On the day I was ordained a priest I was given my first assignment. I was to do higher studies in Rome in order to obtain a doctorate in dogmatic theology and a licentiate (MA) in sacred scripture. So in September 1959 I reported for duty in the house for Mill Hill university students which was situated in Monteverde Vecchio not far from Trastevere in central Rome.

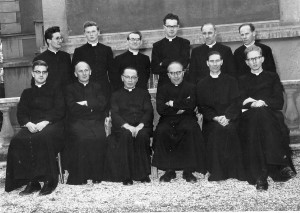

Our community of staff and students in Rome. I am sitting on the right. Martin Fleischman two seats left from me.

There were eight of us studying various branches of theology. Frugal Father Martin Fleischmann, Procurator General of Mill Hill Society, was our rector. Our house was actually an old villa that was surrounded on all sides by a lush garden. Its location could not have been better. In theory we could travel to the centre of town by bus. But boarding a crowded Roman bus turned out to invariably involve elbowing one’s way in. Italians do not wait in polite queues. It runs counter to Italian impetuosity, I was told. Impatient hordes would cluster round each bus terminal, all intent on boarding the next bus before anyone else. It proved a nightmare. I often stood, defeated, with one bus after the other carrying off triumphant Romans leaving me and some other stragglers behind. So I decided to find independent transport through Rome – which became possible when a Christmas gift from my parents in the Netherlands enabled me to buy a bicycle.

Anyway, let me go back to the beginning. On arrival, Fleischmann gave me to understand that I was to register next day at the Gregorian University in the Piazza Pilotta. My first aim was to acquire the licentiate of theology within one year, bypassing the normal course of four years. This was in consideration of the fact that I had already studied four years of theology in Mill Hill College London. Gregorian authorities agreed but on condition that I pass a one-hour’s oral theological entrance exam. I said: OK. I was told to report for this the week after. The whole procedure was to be conducted in Latin which was the official language of the Gregorian at the time. It came as a shock.

I had studied a fair amount of Latin in my high school days, it is true, and in Mill Hill College we had used Latin textbooks for theology though lectures had always been given in English. Never had I been lectured to in Latin nor had I ever myself spoken Latin.

On the appointed day I found that the hour consisted of four fifteen-minutes’ oral exams taken by four different professors, each testing my knowledge of a different aspect of theology. I spluttered, I stumbled, I often groped for the right Latin words but to my immense relief: I passed.

Thinking back of this gives me even greater satisfaction since I came to know that the talented Karol Wojtyla, the later Pope John Paul II, failed a similar entrance exam at the Gregorian in 1946 which made him join the nearby Angelicum University instead. On reflection, this may precisely have proved his downfall as a theologian. For he missed the more modern and critical approach to theology taught by the Jesuits of the Gregorian in exchange for the antiquated Thomist approach still favoured by the Dominicans of the Angelicum. If he had studied at the Gregorian, God knows, he might have been less stuck in medieval thought, more open to today’s world . . . causing huge setbacks to the universal Church. Which takes me straight to the heart of the matter.

Scriptural carnage

In today’s Catholic Church ancient and modern ideas clash, turning the study of theology into a battlefield. And the interpretation of sacred scripture stands right at the centre of the conflict.

When I began my spell in Rome’s universities in 1959, the scriptural battle which had already gone on for centuries, was coming to a head. And scripture was the main focus of my own studies. So I found myself in the midst of the raging battle on how scripture should be understood.

What was at stake?

In the sixteenth century the astronomer Copernicus had begun to show that it is not the sun that moves around the earth, but the earth that encircles the sun. Theologians rejected this finding as heretical because, they said, ‘it goes against the inspired Scriptures’. Matthew 5,45 was one text quoted to prove this claim. For Jesus says: ‘The Father makes the sun rise over good and bad alike.’ Therefore, it is the sun that moves and not the earth, they said. Moreover Joshua 10,12-15 relates a miraculous event in which ‘the sun stood still’. When Galileo Galilei proved that Copericus had been right, the Holy Office ordered him in 1633 to retract his belief that the earth circles round the sun, and condemned him to house arrest till the end of his life.

Other conflicts developed during the 19th century. The Gospels were shown to be full of internal contradictions. Take the accounts of the Last Supper. Matthew 26,28 states that Jesus handed the chalice with wine to the apostles saying: ‘this is my blood of the covenant that will be shed for many for the forgiveness of sins’. Luke 22,20, however, reports that Jesus said: ‘This cup is the new covenant in my blood which was shed for you’. Since this refers to one single, specific occasion, which of the two is right? And what about such fantastic stories as the devil hauling Jesus up onto the pinnacles of the Temple, or Peter catching a fish with a shekel in its mouth? Friedrich Strauss’s The Life of Jesus (1835) dismissed most of the Gospel as mere myths. And it did not stop there.

Analysis of geological layers established beyond doubt that the earth must be millions of years old. Biologists such as Charles Darwin postulated a gradual evolution of species (1859). But this contradicted texts such as Genesis 1,1-31 and Exodus 20,11 which assert that ‘in six days Yahweh created the heavens and the earth and the sea and all that they hold’.

The reaction of Christians is well known. Many refused to accept the findings of science. Others looked for harmonizing explanations. The creation in six days, for example, was explained as a creation in six periods. Desperate efforts were made to fit various scientific discoveries into the appropriate period of creation. The approach is still popular among creationists today.

The Jesuit scholar George Tyrrell (1861-1909) stood out among the theologians who attempted to solve the conflict between traditional faith and modern science. He sponsored a scientific method of examining Christian sources. Catholics should be ‘more open’ to modern society, he urged. He argued that the Church’s response to the religious problems of the modern age could not be simply to reiterate Christian dogmas which had been formulated in the thirteenth century. He held that the externals of the Church, like its laws and customs, needed to be trimmed to fit the religious culture of modern times and that Scripture too needed to be interpreted in a new way.

“Each age has the right to adjust the historico-philosophical expression of Christianity to contemporary certainties, and thus to put an end to this utterly needless conflict between faith and science which is a mere theological bogey.”[1]

Among theses condemned by Pius X in Lamentabili Sane Exitu we find:

“If an exegete wishes to apply himself usefully to Biblical studies, he must first put aside all preconceived opinions about the supernatural origin of Sacred Scripture and interpret it the same as any other merely human document.”

But the Pope was wrong. To interpret scripture correctly, we first have to understand it accurately as human literature.

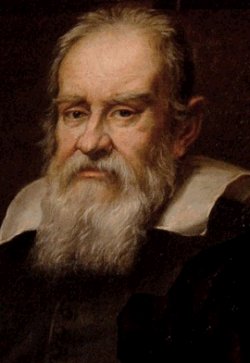

Galileo Galilei

Scholars began to look at scripture with new eyes. How should its texts be read? Galileo Galilei had already pointed the way with the observation that scriptural teaching is limited to what it says about God and salvation. In presentation it adapts itself to how people popularly see things.

“With regard to the standing still or the movement of the sun and earth, the inspired Scriptures must obviously adapt themselves to the understanding of the people and this is what they achieve through the chosen expression, as experience shows. Even today the ordinary people, though they are no longer so uneducated, still have the same idea. To change the people from this idea would be a waste of time since the people cannot understand the arguments against it. Even if the immovable sky and the moving earth had been proved with certainty for the scholars, one would have to express themselves differently for the crowd. If you were to ask a thousand people, one would hardly hear from one the reply that he believes the earth moves and the sun stands still.”[2]

But this was not the full explanation. After many false attempts, the liberating insight proved to be quite simple: sacred scripture is written language, is literature, and should be read as any other literature. And literature is governed by literary forms.

You cannot read a newspaper properly, for example, without distinguishing its literary forms. You know that the headline on the front page: ‘Beauty Queen bares her pitch black skin’ reports a fact. An article somewhere more central in the paper bears the caption: ‘How to save the nation from skin cancer.’ You realise it expresses an opinion. Down the page a smiling girl declares: ‘Cranbury Cream cleared my face of pimples’! You recognise it to be an advertisement. You dismiss a strip story showing an alien putting on a human skin as pure fiction.

Understanding each of these scraps of text, we simply need to know their ‘literary form’: news item? ad? editorial? and so on. The same applies to Sacred Scripture. More about this later. For I began to realise that Scripture study does not only consist of exegesis, draw the right meaning from the original text, it also needs hermeneutics, that is: an interpretation that makes sense to the ordinary people for whom Scripture was written.

God’s people in Rome

I was determined not to lose myself totally in dusty academic libraries. I knew I was a priest, and priests are ordained for people. After a few months I had picked up enough Italian to start looking for priestly work in Rome at evenings and during weekends.

The situation of the Catholic community in Rome was actually shocking. The population of the Roman suburbs had already slid into the mood of secularist indifference that now holds the whole of Europe in its grip. I scouted around and accepted a job as part-time assistant priest in the parish of Saints Francis and Catherine in Monteverde Nuovo. The church was popularly known as the Due Patroni, in view of the fact that Francis of Assisi and Catherine of Siena are the two patron saints of Italy.

Our parish was entrusted with the spiritual care of well over 20,000 people, 90 % of whom were supposed to be Catholic. In fact, you would get a standard answer if you asked anyone, as I did a strikingly hansom young man who cut my hair in the local hairdressers:

“Are you a Catholic?”

“Si, Padre. Cattolicissimo!” — Yes, Father. I’m very Catholic!”

Such a reply did not mean he had visited church since his first communion. Of our hordes of nominal Catholics, hardly 1500 visited our church on Sundays, even though missing Sunday mass was still officially listed as a mortal sin. The state of alienation from the Church may also be judged from the circumstance that hardly one in a hundred persons who died would receive the last sacraments. Rather than calling a priest to help a dying person make peace with God, they would rather wait for him or her to die, then pay two nuns to spend a night in prayer at the deceased person’s bedside, as a superstitious remedy. For superstition flourished.

Our parish priest found a man on his knees before the statue of Our Lady. He had lit seven candles and was saying the rosary seven times, he told the priest. And he had started punctually at seven in the morning. He was convinced this would secure his passage to heaven. When the man had left, the PP realized that day was the 7th of July, therefore: the seventh day of the seventh month.

My main job consisted in celebrating mass for the congregation at 10 o’clock, and hearing confessions during the 8, 9, 11 and 12 o’clock masses. Every hour another mass with a new congregation. And, since this was before the liturgical reforms, some of these masses were for weddings, others for funerals, as the moment demanded. The change-over from one kind of mass to another was stage managed by a team of efficient sacristans.

I vividly remember an occasion when the 11 o’clock mass had been a funeral. The altar had been draped in inky silk ribbons. Black banners were slung from the columns behind the altar. The deceased lay in her open coffin, flanked by tall dark candlesticks and bouquets of white lilies. Because the funeral cortege had arrived late, the mass ran over time. The priest, predictably wearing a pitch black chasuble, was still incensing the body and praying the final commendation when, suddenly, a wedding procession stood at the main door to enter for the noon-time mass . . . I held my breath.

Brilliant Italian improvisation sprang into action. The coffin was quickly sealed and, with the principal mourners, deftly conducted out of sight via a side door. The black decorations everywhere came down as by magic. The soot-coloured mat down the main aisle was folded up, while a crimson carpet was rolled out. Vases with explosions of red, yellow and pink flowers appeared as from nowhere. In five minutes flat, a scene of somber mourning had been transformed into the flamboyant setting for a wedding.

During Easter time, all priests of the parish were expected to take part in the traditional blessing of homes. I too took part. I got a mass server assigned to me who carried a small bucket with holy water. I was dressed in cassock and a white cotta, holding a sprinkler in my hand. We walked to the apartment buildings, the palazzi as people called them. In each building we would take the lift to the sixth of seventh floor and then work our way down. Four apartments would open out on each landing. The server would ring each doorbell and most people would invite us in, anxious to have the Easter blessing. But while I sprinkled room after room with holy water, they would simply continue doing what they had been doing before. I might as well have been a window cleaner. Only a few might kneel down and make the sign of the cross as I passed. In spite of the midday hour some were still in bed. I recall sprinkling a bedroom with a young couple wriggling and giggling naked under their bed sheets. How appropriate in Easter time I thought.

After obtaining the licentiate in theology in 1960, I attended the Pontifical Biblical Institute for two years which resulted in my acquiring the licentiate in Scripture. Then I returned to the Gregorian to obtain a theological doctorate with a dissertation based on Scripture.[3]

[1] George Tyrrell, External Religion. Its Use and Abuse, Sands & Co, London 1899.

[2] Galileo Galilei, in a letter to Duchess Christina of Lotheringia, 1615; Briefe zur Weltgeschichte, ed. Karl Heinrich Peter, Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag 1964, pp. 80-82; my translation.

[3] My dissertation resulted in a number of publications: J.N.M. Wijngaards, The Formulas of the Deuteronomic Creed, Tilburg 1963; Vazal van Jahweh, Bosch & Keunig, Baarn 1965; The Dramatization of Salvific History in the Deuteronomic Schools, Brill, Leiden 1969; Deuteronomium uit de grondtekst vertaald en uitgelegd, Romen & Zonen, Roermond 1971.

John Wijngaards, My Story – My Thoughts, Training for battle

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage