house our new institute. Nothing suitable was for sale. Till in the end we located a promising house in Begumpet. The house was spacious. Moreover it was surrounded by a large garden that offered the possibility of future expansion. The property was for sale for a number of reasons, I learned. Partly because, at the time, it lay close to swamps which created the enduring nuisance of mosquitoes.

Acquiring the house proved problematic. It was jointly owned by a number of persons. But, as luck would have it, the chief owner was delighted to discover who was interested in buying. Not only did he owe gratitude to sisters for having helped in his education. He also made a special request – which he communicated only to me, not to the other members of the committee.

In a somewhat hush-hush encounter which alarmed me at first, he explained that one of his cousins in Germany required medical help. “She needs a bye-pass operation for her heart”, he told me. Bye-pass operations were rare at the time, and expensive.

“If I and my partners sell the house in Begumpet to the CRI”, he asked me, “can you find a Christian Charity in Europe that would help pay for the operation?”

I was worried. I knew that Indian custom regulations at the time did not allow Indian citizens to make sizeable payments abroad, outside India. Transferring money abroad was not allowed. Would we take part in an illegal transaction?

I told him that I would get advice from a lawyer.

The advice I received was this: “You are walking in unchartered territory here . . . But if the sale of the house in India, is not – in legal terms – linked to the charitable donation given outside India, you are not breaking any law. It is clear that you are allowed to help a friend . . .”

I also consulted possible donors in Europe – and succeeded to get a positive response. After all, in Europe too religious congregations run clinics and hospitals, often the best in their country, and they were only too happy to help religious in India achieve a good education.

It led to a second meeting with the owner.

He agreed to sell the house to the CRI without making the charitable donation to his cousin in any way a legal condition of the sale. “As long as you promise me on your word as a Christian priest that my cousin will be helped.”

He agreed to sell the house to the CRI without making the charitable donation to his cousin in any way a legal condition of the sale. “As long as you promise me on your word as a Christian priest that my cousin will be helped.”

And that is how it was done. I stress again that the CRI committee was not aware of the background complication. They were pleased with the new location and, over time, new buildings were added to provide accommodation to many generations of young sisters.

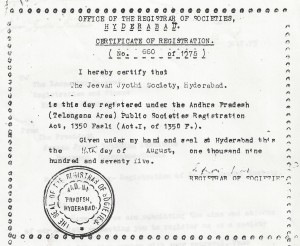

On the 16th of August 1975 Jeevan Jyothi was formally registered as a charitable society in Andhra Pradesh.

But what about its teaching staff?

Recruiting resident lecturers

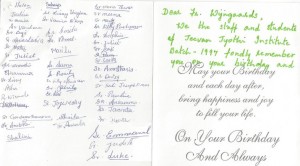

A birthday card from the batch of sisters studying in 1997

Jeevan Jyothi began to offer annual formation to groups of 50 sisters. ‘Annual’ meant that the course lasted for ten months. This was brilliant but by lack of resident teaching staff, the temptation was to resort to a system of ‘block courses’: that is courses by specialized teachers who often came from other parts of India to present short intensive lectures on one topic or another. Two weeks scripture (the letters of St. Paul), one week theology (christology), one week liturgy (the eucharist), two weeks church history (the reformation), etc. etc.

Though such ‘block courses could have advantages if used judiciously – for instance, to introduce the students to exceptional experts, they could not form the substance of a thorough teaching programme. For the ‘block courses’ acted like short intensive bursts of information that could not be properly digested by the students. New insights are easily forgotten by a succession of ever new topics. Real growth in understanding requires a gradual, long-term exposure to systematic teaching.

Moreover, the ‘block courses’ tended by their very nature to be brief, compressed and generalised introductions. For some of the students they were repetitions of what they had already heard. I felt that good theological/scriptural/spiritual teaching at Jeevan Jyothi’s level should focus on select topics which were thoroughly explored and deepened out, rather than superficial, general introductions.

Teachers of ‘block courses’ invariably found that the time given to them for their lectures was too short to do justice to their material. They would therefore either cram heavily compressed teaching into hour after hour of lecturing, or resign themselves to a half-hearted, simplified presentation. As for the students, four lectures on the same topic each day for six days on end would prove far too heavy and congested. The ‘block’ system in fact deprived students of the time for private study and weakened their motivation to pursue any topic in depth. But that was wrong. New knowledge acquired during lectures should be assimilated by the students through personal reading, library research, preparing essays and expressing their views in carefully tailored personal assessments (exams).

You see from what I am writing that I felt strongly about this. I knew from my own teaching in St John’s Seminary that students need time, often many months, before grasping complex issues, such as the function of ‘literary forms’ in a correct understanding of scriptural texts. In the ‘block course’ system, the needs of the students or the requirements of this level of studies were not sufficiently taken into account.

However, the problem Jeevan Jyothi was facing lay in the lack of trained staff. At the time there was almost not a single religious sister in the whole of India qualified in ecclesiastical studies, such as theology, sacred scripture, church history or whatever. So I made up my mind to recruit such staff from abroad.

In the summer of 1974, during a short break in the Netherlands, I appealed to the national conference of religious. I also visited the headquarters of individual Dutch congregations. In the end I managed to obtain the services of two very capable sisters, both doctors in theology: Dr Sr Angela Nijssen of the Sisters of Charity of Tilburg and Dr Sr Gabriel van den Heuvel of the Sisters of Charity of Schijndel.

Sr Gabriel became the dean of studies, Sr Angela principal professor of theology. With the help of some lecturers from St John’s Seminary, they could offer full one-year’s academic courses to the students.

Religious power house

As I am writing this down, fifty years later, I believe that more than 1600 sisters followed the one-year course. The need for the institution diminished somewhat though the years on account of many religious congregations, over time, acquiring their own trained theologians so that formation programmes in their own noviciates and juniorates improved.

Many other religious benefitted from shorter renewal courses. In later years the CRI of Andhra Pradesh also built a retreat house in the Jeevan Jyothi property which has been much in demand.

[i] V. Satyanarayana, Telugu Sametalu (Hyderabad, 1965).

[ii] Manusamhita, V, nos. 154, 156, 184-9 (ed. Nirnayasgar Press, 1933); cf. K. M. Kapadia, Marriage and Family in India (Bombay, 1966), pp. 255-72.

[iii] Rakshan Saran, ‘The Status of Women’: Encyclopaedia of Social Work in India (Government Publication, Vol. II, New Delhi, 1970), pp. 366-75.

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage