Dealings with the Vatican

So far I have spoken about the events surrounding my declaring in public that I was going to resign from exercising my priestly ministry. But, of course, long before that happened I had been working at sorting out my official position with Rome. I wanted to avoid simply disappearing from the Church scene as other priests had done, mainly to get married. Since I had been officially in the service of the Roman Catholic Church, I wanted my new position officially sanctioned and recognised. Only in that way I could efficiently continue my prophetic mission in the Church.

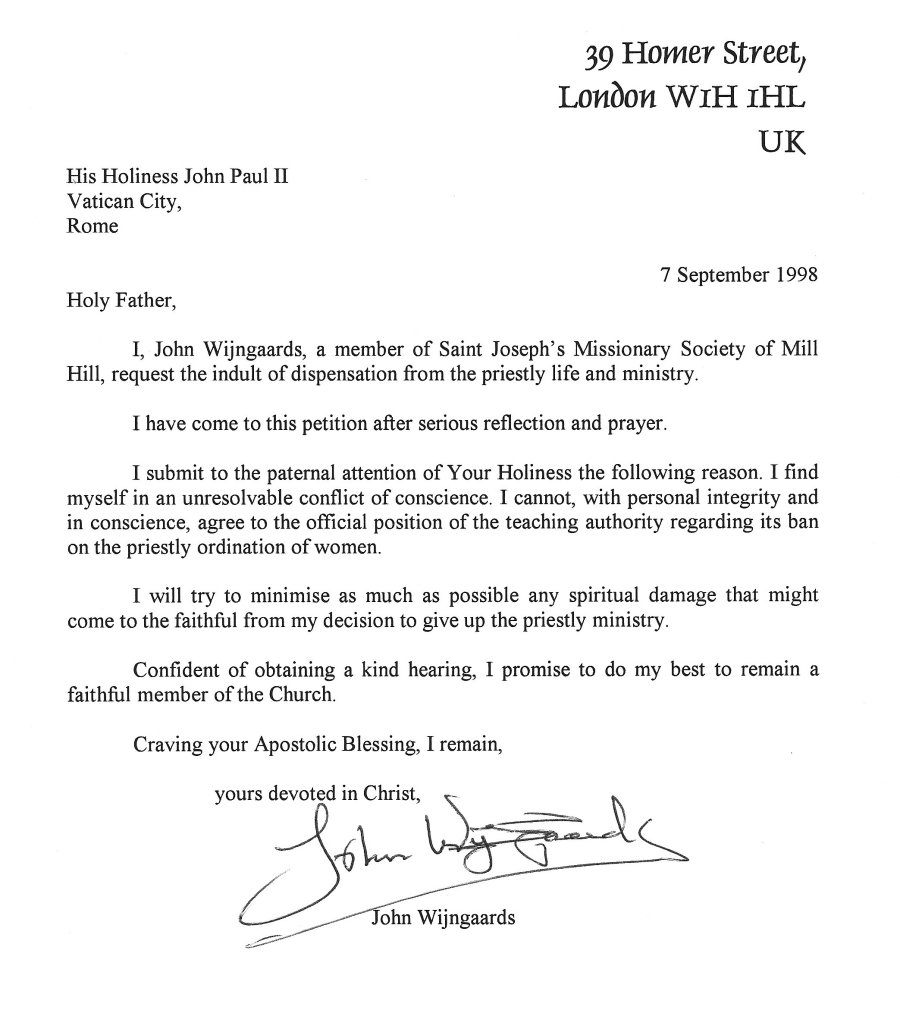

So, after consultation with Father Maurice McGill, Superior General of Mill Hill, I sent the following letter to the Vatican through the services of Father Hans Stampfer who was our Procurator General in Rome.

You will notice that in my letter there is no mention of celibacy. In fact, in a letter to Maurice McGill of the 18th of August 1998 I had explicitly excluded this as the reason for asking dismissal from the ministry. “After long reflection, discernment and prayer, I have come to the conclusion that I have to withdraw from the priestly ministry. Therefore I request you to obtain laicisation for me from the Roman authorities and to grant me an indult to leave Mill Hill Society, in accordance with No C 87 of our Constitution. There is no need for you to apply, on my behalf, for a dispensation regarding celibacy.”

You will notice that in my letter there is no mention of celibacy. In fact, in a letter to Maurice McGill of the 18th of August 1998 I had explicitly excluded this as the reason for asking dismissal from the ministry. “After long reflection, discernment and prayer, I have come to the conclusion that I have to withdraw from the priestly ministry. Therefore I request you to obtain laicisation for me from the Roman authorities and to grant me an indult to leave Mill Hill Society, in accordance with No C 87 of our Constitution. There is no need for you to apply, on my behalf, for a dispensation regarding celibacy.”

A long application procedure followed that would last from September 1998 to April 1999. Hans Stampfer and Father Ludwig Jester, our Mill Hill expert on church law, had various meetings with Dom Piero Amento of the Congregation of the Sacraments. To cut a long story short: the Vatican did not distinguish cases of conscience like mine, they only handled one form of application which centred around the question of celibacy. I was told I would have to follow this procedure.

I decided to follow suit. In my priestly life I had discovered how ill-conceived the imposition of legal celibacy on all priests of the Latin Rite was. Moreover, I had come to the conclusion that acceptance of celibacy in my personal case had also rested on faulty assumptions. When we became sub-deacons, we were automatically assumed to have voluntarily embraced celibacy – it even was glibly called ‘an implicit vow of celibacy’. With hindsight I knew it had been invalid in my case. All this would come out in the subsequent process. I decided to play along.

The procedure of examination

As a person asking to be ‘laicised’, I had become a ‘petitioner’, a term used throughout the process. The key element, it turned out, in Rome’s handling of cases of ‘laicisation’, was a form of ecclesiastical grilling to establish the true situation of the petitioner and his genuine motives. So a long questionnaire with 44 questions was handed to me as petitioner. I had to fill in my responses and swear to them under oath in the presence of two ecclesiastical witnesses. The form was called ‘Interrogation of the Petitioner’.

I must confess that, as I read the questions, a felt deep anger surging up in me. So this is how Rome treated priests struggling with a celibacy that had been laid upon them under false pretences! Instead of at least a partial acknowledgement that they were also victims of the system, they were forced as humble petitioners to falling on their knees and plead for pardon from the almighty church institution! What is more, to get out of their predicament, they were morally compelled to reveal matters of conscience under oath to ecclesiastical judges outside the secrecy of confession! How could a priest in trouble protect himself against such a system? Now Jesus had told us to be ‘simple as doves and cunning as serpents’ . . . But I decided this was not the time to rock the boat. It was time to play the game.

I still have a copy of the answers I provided. I will not bore you by printing out my replies to all questions. They mainly concerned my history and previous ministry, already familiar to you from previous chapters in my account. But I print here a record of the paragraphs that mattered, with my responses.

§ 24. Did you during your time of priestly formation have an adequate appreciation of the reality of living a celibate life? Were there emotional difficulties of any kind? If so how did you cope with these?

“My formation towards a mature attitude to sexual life and celibacy has been highly unsatisfactory.

- I did not receive sexual education from my parents. They were shy and

- Questions I raised with my confessors in the minor seminary regarding chastity

were not seriously answered. - Since I had no sisters and since we were explicitly told by seminary authorities to stay away from girls, I had no normal friendships with people belonging to the opposite sex.

- Also during my major seminary time the topic was avoided. Of course, I knew the ‘facts of life’ by then, but when I talked to my spiritual directors (Frs. Henry

Knuwer and Serafino Masarei) my doubts were dismissed as temporary.”

§ 32. When did you begin to feel dissatisfied about the Priesthood? What was the nature of the dissatisfaction?

I have never felt dissatisfied with the priesthood as such, but I have gone through

a crisis on account of the ecclesiastical obligation of celibacy. As I have explained above (see no 24), I had not been adequately prepared for celibacy during my seminary training. This caused a lot of turmoil in me during the first decades of my priestly life. I went through a personal search.

During a retreat in 1975 I came to the clear recognition, in consultation with my

spiritual director Fr. Finbar Connolly CSSR, a Moral Theology professor in

Bangalore. that a vow of celibacy in my case had been personally invalid.

The reasons were:

- I had entered celibacy with substantial errors in my mind regarding the substance of the vow. Full and complete knowledge of the object of the vow was missing. I lacked proper sexual education. I was deprived of the experience of women. I did not understand marriage.

- I had also been misled by the motive (causa final is) of the vow since I had been under the mistaken impression that the priesthood and marriage could not go together.

However, I decided not to act on this realisation because of my sense of duty to

the people who had been entrusted to me, since I was a priest.

Throughout my ministry I have, in relating to women, not allowed any friendship

to become incompatible with my sharing in the priesthood of Christ. Regarding

chastity and sexual ethics, I have, as a rule, acted in accordance with my conscience.”

§ 35. When did you decide that you would no longer continue as a priest? What were the circumstances that led up to this decision? What were the reasons behind it?

* “The first doubt and initial conflict of conscience that arose in my mind was

occasioned by Pope Paul VI’s encyclical Humanae Vitae, because it banned the

use of contraceptives in marriage. I was in India at the time. As a theologian I strongly disagreed with the reasons given in the encyclical for the decision. I also deplored the spiritual and moral hardships thus inflicted on the faithful.”

* “I have also been distressed by the Holy Father’s insistence on obligatory celibacy for priests in the Latin Rite. I have seen many valuable companions and precious students I had formed in the seminary, being lost to the ministry on account of this practice.”

* “When the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith published its reasons for

rejecting women from the priesthood in 1976, I published counter arguments in

my book Did Christ Rule Out Women Priests? As a theologian I continued

researching this topic, becoming more and more convinced that there are no valid arguments from Scripture or Tradition that women can legitimately and validly be ordained priests. I also became involved in the pastoral ministry of guiding women who are seeking their rightful place in the Church.”

“I decided to give up the priestly ministry on account of the ‘Motu Proprio’ of John Paul II Ad Tuendam Fidem (28 May 1998) and the accompanying letter by

Cardinal Ratzinger (29 June 1998). Since these documents prescribe adhering to

the belief that women cannot be ordained priests on pain of no longer being in

communion with the Church, I felt in conscience obliged to offer my resignation

from the priestly ministry.”

“After long prayer, reflection and consultation, I explained my situation to my

Superior General, Fr. Maurice McGill towards the end of August 1998, when I

applied for laicisation.”

§ 39. What are your motivations for requesting this dispensation?

“The reason that moves me to give up the priestly life and apply for a dispensation are the following:

- As a theologian I owe it to my own integrity and truth to hold my belief that women can be ordained priests. After long and serious study I am convinced that the ban on women’s ordination is not legitimately founded on Sacred Scripture or Tradition, has not been arrived at after proper consultation in the Church, and is harmful to ecumenism and the spiritual wellbeing of the faithful.

- I see at the same time that the official Church, whose ultimate pastoral leadership and teaching authority I have to respect, obliges all Catholics to accept its own view.

This has put me into an intolerable conflict of conscience. I can no longer represent the official Church while disagreeing with it on such a fundamental

matter.”

§ 40. In the final analysis, why do you find yourself unable to persevere in the Priesthood?

“Once a priest, always a priest. I do not intend to give up the priesthood in as far as I will continue, to the best of my abilities, to preach the Good News of Jesus Christ. What I find it impossible to continue, in the present climate of the Church, is to exercise my priestly ministry.

I feel that as long as there is this conflict between the convictions I sincerely hold in my heart and mind as a Catholic and theologian on the one hand, and the

official teaching authority of the Church on the other, I cannot resume my priestly work.”

§ 41. Have you attempted civil marriage? If so, what is the name of this woman? Is she free to marry?

“I have not attempted civil marriage.”

§ 42. Do you have children?

“I do not have children.”

I submitted my replies under oath in the presence of two witness: Fathers Bill Tollan and Fons Eppink, both members of Mill Hill’s General Council.

Response from Rome

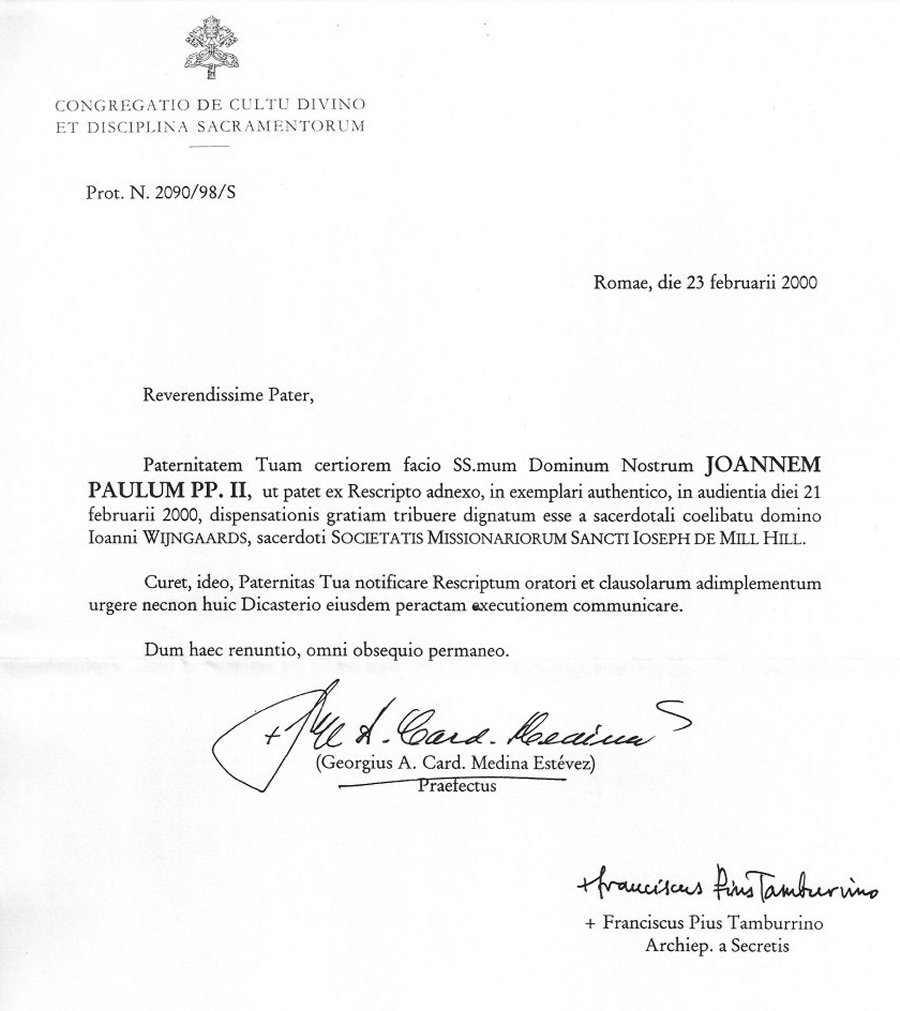

In total it took 18 months before the Vatican finally communicated its decision. A letter dated 23 February 2000 conveyed the message that Pope John Paul II had graciously granted me dispensation from my priestly celibacy. But I would have to observe the injunctions laid down in an accompanying edict called a ‘rescript’ in Vatican parlance. I print a copy of the official Roman document written in Latin:

The accompanying two-page rescript was also in Latin. Its text is very revealing of the official Church’s attitude to its priests. I will print it here in my own translation. Remember I am quite an expert in church Latin. During my studies in Rome most of our lectures and all examinations, written or oral, were in Latin.

The accompanying two-page rescript was also in Latin. Its text is very revealing of the official Church’s attitude to its priests. I will print it here in my own translation. Remember I am quite an expert in church Latin. During my studies in Rome most of our lectures and all examinations, written or oral, were in Latin.

“Congregation of Divine Worship and Discipline of the Sacraments, Protocol No: 2090/98/S

Father John Wijngaards, priest of St Joseph’s Missionary Society of Mill Hill requests dispensation from priestly celibacy and all obligations connected to sacred ordination.

Our Most Holy Lord Pope John Paul II, on the 21st of February 2000, after having taken note of the case through the Congregation of Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, has acceded to this request, subject to the following regulations:

- The dispensation comes into force from the moment of its concession;

- The written confirmation of this dispensation should be notified to the petitioner by the competent ecclesiastical superior and this should, inseparably, include both dispensation from clerical celibacy and the loss of the clerical state. Never will it be allowed to the petitioner to separate these two elements, namely accepting the first and refusing the second. If the petitioner belongs to a religious order, this rescript also concedes dispensation from the vows. The same, moreover, brings with it absolution from church sanctions, to the extent this might be required.

- A note about the concession of this dispensation should be entered into the baptismal register of the petitioner.

- With regard to the celebration of a legal marriage, the norms should be applied which are prescribed in the book of church law. The local bishop, however, should see to it that the celebration is performed cautiously, without pomp and public display.

- The church authority whose task it is to notify the petitioner of the rescript should urgently exhort him to take part in the life of God’s People, in the manner that is congruent with his new state of life. He (the former priest) should edify people and show himself to be an honest son of the Church. At the same time he should be informed of the following regulations:

- The priest who received the dispensation by that fact itself loses all rights attached to the clerical state, all dignities and church offices; he is no longer bound by other obligations bound to the clerical state;

- He remains excluded from exercising the sacred ministry, except in matters referred to in Canons 976, 986 § 2, and therefore he may not preach the homily in church. Moreover, he may not function as an extraordinary minister of distributing holy communion, neither may he exercise a leadership role in the pastoral field;

- Also, he may not fulfil any task in Seminaries or similar Institutes. Neither can he carry a leadership role or teaching function in other educational institutions which are somehow under control of church authority, (especially) in such institutions he may not teach a subject that is properly theological or intimately connected to theology;

- However, in lower-grade institutions he may not exercise a leadership role or a teaching function, unless the local bishop, following his prudent judgment and in the absence of scandal, discerns differently with regard to a teaching function. The same law applies to a dispensed priest with regard to religious education in institutes of the same kind not under control of the ecclesiastical authority.

- Normally, a priest who is dispensed from celibacy and all the more if joined in marriage, should stay away from the places in which his previous condition are known. But the local bishop of the place where he lives, may, after when needed having taken the advice of the bishop where the priest was incardinated or of his major religious superior, dispense from this rule of the rescript, if it can be foreseen that the continuing presence of the petitioner will not cause a scandal.

- In that case a job of pious or charitable nature should be imposed on him.

- Notification of the dispensation may either be given face to face, or through a notary or ecclesiastical secretary or through ‘registered post’. The petitioner must return one duly signed copy of the rescript to acknowledge receipt of it, as well as acceptance of the dispensation and the attached rules.

- At a convenient moment the competent local bishop should briefly report to the Congregation on the fulfilment of the notification, and if some alarm has arisen among the faithful, provide a prudent explanation of it.

(This decree will stand) notwithstanding whatever may be contrary to it.

From the office of the Congregation, 21st of February 2000.

Signed by Cardinal George Medina Estévez, Prefect, Archbishop Francis Pius Tamburino, Secretary, and V. Ferrarer, Notary.”

Assessment of the rescript

My request for release from the priestly ministry on the grounds of a conflict of conscience had been transformed into dispensation from celibacy and a reduction to the lay state. Release from celibacy was, on reflection a bonus. Moreover, there was a hidden acknowledgment of the principle ‘once a priest, always a priest’. For the reference to Canons 976, 986 § 2 meant that, in case of people needing the administration of an essential sacrament, I would not only have the right, but also the duty to exercise my priestly power.

But the overall tenor of the document was truly atrocious. It utterly lacked pastoral sensitivity.

- Where was the recognition of all the faithful services I had rendered the Church as a priest during the 39 years since my ordination? No single word of thanks.

- Where was the pastoral empathy about my conflict of conscience, of the inner turmoil that had forced me to take this unusual step?

- Where was the concern about my future, about how I would be able to make a living, about my spiritual welfare?

- Instead, was the whole emphasis not on protecting the institution from ‘scandal’, from people being upset by hearing about my misdeeds or failings as a priest?

- And then, inflicting insult upon injury, was it not bent on avoiding, at all costs, that a treacherous person like me should ‘infect’ others through my holding a teaching post in a seminary or university college?

I did get married in due course, as I will explain later. It proved a precious bonus indeed. But the experience of going through this process exposed once more the people-insensitive law-centred steam roller the institutional church had become.

Walking with interior freedom . . .

Reflecting on my situation, I decided not to take too much notice of this Vatican thunderclap. Yes, I had officially withdrawn from ministry within the Church – and some doors would remain closed. But I had not given up being a priest. As I had written in my statement: “Once a priest, always a priest. I do not intend to give up the priesthood” (see § 40). Also, in spite of Vatican prohibitions, I would continue to express my honest views as a theologian as “I owe to my own integrity and truth” (see § 39).

In other words, I decided in my conscience that Christ’s judgment of my position differed fundamentally from the stark condemnation by the official Church. Christ wanted me to continue as a priest for those who sought my help and as a prophetic teacher in a Church so badly in need of reform. That is what I have tried to do ever since.

Confirmation of the validity of this approach came years later. It happened to Fr James Alison, a priest and theologian like myself, who had also been caught in the ecclesiastical juggernaut. James had discovered that the Church’s assessment of his being gay was totally unacceptable from a theological point of view. It led to him being dispensed from membership of the Dominican Order to which he had belonged. When he sought to be incardinated in a local diocese, he did not succeed. In spite of him not having asked for it, he received the same document of ‘reduction to the lay state’ as I had done, with the prohibition to ‘teach, preach or preside’. James complained about all this in a personal letter to Pope Francis which reached the Pope because a bishop, a friend of James, gave it to the Pope in a personal audience.

And the Pope responded by speaking to James by telephone on Sunday 2 July 2017. In a long friendly conversation Pope Francis’ message came to this: “I want you to walk with deep interior freedom, following the Spirit of Jesus. And I give you the power of the keys. Do you understand? I give you the power of the keys”.

Reflecting on the implications of the message, James noted that the Pope, the ultimate authority in the Church, clearly overruled the sentence imposed by the Vatican Congregation for the Clergy. “He clearly treated me as priest, giving me universal jurisdiction to hear confessions. He was trusting me to be free to be responsibly the priest that I have spent all these years becoming. For the first time in my life in the Church I had been treated as an adult by an adult, and, good Lord!, it takes the Pope himself to act like that.” Read James Alison, ‘This is Pope Francis…’, The Tablet 28 September 2019, pp. 14-16.

Well, if this is what the Pope said to James Alison, why should it not apply to me? “I want you to walk with deep interior freedom, following the Spirit of Jesus. And I give you the power of the keys…”.

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage