Faith formation through video

Before I proceed further in the story, I need to explain that the purpose of our Centre was to promote adult faith formation. Many people do not grasp what this means or why it was, and still is, of such importance to the Catholic community.

After the Second World War enormous changes affected the western world. Previously mass attendance had been good in Catholic communities. Now it slumped to less than 30% in most countries. Teenagers and young Catholic couples drifted away from the Church. I have written about this on a number of occasions. See especially my 1982 report to the Mill Hill Chapter, section three (http://www.johnwijngaards.com/society-home-regions/ ), and my position paper ‘God and our new Selves’ to a Consultation in Vienna convoked by the Council of the European Bishops Conferences in 1998. http://www.johnwijngaards.com/god-new-selves/.

The causes of church decline were numerous: in people’s eyes science was winning the battle over religion; society had become mixed, pluriform and fragmented; people were asserting their own autonomy over against traditional morality; they were becoming ‘fulfilment seekers’ rather than obedient followers. Meanwhile the official Church refused to update its views on family planning, women’s equality, lay participation in church governance. At the root of it all was the fact that educated Catholics discovered their own responsibility as ‘adults’ while the ecclesiastical institution still treated them as ‘infants’. This eroded faith.

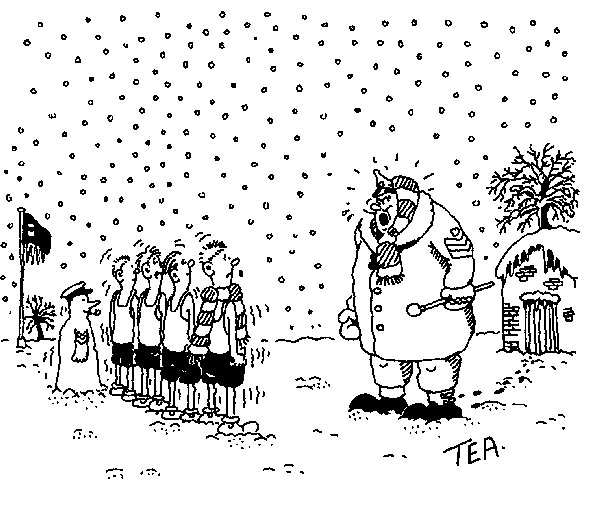

“Don’t shiver! When I tell you it is warm, it IS warm!” From ‘How to Make Sense of God’.

Most Catholics were instructed in doctrine through a catechism which was imposed on them in the primary and secondary schools. Texts had to be learned by heart, rather than key beliefs discussed and explored. At Sunday Mass, the priest would preach a homily which consisted of often repeated and predictable assertions. There was no room for questioning, for debate, for coming to accept a point of faith after mature reflection. But faith can become only one’s own conviction after much thought and a personal ‘adult’ decision. In other words: most teenagers and Catholic adults were supported in faith only by an immature and infant indoctrination.

Our aim was to provide tools by which priests, teachers and other religious educators could help highschool students and adults rediscover their faith and make it a personal conquest.

Our principles for deepening people’s faith were as follows:

- Give information. Don’t preach.

- Respect people’s doubts, search, individual pace.

- Realise the importance of people’s own experiences.

- Encourage people to think for themselves, to take their own decisions when they are ready for them.

- Make our material through international co-production, and offer it in forms that can easily be adapted to other cultures and pastoral circumstances.

I realised that deepening one’s faith is best achieved in a group. Reflection and discussion in a community setting greatly enhance the effectiveness of learning. The sharing of experiences and the stimulation by others make participative group learning the ideal ambient for personal growth.

Why we chose video courses

One of the stated purposes of our Housetop Centre was to produce tools for religious education that could be used both in our European home countries and our third world mission territories.

I wondered at the time, I am talking about the 1980’s, what would be the prefect tool for adult faith formation. My team member in Housetop Jackie Clackson and I studied various options available. We realised that good methodology would need to combine the input of new information, an element of ‘parable’ to stimulate participants’ imagination and a process of discussion and reflection.

Jackie was an artist with a batchelor’s degree in Art & Design. In the months leading up to our opening Housetop she had studied the use of creative media for catechetics in Lyons, France, and Toronto, Canada. Slides were the favoured medium at the time and Jackie was a skilled photographer. So we started looking at the potential of slides as the ‘parable’ element. In fact, for one of two years we used to organise ‘prayer sessions’ in our basement chapel, sessions which consisted of an opening prayer; a display of a series of slides developed by Jackie; reflection in silence; discussion and opening prayer. Jackie’s slide series were very beautiful. They ranged from showing the sun rising over the horizon and throwing ripples of light across the sea, to delicate close-ups of flowers, insects, mushrooms in a spring forest; or to faces of agitated men and women in crowded street scenes. While Jackie projected her slides, she would play matching music in the background.

The prayer sessions were a success. They attracted a wide range of keen participants. But the element of focusing on elements of Christian doctrine was missing. Also for maximum effect the slides often needed an inspiring introduction. Moreover, change was in the air. Video was rapidly replacing slides. Because of its presenting moving images, it was far better suited to tell a story. And video was gaining ground everywhere.

In 1989 experts at an international meeting in Rio de Janeiro described it as `a wildfire, expanding uncontrollably in all directions, defying economic assumptions and crossing all cultural barriers.’ They were not discussing AIDS, terrorism, unemployment or some other global menace. They were trying to understand video. Reporting on the video revolution all over the world, Time Magazine stated in September 1989: “From the highest peaks to the deepest jungles, the eyes of the world are glued to the wondrous and irrepressible offerings of the VCR (the video cassette recorder).” There was hardly a place on earth where video was not making inroads, it reported. In some countries, video was people’s answer to heavily censured state television. In other countries, video could bring programmes to areas not covered by TV networks. Often video became the poor man’s cinema, presented in video parlours that spread to slums and villages.

At the time many people thought that the use of video in the pastoral ministry was no more than a gimmick, a giving in to the latest fad. But we came to another conclusion. Video proved, in fact, an entirely new medium ideally suited to support pastoral programmes. Video could help pastors and religious educators communicate more effectively in an audio-visual culture. Let me explain.

Video as a new medium

Many looked on video as an extension of TV. Sometimes it is. When we use video for time-shifting: for recording a programme we want to watch at a more convenient time. But video proper, as a catalytic tool, is entirely different from TV or radio.

A mass medium, such as radio or television, addresses individuals in a crowd; is beyond the control of the individual; generally does not elicit or encourage feedback; often results in a process of one-way, top-to-bottom entertainment-oriented manipulation. Some analysts maintained that the greatest danger of TV lies in its destroying real human communication by preventing reciprocity, feedback, argument, altercation and critical response. Harvey Cox said that as Christians we should expose the fraudulence of such anti-communication. We should alert the victims of this non-dialogical propaganda and sponsor media that foster dialogue, response and commitment.

Enter the group media. A group medium, such as video, functions as an input, a catalyst, within a group process. By group I mean a somewhat homogeneous, relatively small number of people who can actively engage in an exchange of insights and feelings. Video, as a group medium, presents life experiences with the sole purpose of making people enter into the issue emotionally and thus initiating reflection and discussion. The self activity of the viewers after the viewing is more important than the viewing itself.

Video, as a group medium, could mobilise men and women, single or in groups, for change, for accepting new insights, for adopting new attitudes, for risking conversion and renewal. Video, therefore, if well employed, was ideally suited to help the process of adult catechesis, of youth formation and of parish renewal, all of which are best achieved within groups. It is in such groups much more than in large assemblies that people find they belong. Here they more naturally receive support from others as from a real ecclesia, a community of believers. Avery Dulles, the well-known ecclesiologist had stated: “People find the meaning of their lives not in terms of institutions, however sacred and awesome, but in terms of the informal, the personal, the communal. They long for a community which, in the midst of all the conflicts of modern society, can open up loving person-to-person communication.”

Whereas TV silences and dominates, and can destroy real communication, video is a tool that stimulates and builds up. It is entirely at the service of the community. We realised that these are qualities we could make to work for faith formation.

Video in our audio-visual culture

In the 1980’s it was becoming abundantly clear that people had begun to live in an audio-visual culture. There were ten times more video rental shops than bookshops in London. People had begun to spend an average of four to five hours a day watching TV. But what did it mean?

Sociologists asserted that the strongest and most erosive power of television did not lie in its occasional flirt with physical violence and sex, but in its all-pervasive presentation of mediocre values. As Gregor Goethals showed in her study, TV Ritual (Boston 1981), TV created the new symbols which, in turn, moulded people’s way of thinking. Human beings need symbols that convey and fix a network of social and personal meanings. The images of television provided the makings of an alternative liturgy that offered its believers a worship of humanist ideals. Our audio-visual culture deeply affected the way people had begun to think.

And this was a true revolution. For in the past had been fed by a literary tradition. It focused on clarity of concepts and definitions. It was characterised by a preoccupation with ideologies, with written texts, with literary style. As pastors and theologians we used to believe the Good News was primarily proclaimed through clear notions and precise words.

Visual thinking on the other hand proved to be more centred on people, on their life experiences. It had a more comprehensive way of approaching realities. It was is more open to emotion, to surprise, to wonder. It worked with images and metaphors. And this had advantages. We felt that as Catholics we should welcome this return to image and metaphor. As theologians we knew that regarding God and things of God, humans can speak no other language than the language of analogy and parable. God expressed himself most fully to us in the pictures of nature, the images of Sacred Scripture and, last but not least, in Jesus Christ, who is the incarnate image of God. “Who sees me sees the Father” (John 14,9). God relates to us in sacramental signs; in a liturgy that speaks to eye and ear as well as to the mind; in a whole network of sacred symbols.

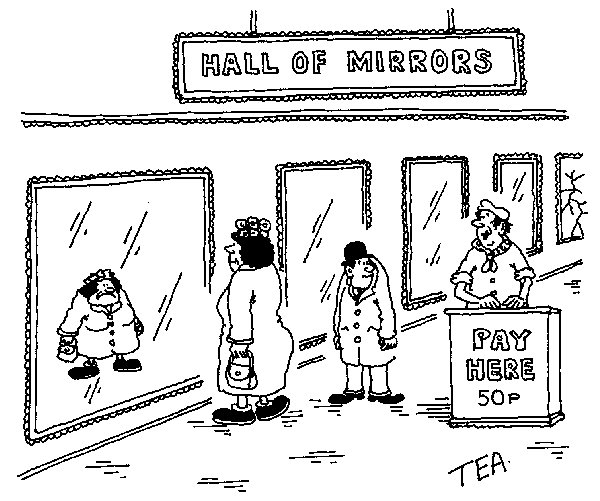

Stories are mirrors that can teach us about ourselves. From ‘How to Make Sense of God’.

As a Church we have always been theatrical. We expressed faith through mystery plays. We portrayed the history of salvation on our stained glass windows. We love beautiful liturgies. In all this we have always known that images are not just tools, `visual aids’, gimmicks. We have known in our bones that through sacraments, signs and icons we were somehow touching God and the divine.

As the pundits put it, through the audio-visual exposure viewers could enter into the life experience of faith with all their emotions and the associations of past memories. That is why the presentation of faith in stories that can be seen on the screen agreed with our long-standing `Catholic’ tradition. A good Christian video could become a parable and the more it was seen in successive sessions, the more it could assume the function of a parable.

Appreciating this positive potential of religious videos, we decided it had to respect its special nature. An audio-visual experience cannot be substituted for by notional assertions. Rather, meeting life in images naturally leads to a sharing of one’s own deep feelings and convictions. This in turn calls for a critical examination of one’s own attitudes and thus opens the door for change.

The advantages of video

Another reason why we decided to adopt video as the main tool in our faith formation programme, was its practicability. Group media had been with us for some time in the form of displays, photographs, slides, and so on, but these were limited and, at times, awkward to use. Video was very easy to handle. We could offer the visual element on one cassette.

In the 1980’s video recorders were found almost everywhere. In the UK, market penetration of homes was well over sixty per cent. In many countries there were communal VCRs. Then again, if a video recorder was not available, it could easily be taken along and set up for a presentation.

Video, we knew, can give an input we could never match even with the most consummate eloquence. To make it yield its full potential, however, faith formators must allow it to speak. This means following the nature of video.

We resolved to design our video programmes for use in more than one full discussion session. Using a video just once, in a one-time viewing, should be avoided. Rather after perhaps seeing it once all through in an initial session, it should be viewed again, section by section, in subsequent sessions. There were good reasons for this. Since a proper video course is made to initiate discussion, the text and images are too concentrated for absorption at once. After all, the discussion afterwards, that is: the process of change, is more important than the viewing. And the parable function increases with increased viewing and reflection.

We reflected on the fact not only that Jesus taught in parables but that “he never spoke to the crowds without parables” (Matthew 13,34). Amazing! He never spoke without parables. So we asked ourselves: does video make it possible for us, teachers, shepherds, spiritual guides and lay leaders, to follow his example in our day and age?

How our video courses worked

So we decided to fully explore the potential of video.

Most of the new Christian videos that appeared at the time were homilies, priests preaching at people. That was the last thing we wanted. Again it reduced listeners to the level of infants. We concluded that a totally new format was called for, a format that I will now describe.

The video courses we designed were composed of a course book, a video and a guide book for the leader of the group. A full course contained nine sessions. Parish groups following a course would complete these over nine consecutive weeks. In high schools, religious education teachers might arrange for two sessions a week.

Imparting new information. Though all members of the group were supposed to possess the course book and prepare for the session by reading the relevant chapter at home, we expected someone in the group to present the contents of the chapter viva voce. Just reading text cannot replace the voice of a living `speaker’. A speaker can impart information, explain new notions and relate to actual people much better than printed text ever can.

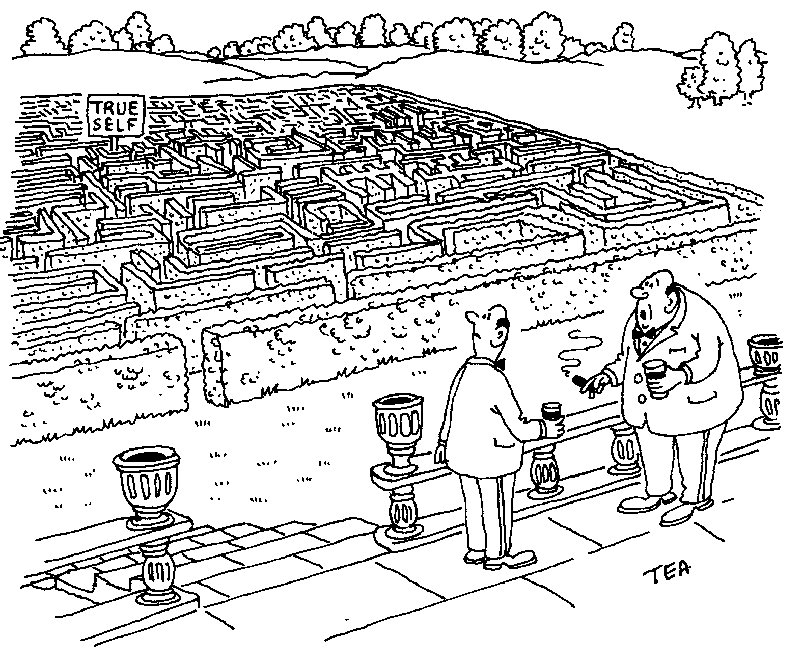

“I asked my priest ‘who am I?’ — ‘Seek and you shall find’, he replied.” From ‘How to Make Sense of God’.

We recommended that those members of the group who had the charism of being able to provide the instructional input, should be drawn in to fulfil this ministry. One did not need to have theological or religious training for this. Our experience showed that very ‘ordinary’ people could present the material in an excellent way.

In practice this meant that the leader assigned portions of the course book to one or more `speakers’ in advance (usually the week before), asking them to present the contents to the group. Obviously, other members of the group were also expected also prepare themselves by reading the relevant chapters of the course book during the week running up to the session. In spite of that we stressed that the instructional portion of each session should be presented viva voce even if all the members of the group had a copy of the course book and had read the text themselves.

Providing the element of ‘parable’. The main function of the video was to confront the group with actual life. The story on the video fulfilled this role. Even though here too logical arguments were presented, they had now been set in the context of a story, of actual life. We believed that only visual narration could portray life as it is, with all its traumas, worries, emotions. Our search for God is ultimately not just an intellectual exercise. It involves us as complete persons.

Our videos presented stories. However, they were not an ordinary story. They had been scripted to be seen more than once. We warned participants that, because of the entertainment character of most TV programmes, they might have become used to writing off a programme once they had seen it. Our kind of story was different. It had been purposely made to achieve its highest benefit during a second and third viewing (and even more), each time seen with more insight and from a new perspective.

For all visual media present images. And our instructional video gave the fullest possible scope to this dimension. We planned and ‘planted’ layers upon layers of images as seeds in the story. Once people became aware of them, their own imagination could take over. For images are open-ended, are parables. They can become vehicles for a person’s own thought in quite unique and unexpected ways. All human thought ultimately rests on image, model, metaphor. Even physics, mathematics, economics and any other form of reasoning employs images. So we realised the full potential of images to fathom and express the deepest realities of life.

Enabling shared reflection. Involvement by all members of the group in reflection and discussion was crucial for the success of the learning process. We aimed at changing the perception and commitment of the individuals, and of the group as a whole. For this to succeed people’s personal experience had to become a vital ingredient in the process of faith formation. Discussion could help to draw this out.

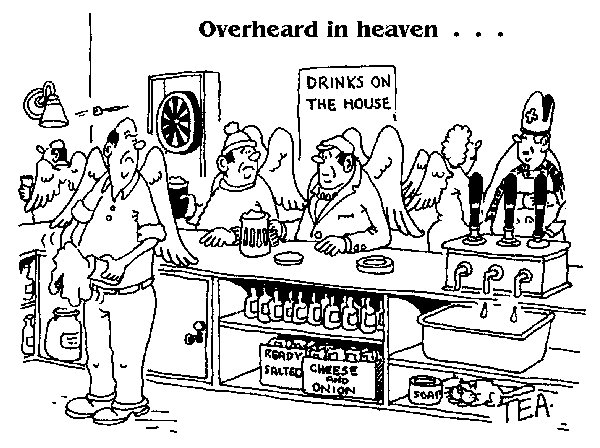

“In our parish we could discuss everything freely – even criticise the Church”. From ‘How to Make Sense of God’.

We suggested that, as a general rule, room should as much as possible be left for the group to react spontaneously to the new information and the ‘parable’. We hoped that when the teaching had been presented and the related video story seen, the group would spontaneously respond. But if a search did not arise naturally from within the group, the group leader should introduce questions that might achieve the desired result. He/she could resort to various strategies depending on the needs of the group. He/she could use relevance questions, telescoping questions or specific questions.

Relevance questions provoke the participants to a direct, personal response. They will be of this nature: What struck you most in the presentation and the story? How does it compare to your own experience? Do you agree or disagree with what has been said?

Another approach, we suggested, could be as follows. In a sequence of telescoping questions, the leader gently steers the group from the general to the particular. Questions could concern:

- clarity of concepts: Did you understand everything?

- recognition of values and truths: In your view, what is at stake here?

- application to one’s own life: How does it affect us?

- openness to change: What shall we do about it?

The group leader could also enliven the discussion by raising some specific questions relating to the topic in hand. In the session outlines printed in the Guide, some such specific questions were suggested. These were a handy ‘reserve’ at the leader’s disposal, in case the discussion were to ‘dry up’. However, this, we predicted, was not a likely course of events.

Initiating a prayer of response. We wanted each group to recognise that it’s response to the issues presented and discussed, would remain inadequate if it missed the element of prayer. And prayer had to be as personal as possible, a response of this community of Christians offering their thoughts and intentions to God who spoke to them through his Word, through the group and through life.

Of course, various forms of prayer could serve this purpose, depending on the nature of the group. The prayer did not need to be long. Songs, readings from Scripture, reciting a Psalm, and so on, could be valuable parts of the common prayer. But it would be inadequate, we suggested, to limit the group’s prayer to texts from books. Meaningful elements for the prayer should be taken from the group’s own reflection during the session. Moreover, both moments of silent prayer shared by the group and spontaneous prayers by individual group members would be powerful elements of a group’s response in prayer.

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage