In 1964, six years after my ordination as a Catholic priest, I found myself in Hyderabad, smack in the middle of India. St. John’s College at which I was teaching overlooked lush paddy fields on the one side and arid rocky semi-desert on the other. Both are typical of the Deccan Plateau which was pushed up, 60 million years ago, by the largest volcanic eruptions on earth known to geologists.

But I had not come to India to admire landscapes.

St John’s College served the Catholic dioceses of Andhra Pradesh as their theological seminary. Our job was to train students for the priesthood during their final six years of formation. With more than 200 young men to teach and a shortage of qualified staff, I held many functions: professor of sacred scripture, chief librarian, head of the English academy, editor of the college magazine Nênê Velugu, director of summer training projects and spiritual guide to many students. One of them was a youth from Kerala whom I will call Samuel.

I still see Samuel sprawling awkwardly in an armchair facing me. Tall, light-tanned complexion, 18 years old, nervously wiping his shining black hair aside as he threw anxious glances at me.

“Tell me”, I said.

“I’m getting white stuff from . . . well, my front . . .”, he said, pointing at a spot between his thighs. He waited, still looking at me. “From my penis.”

“So?”

“It’s like curdled milk . . .”

He waited again, then spurted out: “I told my neighbour (the student living in the room next to him). He says I’ve committed a mortal sin. Against chastity.”

For a moment I was stunned. Where should I start?

Samuel wasn’t the only one to reveal abysmal ignorance about sex and utter confusion about sexual morality. Other students harboured similar problems and, strangely enough, all those students hailed from the Indian State of Kerala. Our local Telugu-speaking students from Andhra Pradesh were much better informed in matters of sex.

Why was that I wondered?

When visiting villages, Telugu mothers would proudly cradle a baby in their arms. If I showed an interest in the child, a mother might smilingly say: “Magadhu!” – “It’s a boy!”, lifting his nappy to show the baby’s sexual equipment.

Where did that disarming Telugu openness about sex come from?

One reason I discovered is that the Telugus live in close-knit village communities or town neighbourhoods. Tiny mud-wall or brick houses are stacked one against the other. Homes are often one-room establishments in which parents, teenagers and children sleep huddled together, some stretching on low manzams, beds made of ropes strung between a wooden frame, others simply lying on the floor, wrapped in a blanket and resting on a reed mat. Small children are often naked when ambling around the house. As they grow up, they see the adults undress before taking a bath. They notice them make love in the morning, or at night. The monthly periods of girls and grown up women are keenly followed by the whole family.

Moreover our Catholic communities in Andhra Pradesh are firmly embedded within an overwhelmingly Hindu culture. And the main idol worshipped in Hindu shrines and temples throughout Andhra Pradesh is a short or tall shining, black-granite pillar of stone, the lingam. It represents the erect male member of the God Shiva. An elongated saucer-type ring made of stone at its base stands for the yoni, the female sexual organ. The yoni will have a spout on one side so that libations that are poured out over the lingam, collect in the yoni and can easily be drained off.

People in Andhra Pradesh refer to sex with few inhibitions. In English, words like ‘penis’ and ‘cunt’ are considered obscene, but the Telugus freely speak of a man’s lingam and a woman’s yoni. Family names include the word ‘penis’: like Mahalingam, ‘large penis’, and Gurulingam, ‘the teacher’s penis’. There are villages called Lingampalli, Rasalingam, Lingamguntla, Lingamkonda and so on.

Things are quite different in Kerala as I was soon to find out. Meanwhile I bought a 208-page complete guide on sex called Marriage Technique by two Indian doctors and lent it to Samuel as well as to other students from Kerala who needed it. The booklet provided detailed information on all aspects of human sexuality, with sketches and diagrams. The dedication on the front page read: A perfect pilot for your frail little bark to save it from being shipwrecked in the whirlwinds and whirlpools of unenlightened sexuality. Prophetic words indeed!

Spotlight on a Catholic paradise

The State of Kerala adorns the south-west coast of India with a green carpet of fertile lowlands and flourishing hills and mountains. It boasts the highest literacy rate in India. Christians form one fifth of the population, whereas the overall Christian percentage of the country is only 2.3 %. And most Christians in Kerala are Catholic, of one kind or another.

Fishermen along the coast and coconut workers belong to the Latin rite. They were converted by the Portuguese. The Syro-Malankara rite is a branch of Jacobites who in 1930 were reconciled to the Catholic Church. The Syro-Malabar Catholic Church derives from converts of Christian missionaries that evangelized India during the first three centuries after Christ. All these Catholic communities have precious old traditions while also taking part in making our world church come of age during the 20th century.

I began to understand Kerala much better when I explored it thoroughly some time later. You must know that I utilised the six-weeks’ breaks at college during the hot season to methodically visit the homes of my students. I did this on alternative years for Andhra Pradesh and for Kerala. With the help of the students I would draw up a complex travel plan. I would journey to a particular village on one day, then stay with the student’s family for a full day, spending two nights in the village. Then I would spend another day travelling by bus or bullock cart to the next town or village. There too I would stay for a full day. In each place I would get to know the particular student’s home: his parents and siblings, the local church, the school, the family source of income. It was tiring, I tell you, but also revealing. It was great fun because my students and their families were always happy to welcome me.

In this way I exhaustively visited hundreds of villages in remote places tourists will never see. I prayed with people, ate with them, slept in their homes, joined in feasts and funerals, walked with them under the scorching tropical sun and, occasionally, swam with them in a cool refreshing river. I shared their hopes and fears, and began to understand the Indian way of looking at things, the local perspective, the point of view from which they would judge persons and situations. And, I can honestly say, I came to love them: the people of Andhra Pradesh no less than the people in Kerala.

Typical family in Munna Distric Kerala

Allow me, for the purpose of this chapter, to focus on the fascinating Syro-Malabar Catholics living on the slopes of hills and mountains. And I will pick up the story again about Samuel – remember? my student who was ignorant about sex? I will sketch his family whom I visited at the time, adapting circumstances and using fictitious names as I will do throughout this chapter.

Thomas Kurukkalil, Samuel’s father, owns a tea estate. He is a tall, soft-spoken man with kind eyes. He does not say much but commands the total respect of his family. Samuel’s mother Abrianna, a BA graduate like her husband, of light complexion and long black hair which she ties up in a knot on top of her head, is very happy to meet me. Samuel’s 16-year old brother Roshan and 14-years old sister Sona are also intrigued. Both of them study in a local high school and will attend college later. All have a reasonable command of English except for the live-in maid Prafulla who only speaks Malayalam.

The Kurukkalil homestead lies not far from picturesque Munnar in the mountain range known as the Western Ghats. Sitting on the verandah, chatting with the family, I look out on a bush-covered valley stretching away. I can see other houses in the distance, the nearest one a fifteen minutes’ walk down the road. Homes are isolated in this area.

The Kurukkalil home has seven rooms: a spacious lounge, a kitchen, a bathroom and a large bedroom for the parents and smaller ones for the children or guests. Before the meal the family says their evening prayers. A candle is lit before the statue of Our Lady. We are all on our knees. The full rosary of 150 Hail Marys is recited in Malayalam, with Thomas intoning the Our Fathers before each decade. It is followed by the litany of Our Lady and a long list of special intentions to be prayed for.

At the crack of dawn, next morning, the family rises. While Thomas goes off to the workroom at his tea plantation, Abrianna with the teenagers and myself walk to church. It takes half an hour along winding paths that cut through fields and orchards. Other families join us on the way. When we arrive in the parish church, lauds is just beginning. At this time, in the 1960’s, the recital is still done in the liturgical language Syriac. After twenty minutes Mass follows. It is sung, again in Syriac. In spite of it being an early weekday morning, the church is packed.

Samuel belongs to an exemplary Catholic family. So why his ignorance about sex? The isolation of the home may play a part but the main culprit is the intense, devotional Catholic ethos which, obviously, blocks an open recognition of sex. The parents are afraid of the topic. It is being repressed. Samuel is paradoxically the victim of his ‘devout’ Catholic upbringing. And repression breeds revolt and excess. It lies at the root of many cases I come across.

Sister Lily is novice mistress in a formation house. She hails from a Catholic family like Samuel’s. She confides to me, during a train journey to Trivandrum, that she has returned from a Catholic charismatic conference in Cochin. What is more, during an important prayer session, she tells me “a holy priest has exorcised me.”

“Why?” I ask.

“When I was twelve years old”, she says, “my younger brother had a friend staying with us for some months. That boy, who was just one year older than me, used to enter my room at night and creep into bed with me. We were both naked. We used to fondle each other and, at times, make love. I didn’t really know what was going on. Later I understood that it had been very bad. When I confessed it to a priest, he told me I had sunk deep into mortal sin. It’s one reason why I became a religious sister. To make up for it.”

“Why the exorcism?” I ask again.

“At times I wake up at night. I see a black demon hopping about and sitting on my chest. When I switch on the light, he has gone. But I know I’m not fully healed. The devil still has a hold on me. I feel his claws because I have meddled in sex. I was hoping that the holy priest – she mentioned his name – would drive him out for good.”

“Did it work?”

“I hope so”, she replies with a sigh.

Another religious, Sister Aranga, shares her own story when I question her about sex education in Catholic Kerala.

“People mean well, but it’s bad”, she says.

“Last year I took part in a renewal seminar for religious in higher education. Both men and women attended. I met a young priest lecturing in Aleppey and we had some very interesting conversations. He told me that, though he was 35 years old, he had never properly seen the body of a woman.”

“So?”, I said. “How did you respond?”

“Well”, she smiled at me. “This may shock you but I too had never seen the body of a man. In sculptures, yes, but not alive. So we arranged to meet in his room when nobody was about – during one of the conference sessions. Both of us undressed. We took time to examine each other’s bodies. We did not touch each other, of course. Just looked.”

“Wonderful!”, I said.

“I’m glad you think so. We both felt we needed to do this. To grow up and be mature.”

I witnessed a more depressing outcome of keeping sex in the dark by what Theyya told me a few days before she was getting married. Her mother had died early. Her father had been a strict man, but he often left his children at home.

“My brother Kurian and I often felt lonely”, she said. “Our aunt was there, but she would always go to bed early. Kurian and I comforted each other by sleeping together night after night. We made love not really knowing what we were doing. It’s a wonder I never got pregnant.”

“Anyway, you are getting married”, I said.

“That’s the problem. My father has arranged it. I don’t love the man he has found for me. I will always love Kurian. I will have to go ahead with the wedding, but it won’t work. Kurian will remain my real husband . . .”

An older woman, Akka, told me with a chuckle: “In those Christian homes parents don’t realize what happens to your young daughters.”

“Like what?”

“Well, when I was six years old, my uncle who was just a young man at the time, would pick me up and fondle me. He would then put me on his lap. Since I wore nothing under my skirt, he would push it aside and rub my naked bottom over his genitals. Nobody else noticed.”

Such examples, all true, will be enough to make the point. And I assure you that I did not seek out such information. I just came across it. And I connected it to the alarming ignorance about sex displayed by some theological students from Kerala.

The Catholic obsession

Anyone who knows the Catholic Church will have recognised that what I have been narrating regarding the Catholic community in Kerala applies equally to traditional Catholic communities anywhere in the world. Fear of sex and the attempt to repress it are, regretfully, international Catholic phenomena. Catholics in Kerala are not more beset by the sexual muddle than Catholics elsewhere. The problem does not lie in a country or its culture, but in traditional Catholicism.

I knew it only too well from my own country: Holland. In the twentieth century the Dutch Catholic Church was reasserting itself after centuries of Protestant persecution. The Dutch Catholicism I grew up in was fiercely loyal and totally committed to their faith. At the time 14,000 Catholic missionaries from the Netherlands evangelized Asia, Africa and Latin America – the largest national group of Catholic missionaries in the world, matched only, at one point, by the Irish. Dutch Catholics were thorough. They meant business. Unfortunately this also applied to sexual morality.

Let us stay at home and take a look at my family.

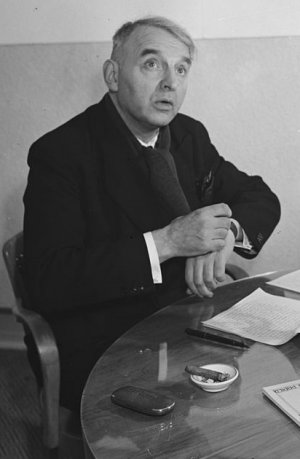

Father “Henri De Greeve” photographed by Koos Raucamp (ANEFO) in 1946 before a radio talk.

As I have narrated in an earlier chapter, my mother came from a family of nine children. None of these children received any sex education. They were warned, again and again, that indulging in sex was sinful – a mortal sin! – but sex itself was not explained. Sex was haunted by fear and hid in darkness. My mother once told me that as the oldest child in the family she accompanied her mother, my grandmother, to a conference in the parish church. Preacher was renowned Father Henry de Greeve.

“He preached for an hour”, my mother said. “Thumping his fist on the pulpit he roared: ‘The world wants sex, dirty sex. But I warn you: sex will drag you to hell! Everlasting hell!’ ”

“It was awful”, my mother recollected. “Awful. Then he shouted: ‘I tell you parents: to save your children from hell, keep them green! Yes, keep them green!’ ”

But keeping children ignorant is a recipe for disaster.

One of my aunts, Caroline, two years younger than my mother, only found out during her wedding night what intercourse means.

“It was a drama”, my mother said. “Caroline was shocked. Sickened. Disgusted. She cried the whole night. The marriage was scarred for the rest of her life.”

Two other aunts were incapable of opening and maintaining a normal relationship with potential partners. They were doomed to remain spinsters for life. Three of my uncles fled into religious life, joining a congregation of teaching brothers – with varying degrees of success.

“I was lucky”, my mother said. “When I got engaged to my father, he discovered my anxiety and ignorance about sex. He gave me booklets to read that explained everything. I had to read them in secret because my father would have taken them from me.”

My grandfather, in fact, in spite of fathering so much offspring himself, firmly adhered to the traditional Catholic policy of sexual repression. One day he cycled with some of his children along the Apeldoorn Canal. It was summer. Some half-naked men were swimming in the water. As soon as he saw this, my grandfather shouted down the line: “Look left! Look left!” – that is: away from the canal. Nudity was absolutely tabu.

On Saturday evenings all the children would be given fresh underwear. Of course, with such a large family, girls crammed into one bedroom, boys in another, changing your vest could reveal breasts and changing nickers even more unspeakable body parts. So grampa arranged a strip-and-cover ritual. He would wait till all of them were standing near their pile of change. Then he would blow a whistle and turn off the main light switch in the house. In total darkness vests and nickers were taken off, fresh ones put on. Sin averted! Imagine the spiritual damage that could have been done if anyone saw his or her own body, or that of a sibling!!

Fear of the naked body also reigned supreme in convents. One nun confided to me that sisters were ordered to wear a designated ‘chemise’, a kind of night shirt, when taking a bath. They were allowed to wash their nipples and genital area under the chemise, but on no account were they allowed to look at it.

When I stayed in hospital for eye treatment which involved a fever cure, another nun narrated how she had been visited by her superior.

“Sister”, the superior had said. “I pity nurses like you.”

“Why?” she had asked.

“Well, nurses like you have to wash other people’s bodies. You are seeing so much sin every day . . .” She meant seeing the naked genitals of women and men!

Murderer with many arms

Such things were still in my mind when I was invited to take a short trip on a fishing boat off Kovalam Beach in Kerala. The sea was calm. I admired the rugged fishermen as they sought out and located a net left overnight across a tidal underwater flow one mile from the shore.

When the net was pulled up from the water it revealed a mass of glistening wriggling sea creatures: sardines, carps, lemmings, lobsters, crabs and – to my delight – an octopus.

An octopus lives on the bottom of the sea. Having no bones, it can flatten itself and squeeze through narrow slits. It is a master of camouflage and disguise. It can change the colour of its skin at will, turning speckled and light yellow on light yellow sand, grey when slithering on grey rocks, green when hiding among weeds. But all the time its eight arms are ready to strike out and strangle unsuspecting victims. The octopus lies in hiding, unseen, till it kills with deadly ferocity.

This stealthy strangler, I saw, was the perfect image for the insidious Catholic obsession with sex and hostility to sex. Hiding under clever guises of pious camouflage, the octopus of sexual repression wreaked havoc with its many strangling arms. It held teenagers in a state of terror of its unseen threat. It snuffed out the joy of sex in the bedrooms of Catholic couples. It doomed timid Catholics to avoid marriage altogether and drove more adventurous Catholics, by rebound, to explore incest, pornography and other sexual excesses.

But where did this unchristian sex-demolisher come from? And how had it managed to infest the soul of traditional Catholicism?

John Wijngaards, My Story – My Thoughts, spotting the Octopus

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage