A lesson from History

by John Wijngaards, The Tablet 14 August 2004, pp. 10-11

Last week the Pope’s letter to the bishops again ruled out the ordination of women. But the discovery of a certain artefact suggests female deacons may well have once existed in the West.

What should the role of women be in the Church? The Pope’s letter to the bishops last week talked of partnership with men, and their vital role as part of the laity. Ordination was ruled out once more. But earlier this year, on 7 April, Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini, the retired Archbishop of Milan, called for a restoration of women deacons. The option of ordaining women to the diaconate “deserves greater recognition than is currently possible under canonical legislation”, he declared.

The ordination of women is not a new proposal. Tens of thousands of women deacons ministered in the eastern part of the Catholic Church until the tenth century. No significant parish could be without its ordained female deacon at the time when adult baptisms kept swelling the ranks of the faithful. It has always been assumed that this practice never achieved a foothold in the West. It was certainly suppressed, yes, but no foothold?

Over the past 20 years, portable baptismal fonts have been found in Britain in Ashton, Brough, East Stoke, Icklingham, Wiggenholt and Walesby. They are lead tanks, marked with either the Chi-Rho monogram denoting “Christos”, or the same monogram with the Alpha and Omega sign. The tanks are typically about a yard across in diameter and one-and-a-half feet deep, a size which corresponds to fixed stone fonts found in ancient baptisteries. Presumably the 50 lb. fonts were transported by cart from location to location. The neophyte would stand knee-deep in the water which was scooped up and poured from the head down over the body. Scenes of fourth and fifth century Christian baptisms confirm this practice. They show the neophyte standing in a small tank or basin while water flows from his or her head.

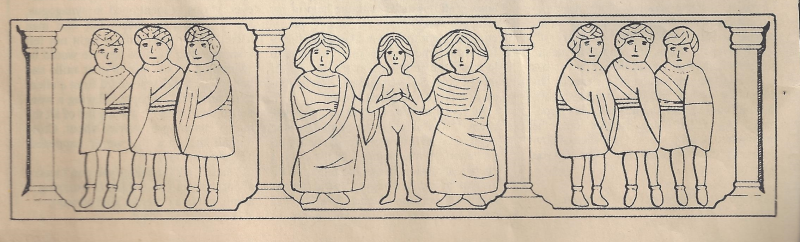

The Walesby tank provides even more detail. On the outer wall of the tank, running just below the rim, is a unique relief of human figures (see Charles Thomas’s reconstruction below). Three of the panels have been preserved. The left and right panels show men in cloaks and tunics. The middle panel displays a naked woman flanked by two thickly veiled and draped ladies who hold her by her arms. It is clear that the scene portrays baptism which, in those days, involved a stripping of all clothes, an anointing over the whole body with oil and a baptism that cleansed all the limbs. Modesty was the reason why, as we know so well from eastern sources, it was women deacons who assisted at the baptism of women.

Research has identified the ordination prayer for women, testified to by 11 manuscripts from Germany arid Gaul

Were the two heavily robed ladies seen with the neophyte such women deacons? The Walesby picture by itself cannot be conclusive on this point. It could be argued, as some historians have done, that they were sponsors presenting a friend for baptism. But where is the priest to whom she is presented? And why would sponsors present j their friend naked? I prefer the other interpretation, which accepts a baptism of women by women. The women seem deliberately presented in a separate enclosure. The group is probably standing in the baptismal room and the two women face the j neophyte as they would do during an actual baptism at the moment they undress her. The frontal presentation of all figures is typical of contemporary fifth-century art.

We know little about the small Christian communities that existed in early Britain. They may have had distinctive Celtic features that were drowned under the invasion of the Angles and Saxons, and by the influence of St Augustine and his Roman missionaries. Many literary sources have been lost, or re-written to conform with later Roman regulations. St Patrick was a native Briton. His originality in shaping Christian faith and practice in Ireland bears testimony to a strong non-Roman component in his own brand of Christianity. For one thing, women enjoyed a higher position, as the records of St Bridget of Kildare and St Hilda of Whitby demonstrate.

Was the institution of women deacons known to the Romano-British Church? It must have been. The Council of Chalcedon implicitly sanctioned women deacons when it prescribed a minimum age of 40 for them. Their status and rights among other ranks of the clergy had been laid down in the religious laws of Emperors Theodosius and Justinian I. The fifth-century monk Pelagius, who was born in Britain, remarked on the spread of women deacons in the East, implying perhaps that the practice was not common in Britain. On the other hand, he comments favourably on the three New Testament passages that mention women deacons.

More evidence comes, surprisingly, from across the Channel in Gaul. St Remigius, apostle of the Franks and Archbishop of Reims, praises his daughter Hilary, the deaconess. And we read in an ancient source, that Bishop Medardus of Noyon “consecrated Radegunde as a deacon by imposing hands on her”. St Genevieve, patron of Paris, ministered as a deacon. These women usually belonged to a religious community, but their ordination was not identical, at least at this time, to taking the habit. Only certain nuns were ordained to be deacons and then because of their ministry. All this while one Gallic local synod after the other tried to suppress the practice. The Second Synod of Orleans (533) stated: “It has been decided that from now on diaconal ordination will not be given to any woman because of the fragility of their condition.” It indicates the reason for opposition to women’s ministry in Roman circles. By Roman law women are excluded from leadership, and women’s sexual weakness makes them a constant source of temptation for men.

So witness the reaction in Gaul when barbarous Britons, fleeing the Saxon advance, cross the channel and settle in present-day Brittany. A letter from the bishops of Tours, Rennes and Angers dated 520 accuses two Britons, both priests, Lovocatus and Cahemes, of introducing female ministers: “We have learnt that, bearing certain portable altars, you do not cease from making a circuit of the dwellings in the territories of different cities, and that you presume to celebrate Masses there with women, whom you call conhospitae [joint hostesses] and whom you involve in the divine sacrifice to such an extent that while you distribute the Eucharist they hold the chalice in your presence and presume to administer the blood of Christ to the people.” A dreadful crime indeed, revealing a glimpse of uncivilised Celtic Christianity!

Research in ancient Latin sacramentaries has now identified the original ordination prayer for women deacons, oratio ad diaconam faciendam. It is testified to by 11 manuscripts from Gaul and Germany. The prayer is unisex. It is found in a masculine form, to ordain male deacons, and a feminine form, to ordain the women. Both prayers are identical in every single word, except for the masculine and feminine endings. This is its text: “Hear, O Lord, our prayers and pour the Spirit of your ordination on this servant of yours, so that enriched by your heavenly gift, she may acquire the j grace of your majesty and give the example of a good life to others. Through Christ Our I Lord, etc. It was accompanied by the imposition of hands, and the handing over of a stole and Gospel book. The male formulation of the prayer has remained part of the diaconate ordination rite in spite of the addi tion of a second ordination prayer, the preface, to the rite in later centuries.

Authorities in Rome are in a cleft stick regarding the ordination of women deacons. Historical evidence documents truly sacramental ordination of women to the diaconate during the first millennium. But the sacraments of the diaconate and the priesthood are intimately linked, as an ambivalent report by the partisan International Theological Commission pointed out in November 2002. So if women have been ordained deacons, they are capable of receiving holy orders, something the above- mentioned authorities are loath to admit.

Why deny historical fact, I cannot help asking myself. Why whitewash the true reasons for which women were gradually pushed out of the ministries? Why reject sincere but critical scholarship? For surely, “the truth shall make you free”.

*** John Wijngaards is director of the Housetop Centre for Adult Faith Formation, and the author of No Women in Holy Orders? The Women Deacons of the Early Church, Canterbury Press, 2002. Supporting evidence can be found on www. womendeacons.org

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage