The last four years of my training for the priesthood took place in Mill Hill in North West London. Our theological college on a hill overlooked beautiful grounds. The building itself was composed of an old and a new section: to the 19th century cluster of monastic cloister, chapel and tower had been joined a postwar businesslike wing that contained floor above floor of student accommodation. This mixture of old and new curiously ran parallel to the ancient and modern strands in our formation programme.

What does it mean to be a priest today?

In the Middle Ages hierarchy and monastic scholarship had sculpted an image of the Catholic priest based on temple cult. A priest was a sacerdos, a consecrated functionary handling sacred objects and mediating at sacred events. A good priest was the person who could radiate God’s otherness to people entrusted to his flock. His duties consisted mainly in presiding over the Eucharist, preaching at Mass, administering baptism, hearing confessions and blessing marriages. However much a priest might wander from the parish church to visit families in their homes, he would always gravitate back to the hallowed spaces of the sanctuary, the confessional, the sacristy. The peak moments in his life were the recital of the prayers found in his breviary, his visit to the Blessed Sacrament, his punctual daily examination of conscience.

Some of our college staff still held out such a medieval ideal of the priesthood. For them the priest was anointed, pure, set apart. Texts were quoted at us from Cardinal Herbert Vaughan’s The Young Priest or from Cardinal James Gibbons’ Faith of Our Fathers: “To the carnal eye a priest appears like another mortal. To the eye of faith he is exalted above the angels”. Presenting heavenly values to earthly people as a priest does, he should dress in black and stay out of pubs, workshops and picket lines.

But times were changing. A more dynamic ideal of the priesthood appealed to us students. And it had a biblical foundation. What else had been in Jesus’ mind when he sent apostles to proclaim the Good News? Had he set them apart to offer sacrifices to a worship-loving God as cultic ministers? Or did he not rather commission them to gather stray sheep and assemble a community that could usher in the new kingdom? Where should their hearts be: in the crowded turbulent homes of people – or in the sanctuary?

I knew I had been called to be a priest ‘for others’. For me the priest had to be a son of man like Jesus had been: someone who mixed with publicans and sinners, someone vulnerable enough to need the support of friends, someone finding encouragement in the way the Father reveals himself to ordinary men and women. I was set to live out a people-oriented priesthood, focussing on people’s problems and speaking their language. The priest was a sacrament, of course, a visible sign of God’s love. But sacraments are for people, as the ancient adage reminded us – and as living models of the priesthood made clear.

My priestly heroes

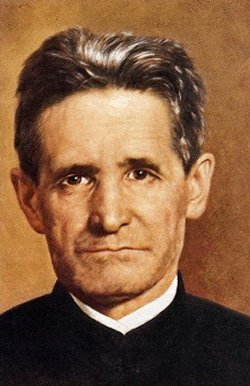

A priest who spoke to my heart was Rupert Mayer. He had acquired lasting fame as one of the earliest and most outspoken opponents of Hitler. He spent nine years in prison for his damning of Nazism: “No Catholic may ever be a Nazi!”, he kept saying. But that was not the main reason why thousands of Germans kept visiting his shrine in the crypt of St Michael’s Church at Munich. He was a priest who won people’s hearts because he went to meet them where they were.

Father Joseph Mayer. Munich

As chaplain to the Eighth Bavarian Division during World War I, he could have opted for safety, well behind the lines. Instead he stayed in the trenches, crawling from one outpost to the other, heartening the living and comforting the dying. We can imagine what that means when we learn that his division was decimated in 1916 during the battle of the Somme. The particular battalion he served was reduced from 900 troops to 220 in eight days. Of the new strength of 770 troops with which the battalion was hastily reinforced, 650 became casualties in the next week. The official despatch reads: “Throughout these devastating attacks from 20 July to 13 August, one man stayed put in the front line: Padre Mayer. Under withering artillery fire he saved many lives by giving first aid and by carrying the wounded to safety.” Having earned three military distinctions and the Iron Cross in two years of service, he lost his left leg when shrapnel shredded his knee.

The collapse of Germany after the war was almost as dreadful an experience as the war itself: disruption of families, unemployment, poverty, political confusion everywhere. Rupert Mayer, now limping parish priest of St. Michael’s in Munich, proved once more his closeness to the people. He visited the sick and the poor, organized the men in a strong Marian sodality and joined political rallies in the tumultuous Bierhallen. It was here that he challenged first the Communists, then Hitler and his associates. Repeatedly he was shouted down. On one occasion a bully kicked against his wooden leg and sent him sprawling to the ground. But, whether friend or foe, people knew that here was a priest who spoke their language and cared for them.

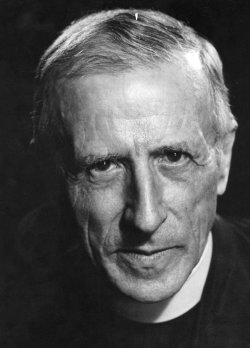

Then there was Teilhard de Chardin who had also served in the First World War. Teilhard was French. As a stretcher-bearer in the 8th Moroccan Rifles he was constantly in the midst of enemy fire comforting and rescuing the wounded. For his courage he was awarded the Médaille militaire and the Legion d’Honneur.

Father Teilhard de Chardin, Paris

Teilhard became a Jesuit scholar who combined expert knowledge of paleontology with profound present-day mysticism. His name as a scientist was secured when during one of his many geological expeditions to China, he was involved in the excavations at the so-called Peking Man site of Zhoukoudian, near Beijing. Teilhard helped establish that Peking Man belonged to the species of hominids called Homo Erectus and dated more than half a million years ago.

Next to his long and fruitful academic work, Teilhard also developed a revolutionary approach to understanding the evolution of human beings. In the seminary, I was thrilled reading his books such as The Phenomenon of Man, The Divine Milieu and Hymn of the Universe. Teilhard was a different kind of priest than Karl Mayer and, yet, he too was a hands-on spiritual leader, not a sanctuary-hugging thurible-swinging cult man. And this is what I liked about real priests, as I called them. They could not be put into a narrow mould. They responded to the needs of the Catholic community in exciting unexpected ways.

Mayer had been persecuted by the Nazis. Teilhard faced other enemies: conservative theologians in the Vatican. His writings were censured. He was forbidden to publish some of his best work during his life time. Fortunately friends published them for him after his death. It prepared me for the opposition a dedicated priest might face from even within his own Catholic community. And as I am writing these lines, the warnings against Teilhard’s thinking are still not fully lifted by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

Priests for people

The academic courses we studied at Mill Hill College – theology, sacred scripture, liturgy – were woefully substandard. Fr Duivestein (‘Duivy’ in students’ parlance) entertained us with lengthy lectures on angels: Do they have wings? Are cherubim different from seraphim? Do they rank higher than human beings, but then: what about Christ? And so on. It so happened that the statue of a guardian angel along the lane leading to the entrance of the college was accidentally damaged – below the angel’s belt – by a passing car. Immediately a rumour did the rounds: “Duivy is delighted. He can now verify for himself whether angels are male or female!”

Only moral theology and church law stood out under the tuition of Fr Serafino Masarei. We were not aiming at becoming scholars, however. We wanted to set the world ablaze with the revolutionary vision brought by Christ. So a number of us looked around to supplement our formation with other energetic teachers.

One such person was Father Bernard Bassett who had been a chaplain to the Royal Air Force. He dreamt of transforming a passive laity into vigorous apostolic teams. So he founded the Cell Movement which consisted of a wide network of laypeople connected mainly through the telephone. The network could trigger national campaigns, such as making hundreds write to newspapers to support Christian values when moral issues were debated. The network also initiated the push to ‘Put Christ Back into Christmas’ and helped Britain focus on fairness to the Third World.

I read a number of Fr Basset’s books – Priest in the Piazza, Seven Deadly Virtues – and attended his courses in the centre of London. In one talk to seminarians he spoke these memorable words:

Whatever you become as a priest, don’t be a wimp. Christ’s cause is not served by weak and spineless cowards. Stand with both legs firmly on today’s ground and be prepared to wade through the muck and mud of real life.

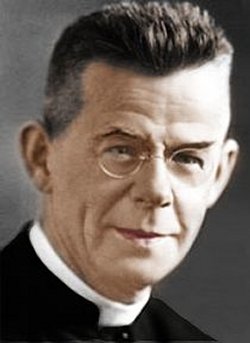

Father Joseph Cardijn, Brussels

I also admired the Flemish priest Joseph Cardijn. Hailing from a working class family himself, he was moved by the struggles of the men and women who toiled in Brussels’ sprawling industrial estates. He saw that these workers needed to liberate themselves from their degrading circumstances through their own action. The trade unions usually failed because they did not address the root problems and ignored Christian principles. So he founded the Young Christian Workers (YCW).

Bringing groups of workers together he taught them the method of ‘see, judge and act’. Seeing required becoming aware of the facts. The group had to judge these facts according to Christian principles of justice for all. They then had to decide on a concerted plan of action. The YCW soon grew out into a vast and influential movement that formed generations of Christian leaders.

As Cardijn told priests in 1951:

“It isn’t enough to preach to laypeople. The priest must go further . . . He must help, encourage and guide them . . . The priest must develop a profound sense of this responsibility, as well as the qualities which are needed to put it into action: human capabilities, fraternal love, a vision of the world and of the Church, boldness, courage, perseverance. A great many socialists, communists and other militants who set up human messianic movements are to be admired for their deep sense of responsibility, their strong will and their steadfastness and toughness in action.”

A small of group of us set up a ‘task force’ among the students in Mill Hill College with the explicit objective of seeing to it that the apostolate of the laity would be introduced to all the missionary areas to which we might be sent. We studied the training programmes conducted by the YCW in London. We followed with interest the reports of ‘extension workers’ sent by the YCW to third world countries to start the movement there.

On one occasion one such extension worker, on return from East Africa, held an important briefing session in the middle of London. We knew it would be crucial for us to attend that meeting. So, in spite of a clash with our strict college rules and without the necessary permissions, I and another student travelled to London and shared in the event. We returned back to Mill Hill College without our absence having been spotted by the authorities. If they had found out, it could have led to our expulsion from the College. We were serious indeed.

When Cardinal William Godfrey, Archbishop of Westminster, laid hands on me and twenty-seven of my classmates on a sweltering day in June 1959, he may not have realised what ‘troublesome priests’ some of us might become.

I for one did not intend to be an institutional priest irrevocably chained to medieval structures, a member of a male mandarin caste. I sought to be a priest for people. I wanted as a leader to further the unusual dimensions of God’s kingdom: love without profit; seeking peace instead of securing power; conquering fear by hope; reaching out to endless horizons in prayer. I wanted to make people see with new eyes, spell out and evoke the deeper, spiritual meaning of reality. I wanted to interpret mystical realities and transform them into real life, to heal, dispense God’s Spirit, celebrate God’s presence. I was set to defy convention, as another Christ here and now, a Christ for people.

John Wijngaards, My Story – My Thoughts, What kind of priest?

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage