Before I could trace the Octopus to its spawning ground, I found out the hard way that it operated under Church protection; and that it was the poorest of the poor who suffered most.

Next to my teaching in the seminary I tried to do as much pastoral work among ordinary people as I could. On Sundays I would often celebrate mass in Telugu for the parishioners of Ramanthapur, a small village, or rather a cluster of slums, surrounding the seminary. This brought me in touch with Mary and Joseph.

Joseph was a carpenter. He was a Hindu of low-caste origin who applied for baptism because he wanted to marry Mary who was a Catholic. I was involved to some extent in the preliminary instruction, and later in his baptism itself. They were gentle, unassuming people, genuinely lost in a harsh world. I could not help seeing in them an Indian incarnation of the Holy Family . . . They would have jumped at a stable for accommodation!

The hut Joseph and Mary lived in was even smaller than this . . .

I visited them in their tiny mud-wall hut in Ramnagar. Like other poor people, they lived in the shadow of a Parsi Tower of Silence. This burial tower was a two-storey hollow building covered with a lattice of iron bars instead of a roof. As you may know, Parsis believe that human bodies should neither be interred nor cremated. They deposit the naked corpses of their dead on the roof trellis so that birds of prey can pick off the flesh and the bones fall down into the pit below. The whole area around the Ramnagar Tower of Silence stank. Mary and Joseph lived in a place normal people would shun as hygienically and religiously unclean.

As I crept into the hut I found Mary her latest child. She was a girl. A two-year old elder brother, was sitting on the dust floor looking at me with large inquiring eyes. I was offered a mug of tea. Joseph told me he had a temporary job on a building plot. Mary narrated that she had paid a visit to her parents’ home in a country village.

“I wasn’t welcome”, she said with tears in her eyes. “I wasn’t welcome in the home I grew up in. When I approached the house, I overheard my mother say to the others: ‘I hope that’s not Mary who is coming. For God’s sake! What can I give her to eat?!’ . . .”

“My mother has had seven children”, she added by way of explanation. “My father died.”

I did not know what to say.

Then she said to be again: “Look where we live. Joseph is not getting a proper wage. They take advantage of him. How can we survive?”

And with a weary look on her face: “Father, in my whole life I have never known comfort.” Her literal words in Telugu were: “Nâ jîvithamulô sukham thêlêdhu”. I will never forget. These words still ring in my ears after so many years. I hear them as a reproach when I enjoy comfort myself. I wish I could have done more of them.

I was called out to Osmania General Hospital in Hyderabad some time later. Mary and Joseph’s third child was dying. I found them in the emergency clinic for children, standing helplessly near a cot where the baby lay linked to a life-support machine. Its emaciated body was still breathing. Dysentery, I was told. I prayed over the baby. It died soon afterwards.

A major problem compounding abject misery in India was the number of children born to poor parents. It did not give undernourished mothers time to recover from the hardships of childbirth. It added to the burden of feeding and clothing a family in spite of insufficient income. As the Government of India recognized, family planning was essential to help the poor rise above starvation level. But what support did the Church have to offer?

Lightning from a clear sky

In early July 1968 a letter arrived from the apostolic nuntiature for Fr Eddy Bennett, our lecturer in moral theology and church law. Eddy was away for some weeks on a lecture tour in Jabalpur in the north of India. He had asked me to open his post, and reply to any message requiring an immediate response. The letter contained a bomb shell. It gave advance warning to church lawyers of the new instructions contained in Pope Paul VI’s Encyclical Humanae Vitae.

We were all aware that a papal commission of experts had, for a number of years, been studying the question of artificial birth control. The signs had been positive. It looked as if Rome would soften its stand against contraceptives. The opposite happened. In spite of the commission recommending [with a majority of 68 to 4!] that Catholic couples should be allowed to, responsibly, decide for themselves about methods employed in planning their families, the Pope condemned all artificial means:

“ . . . any action which either before, at the moment of, or after sexual intercourse, is specifically intended to prevent procreation—whether as an end or as a means . . . It is never lawful, even for the gravest reasons, to intend directly something which of its very nature contradicts the moral order, and which must therefore be judged unworthy of man, even though the intention is to protect or promote the welfare of an individual, of a family or of society in general. Consequently, it is a serious error to think that a whole married life of otherwise normal relations can justify sexual intercourse which is deliberately contraceptive and so intrinsically wrong.”[i]

This meant that people like Joseph and Mary were forbidden to avail themselves of a condom or an IUD (intra-uterine device) provided by the government. So were the other one third of the population, 200 million at the time, who lived under the poverty line! The Octopus had won. He got Pope on his side!

The initial reaction in India was pandemonium. Many priests refused to continue hearing confessions, saying they could not follow the Pope’s guidance. The fog cleared somewhat when at least ten national bishops’ conferences declared that, in spite of the Pope’s words, couples could follow their own consciences and that confessors should respect such decisions. The bishops who stood up against the Pope were Austria, Belgium, Canada, East Germany, France, Indonesia, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, Switzerland and West Germany. Their position was supported by prominent theologians such as Karl Rahner and Bernard Häring. Unfortunately, the Indian bishops were undecided.

I entered the fray by publishing letters in the Catholic weekly The New Leader. I reminded Catholics that papal encyclicals are not infallible. Had Pope Pius XII not written in Humani Generis (1950): “In writing encyclicals, it is true, the popes do not exercise their teaching to the full”? I was promptly attacked by traditionalists. Father A Gomes of Goa said I misinterpreted the Latin. “The phrase regarding the limited teaching value of encyclicals should be read as the subjective opinion of a possible opponent”. According to Gomes, Pope Pius XII stated that, though some persons assume popes do not teach infallibly in encyclicals, they claim full assent of mind and will. In other words: they are infallible in practice.[ii]

I am quoting this to show how a question of life or death for ordinary people like Joseph and Mary was now deteriorating into squabbles about the authority of encyclicals . . .

The next time I visited Joseph and Mary they had moved to the Victoria Leprosy Hospital in Dichpalli, hundreds of miles north of Hyderabad. Joseph had been found to be infected by leprosy. He was treated in Dichpalli as an outdoor patient. With Mary and children he had been given a hut to live in on the hospital grounds – grandiose accommodation compared to their previous home in Ramnagar. The hospital employed him as a carpenter in their workshop where he fashioned crutches for other patients. Mary and Joseph were reasonably happy in spite of the threat of having to leave the premises once he had fully recovered. If ever there were underdogs, this ‘holy family’ was one of them! Victims to fate and also to the Octopus.

Imprisoned in a mental cage

One year, returning from a short visit to my parents in the Netherlands, I had a strange encounter. My flight arrived late at night in Bombay at the old international airport. Because the connecting flight to Hyderabad would depart only early next morning I was doomed to spend the night in the airport itself.

It was far from comfortable I assure you. Apart from the toilets, no facilities were open: no tea stalls, no coffee bars, certainly no restaurants. With a few other passengers who had to wait like me, I found myself in a large concrete shed with hard wooden benches to sit on. I walked up and down a couple of times and then found a seat on a bench somewhat removed from the others. I was the only foreigner.

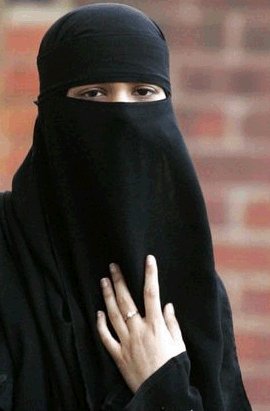

Muslim girl wearing a burka

A young Muslim woman, wearing a burkha, her face only showing two eyes peering through a veil, walked up from the other side of the hall and sat down, with her back towards me, on a bench close by. Then she began to speak in immaculate English. I supposed she had guessed I was a missionary.

“Don’t look in my direction”, she said in a low voice, “It might arouse suspicion.”

I was intrigued. “Who are you?”, I asked. “Are you travelling to Hyderabad?”

“Yes”, she said.

She told me her story. She came from a Muslim family in Hyderabad. She had studied in a Christian school. When she was 17, she had been married off to a businessman in Dubai. Now she was on a short vacation to visit her family.

“What is it like? In Dubai I mean?”

“Oh, it’s OK. My husband and the older wives are treating me well. I have friends, other women from India, who come to see me at times. We go shopping together, always with a servant of course. I have a son. My husband will give him a good education . . .”

She stood up and walked away again. Till this day I still don’t know what she was really trying to tell me. Being an intelligent woman she probably realized she was living in a social and religious cage. Because she had accepted it, she was living in her own mental cage too. Was she trying to step out?

On reflection I realized that Hindus too were constrained by the cultural and mental cages they lived in. Like the two wives of our local mason in Ramanthapur. Parents often find it difficult to arrange a marriage for their daughters because it requires paying for the dowry brides have to bring with them. The father of the twin sisters who married the mason, after negotiation, only needed to produce one dowry.

What did the twin brides think about their situation? The Indian Hindu Marriage Act of 1955 had, 15 years earlier, made polygamy illegal for Hindus and Christians, but I doubt whether the twins were aware of it. They were caught in a system and accepted the consequences. Their husband, the mason, was a kind man and had a good job. So what more could they want? They were prisoners of the cultural code engraved in their minds. But there were exceptions – such as the Hindu saint Mahadeviyakka.

Jumping out of your cage

Akka Mahadevi was an Indian mystic who lived during the 12th century in the India State of Karnataka. Having dedicated her whole life to serving the God Shiva, her White Jasmine Lord, she travelled through the countryside as a female monk. What struck me in her story is that she broke with many cultural conventions of her time. For instance, she walked around stark naked. She talks about it in her poems.

![Akka Mahadevi worshipping Shiva's 'lingam' [= penis]. Illustration from Hindupedia.](http://www.wijngaards-clackson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/deviyakka.jpg)

Akka Mahadevi worshipping Shiva’s ‘lingam’ [= penis]. Illustration from Hindupedia.

male and female,

blush when a cloth covering their genitals comes loose . . .

When the Lord of all life

lives submerged in the world

without showing his face,

how can you be modest?

When all the world is the eye of the lord,

onlooking everywhere,

what can you cover and conceal?”

“You can be robbed

of money in your hand;

can you be robbed

of the body’s glory?

You can peel away every strip

you wear,

but can you peel

the Nothing, the Nakedness

that covers and veils you?

To the brazenly free girl

wearing the White Jasmine Lord’s

light of morning,

you fool,

where’s the need for sari and jewels?”[iii]

I was thinking about all this when listening in, shortly afterwards, to a sermon preached by one of our deacons. In Hyderabad seminary we used to require deacons to preach on Sundays during their last year of formation before ordination to the priesthood.

The theme of the sermon was: “For freedom Christ freed us. Do not submit any more to the yoke of slavery!” Galatians 5,1 – one of my favourite Pauline verses. The deacon then went on to spin his own interpretation.

“Hindus and Muslims suffer on account of their superstitious customs and practices. Their laws impose a yoke of slavery. But we Christians are free. We too have laws but they are not a yoke of slavery. Our Catholic laws do not oppress, they liberate because they reveal God’s Holy Will for us . . .”

“Typical Christian presumption”, I thought. “Hindus and Muslims too will tell you they are doing God’s Will.”

And I realised that this is how the sexuality-hostile Catholic Octopus tightens its stranglehold: by asserting it is God’s Will, not a yoke of slavery. By what authority can Catholic teachers claim it is God’s Will? It made me even more determined to trace the true source of the Catholic Church’s negative view of sexuality.

Then pointers began to come to the surface.

Why had Paul VI stuck to an absolute ban on contraceptives? He did not dare to change direction, it emerged, because “the teaching traditional since Augustine and restated by Popes Pius XI and XII was ‘the plain teaching of Christ’ who warns against false leaders and ‘calls for sacrifice and self-denial’.[iv]

Traditional since Augustine?!

Was he the creator of the Octopus?

[i] Humanae Vitae §14.

[ii] The New Leader 12 Dec 1972; 21 January 1973.

[iii] Excerpts from Prophets of Veershaivism by Mahatapasvi Shri Kumarswami.

[iv] Leo Pyle (ed.), Pope and Pill, London 1968, passim.

John Wijngaards, My Story – My Thoughts, the challenge

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage