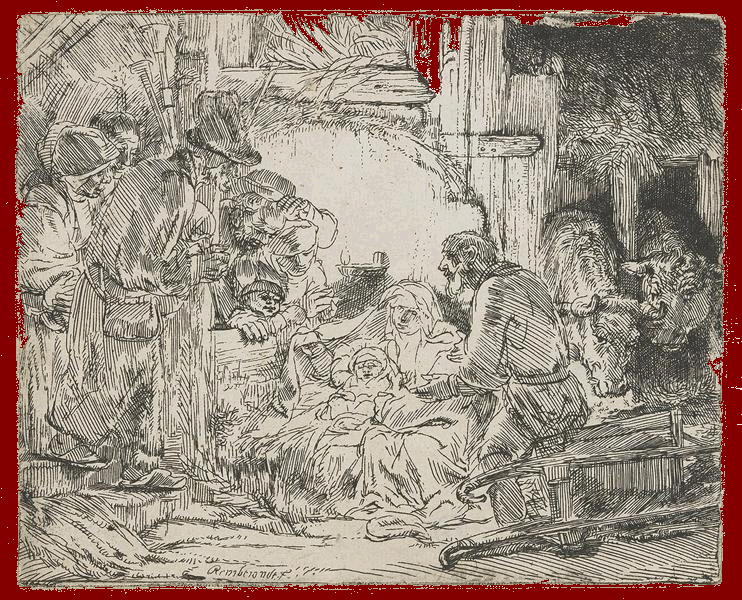

Rembrandt at the manger

by John Wijngaards, The Tablet 21/28 December 2002

When Hendrickje Stoffels, Rembrandt’s housekeeper, became pregnant with his daughter Cornelia, the artist suffered one of his severest public humiliations. The pregnancy exposed their illicit relationship, and outraged the Dutch Reformed community in Amsterdam to which Rembrandt and Hendrickje belonged. The two were summoned before the church council, reprimanded and banned from sharing the Lord’s Supper, a ban that, as far as parish records go, was never lifted. It was during the Christmas season of that same year, 1654, that Rembrandt etched his Adoration of the Shepherds with the Lamp. This is not just a pious picture. Rembrandt is giving a reply.

When Hendrickje Stoffels, Rembrandt’s housekeeper, became pregnant with his daughter Cornelia, the artist suffered one of his severest public humiliations. The pregnancy exposed their illicit relationship, and outraged the Dutch Reformed community in Amsterdam to which Rembrandt and Hendrickje belonged. The two were summoned before the church council, reprimanded and banned from sharing the Lord’s Supper, a ban that, as far as parish records go, was never lifted. It was during the Christmas season of that same year, 1654, that Rembrandt etched his Adoration of the Shepherds with the Lamp. This is not just a pious picture. Rembrandt is giving a reply.Every line is deliberate. The job took many days. Rembrandt would have drawn a number of sketches first. Then he selected a copper plate, spread his own heated mixture of wax and tree resin on it, covered it with a fine linen cloth and smoothed it down with a roller. He then carefully scratched lines into the wax with a round-pointed needle or a sharp burin, every stroke part of his statement. We can enter Rembrandt’s mind: his patient attention to detail, such as the grain on the wooden planks or the fur on the ox’s rump, and yet his preoccupation that the detail should not .be allowed to detract from the overall message. Rembrandt often redid such work six or seven times before he knew he had it right. Here everything counted.

The etching is in line with Rembrandt’s lifelong preoccupation more than any other painter in the Western world with expressing the mysteries of salvation in line and colour. While producing secular work to make ends meet, his passion lay in Scripture. A quarter of his 650 paintings and 300 etchings, and almost half of his 1,500 drawings, depict biblical scenes. This was hardly to be expected from someone who hailed from a Calvinist household, for it had been the Calvinist fury of 1566 that purged sculptures, frescoes and stained-glass windows from churches all over the Netherlands. And Calvinist iconoclasm also applied to pictures of Christ. Zwingli had said: “Since God may not be represented by images, images of Christ are also proscribed because he is truly God. If you make a picture of Christ, you are fashioning an idol and have become an Arian.” Rembrandt’s rejection of such Calvinist extremes was itself a statement against the ruling church institutions of his time. For him the whole point of Christ and Christmas is image. In the stable, adored by the shepherds, is born “the image of the invisible God” (Col 1:15).

Image of God

Rembrandt’s artistic temper demanded in any case that the object of faith be made tangible. Did John, in his first letter, not say: “Our subject is what we have heard, what we have seen with our own eyes, what we have touched with our hands, the Word who is life” (1 Jn 1:1)? No doubt Rembrandt was also influenced by his Catholic tutor, Pieter Lastman, who encouraged him to paint biblical topics. But Rembrandt remained true to his Protestant convictions in the way he did so. We can see this, most of all, in his depicting of Christ.

Between 1648 and 1661 Rembrandt painted Christ’s face at least 15 times. The baroque art of the Counter-Reformation presented Christ as a hero even in scenes depicting the Passion, where his majesty and triumphant glory still shine through. We find traces of this in Rembrandt’s earlier work, but soon the focus changed. He began to see Christ as an ordinary human being, the Son of Man, the humble servant, deeply disgraced, “without comeliness or beauty, despised and rejected by men” (Is 53:2-3). This trait is clear in The Adoration of the Shepherds. Rembrandt asserts that the mystery of the Incarnation lies precisely in the revelation of God’s love in this most ordinary of human signs: a destitute child lying on straw next to his shabbily clothed mother. Only the poorest of the poor have to find shelter in a barn, sleeping in the corner reserved for cattle. Everything in the picture bespeaks stark poverty. Just compare this stable with the contemporary Dutch interiors painted by Vermeer; and yet the child on the straw shines as the source of light, and of everyone’s faith.

Rembrandt is often praised for his brilliant use of chiaroscuro to create spatial depth. The central figures in the light become unbelievably touchable as they emerge from the dark background. But for Rembrandt the light has a deeper meaning, too. True light comes from within, and in the case of religious images, light expresses revelation: God makes himself known. The mystery of Christmas radiates from this little child in whom “the goodness and loving kindness of God our Saviour appeared” (Tit 3:4). It is not a coincidence that Rembrandt chose this scene to make his statement about the deepest meaning of Christmas. Reading Luke’s gospel, he had been struck by the fact that those invited to see the new Messiah were common shepherds. On whose side did God stand? Did God favour the respectable and prosperous merchants who paid for and controlled the boards of church elders?

Rernbrandt himself hailed from the lower middle class. His father owned a mill and his mother was the daughter of a baker. Even in his affluent years when he had bought a patrician house on the Breestraat (Broadway) in Amsterdam, Rembrandt never disowned his humble origins. Contemporary critics chide him for disregarding social convention and not seeking the company of wealthy people who, after all, were his most profitable clients: “he did not know how to keep his station and always associated with the lower orders”. In other words: Rembrandt knew himself to be a common man, and he did not bother to pretend otherwise. He rejoiced that it was ordinary people like himself who had been invited to be the first to witness the Christ event.

But there is more than this lying behind The Adoration. Perhaps the three shepherds leaning on the wooden partition just next to the child portray Rembrandt himself, his pregnant partner Hendrickje, and his 13-year-old son Titus. They have been banned from church, but here they are made to feel at home. St Joseph, seated on a wheelbarrow, takes the place of the local preacher. Instead of issuing a reprimand, he opens his hands in a gesture of genuine welcome. Perhaps he is also telling us: “See, the child is what matters. Believe in God who is Love, and all shall be well.”

Mary plays her own special role as Jesus’ mother. An ordinary, plain woman, not the triumphant Queen of Heaven of Catholic baroque art of the period, is for Rembrandt the custodian of the Word physically, in the etching. There may be an echo here of Rembrandt’s own mother, Neeltge van Suydtbroek, from whom he acquired his love of Scripture. He has more than once painted her as devoutly reading her Bible.

When Rembrandt faced bankruptcy in 1656, just two years after etching The Adoration of the Shepherds, only two books were found among his possessions: Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews and an old Bible. At his death 15 years later, he only owned one book: his well-worn Dutch Statenbijbel. Significantly, in one of the rare inscriptions next to his drawings, he characterises Mary as the one who kept God’s Word in her heart: “Admire her reverent listening which she preserved in her delicate heart to sustain the faith in her soul.” In the etching Mary lifts up the edge of her veil to uncover the sleeping child as if to say: “I trusted God and prayed: ‘Let it happen to me according to your Word’, and it has happened. See, the Word. has been made flesh.”

Standing at the crib

Rembrandt may have had a chip on his shoulder. He may have seen himself and his family, rather than the church elders, among the lowly shepherds adoring the God-with-us. He does not overemphasise this, however. His statement addresses all Christians: what matters at Christmas is meeting your God face to face in a personal, spiritual encounter. Meeting Christ at the Lord’s Supper also carried weight with him: among his paintings, etchings and drawings we have 18 separate representations of Christ with the disciples of Emmaus, appearing to them at “the breaking of the bread”.

In the polyglot and pluriform Amsterdam of his time, Rembrandt had moved well beyond exclusively Calvinist or Dutch Reformed circles. He entertained Catholic friends, consulted Rabbi Menasseh Ben Israel on details of his biblical paintings, and attended prayer services of the Mennonites, a Dutch version of Baptists. It may well have been under Mennonite influence that he came more and more to see his own religious search as an inner, spiritual, personal response to a God who even loves social outcasts.

If in our etching Rembrandt is indeed the man in the middle bending over the child with a look of faith, note that we see him taking off his cap, the typical gesture of a man acknowledging respect, the poor man’s attempt at adoration. Perhaps, in this Adoration of the Shepherds, he offers a plea to the newborn Christ, praying for acceptance, in spite of his being a sinner, and having been officially branded as such. Rembrandt drew comfort from the fact that Christ had come to give hope not to the righteous, but to sinners like himself (Mt 9:13).

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage