GUEST EDITORIAL

PRAYER FOR GUIDANCE: AN ATTITUDE COMMON TO CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS

by John Wijngaards, THE MUSLIM WORLD, Hartford Seminary Foundation, LVII, No. 4, 1967, p259-264

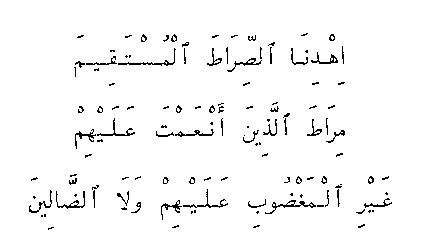

In the Opening Sura of the Qur’ān the prophet Muhammad places the following concluding words as a daily prayer for his followers:

With J. M. Rodwell we interpret this prayer to mean:

“Guide Thou us on the straight path,

the path of those to whom Thou hast been gracious,

with whom Thou art not angry,

and who go not astray!”[1]

Taking this prayer as the starting point of our investigation, some noteworthy and important historical as well as theological connections between Christianity and Islam can be illustrated. Perhaps this choice of subject is a daring one. I am aware of the immense wealth of research and theological thought that must already have been devoted to this prayer. I am deeply conscious of my own insufficient acquaintance with the huge complex of Islamic studies. When dealing with the topic I felt my incompetence to judge many of its aspects. And yet, in spite of all these dissuading considerations, I decided to put forward’ my modest observations, hoping that I may be able to make a small contribution to the dialogue between Islam and Christianity. One of the limitations of our present world is over-specialization. The competence of scholars has increasingly been limited to ever smaller fields of research. This specialization ensures authoritative and efficient study in any branch of science, but at the same time it seriously endangers the fruitful exchange of experience with other branches of that science. If Christian or Islamic scholars were never to overstep the boundaries of their own theologies, what dialogue would be possible? If our judgments and statements were to remain strictly confined to our own field of competence, what room would be left for searching and probing, for question and answer, for a wider and therefore truer horizon? If competence is over stressed, how can religious men grow together in their search for a common attitude towards the One, True God, the Creator, the Father and the Judge of all mankind? For these reasons I thought to be justified in partly overstepping my competence. I humbly request my readers to pardon the deficiencies that may appear in my exposition, and I kindly invite them to bring forward the modifications and corrections, the clarifications and additions which their scholarship allows them to make. It is as a spark to light thought and mutual discussion – as a means of opening the window to better understanding and closer cooperation – that I sincerely wish this present paper to serve.

Introduction: The Prayer-formula in the dialogue of Christians and Muslims during the Middle Ages.

From the beginning of Islam contact between the Christian world and the carriers of the new Islamic message led to frequent discussions and debates. As early as A.D. 639 General ‘Amr Ibn aI-cĀs conducted official talks with John the First, the Nestorian Bishop of Antioch; and four years later he approached Benjamin, the Jacobite Patriarch of Egypt, for the same purpose. The outcome of their debates was carefully noted and the text has been preserved.[2] After that a steady flow of apologetic books of Muslims[3] and Christian[4] origin appeared until the end of the Middle Ages. Among the Christian writers we find theologians such as John of Damascus, Theodore Abū Qurra, Peter the Venerable, Raymund Lullus, Raymund Martini, Ricoldus da Monte Crucis, and even the great Saint Thomas Aquinas. The Muslim apologists count among their ranks such outspoken figures as al- Ṭabarī, Qasim al-Ḥasanī, al-Jāḥiẓi, Ibn Ḥazm, Jālih al-Gha،farī, al-Qarāfī, Ibn Taimīya and Muḥammad Ibn Abi Ṭālib.

In the first half of the thirteenth century the prayer-formula of the first Sura made its entrance into this world of polemics. The Melkite Bishop of Sidon, Paulus al-Rāhib, produced a small treatise called “Risāla ilā aḥad al-muslimīn”[5] in which he proposed a rather bold interpretation of the last verses of Sura I. He maintained that the supplication should be read in this manner: “The path of those to whom God has been gracious” stands for the Christian revelation; the reference to ‘those with whom God is angry and who go astray’ is to the Jews and the pagans respectively. He concludes, therefore, that Muslims in actual fact pray to become Christians whenever they say: “Lead Thou us on the straight path, the path of those to whom Thou hast been gracious”! He goes on to say that the very fact of praying for guidance implies the admission that the supplicant is still in error!

Ahmad Ibn-Idrīs al-Qarāfī, who died in A.D. 1285, did not find it difficult to reply to this rather naive argument. In his essay ‘”AI- ajwiba al-fākhira ،an al-as’ila al-fājira” (Precious Answers to Scandalous Questions)[6] he points out that forms of speech such as prohibitions, orders, requests and demands do not exclude the actual state or condition. When a Muslim prays: “Lead us on the straight path”, the request presupposes his actually being on the straight path. A Christian uses a similar language when he prays: “Let me die in my religion!”

In the year A.D. 1321 the apologetic letter composed by “the bishops and patriarchs, priests and monks” of the island Cyprus revived many of Paulus al-Rāhib’s arguments. Although this writing can be only partially reconstructed, it seems quite certain that the pro-Christian interpretation of Sura 1 verses 5-7 was restated in its old form. Popular arguments like this one appeal to the imagination; they are rarely relinquished with ease! [7]

The following year saw the Muslim reply in a voluminous work entitled Al-jawāb al-ṣaḥīḥ liman baddala Dīn al–Masīf (The truthful Answer to those who falsify the religion of the Messiah).[8] The author, ،Abdu’l ،Abbas Aḥmad Ibn Taimīya, rejects the pro-Christian interpretation of the prayer-formula. Did the prophet Muhammad not teach the unbelief of the Christians (Qur. 5: 77, 19; 9: 30)? How could he then say: “Lead us on the path of the Christians!”? No, the prayer-formula has to be seen in the light of Sura 4: 71 where the propehet Muḥammad exclaims: “Whoever shall obey God and the Apostle, these shall be with those of the Prophets, and of the Sincere, and of the Martyrs, and of the Just, to who God has been gracious” are clearly identified with “the Prophets, the Sincere, the Martyrs and the Just”! Saying: “Lead us on the straight path, the path of those to whom Thos hast been gracious”, we pray to be allowed to follow the footsteps of these saintly people.

The Ṣūfī scholar from Damascus, Muḥammad Ibn Abi Ṭālib al-Anṣārī, also replied to the objections of the Cypriotic letter in “Jawāb risālat ahl jazīrat Qubrūs”.[9] With reference to the prayer for guidance on the straight path he proposes a threefold explanation: first, the Muslim prays for guidance out of religious zeal in order to obtain more grace; secondly, he prays in this way to be preserved from being led into error and sin by the devils; lastly, the prayer aims at improving interior recollection. In other words the prayer for guidance on the straight path concerns self-sanctification. By saying this prayer one merely acknowledges one’s need of God’s help to remain faithful.

What interests us most in these discussions is the interpretation given to verses 5-7 of the Fātiha by scholars such as al-Qarāfī, Ibn Taimīya and Muḥammad Ibn Abi Ṭālib. It is apparent that these scholars of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries explain the prophet Muḥammad’s prayer for guidance in a general and universal sense. “Lead Thou us on the straight path” means “lead us on the path of your saints”, “lead us to sanctity”, “guide us away from diabolic temptation and error”, “guide us in our life of prayer and recollection”. No doubt, they are firmly convinced that this straight path, this path of truth and sanctity in actual fact is to be found in Islam. But nowhere do they claim that the words of the prayer themselves are directed against other religions such as Judaism and Christianity.

The question is not without importance. Two of the most popular commentaries of the Qurᵓān, the one by al- Baiḍāwī (died I300 A.D.) and the other by al-Jalālayn (died I459, I505),[10] give a notably different version. They maintain that the last phrases of the petition are directed against these two religions. The clause “with whom Thou art not angry” distinguishes according to them the right path from the path followed by the Jews with whom God is angry. Moreover, the words “‘those who go astray” are understood to signify the Christians who went astray from the true doctrine of our Lord Jesus Christ. In this interpretation the prayer-formula itself has the very restricted sense of excluding Judaism and Christianity.

ᶜAbdul Qādir al- Jīlanī (died 1166) agrees with these commentators in as far as he refers “those with whom God is angry” to the Jews. He leaves it an open question whether Christians should be included too. But al-Zarnakhsharī (died 1144) in his commentary al-Kashshāf ᶜan hoqāᵓiq al-tanzīl denies any negative meaning to the statement. He renders the passage in this way:

“Guide Thou us on the straight path,

the path of those to whom Thou hast been gracious,

the path of those against whom Thou art not incensed,

the path of those who go not astray.”

In this translation the whole passage refers to the true believers. The prayer formula then expresses the petition that God may guide the supplicant on the path of all the saintly and believing predecessors, the martyrs, prophets, righteous and just. The passage itself would not be directed explicitly against Jews and Christians.[11]

Comparison with other Qur’anic texts favours this last explanation. The expressions “to be gracious to”, “‘to be angry with” and “to go astray” are not fixed terminology, but apply to many different situations. God’s favour and graciousness are said to be with Adam, Noah, Abraham, Ishmael[12], with Kaleb and Joshua[13], with all the prophets, saints, martyrs and just[14], with the followers of the prophet himself[15], but also with the children of Israel[16], and the Christians[17] taken as groups. God’s anger does not only punish unbelievers[18], but also those among the believers who in their pride refuse to give alms[19], who oppress orphans[20], who indulge in usury[21], who conclude marriages with relatives within the forbidden degrees[22], or who waste time on gambling[23]. Similarly we find that in the Qurᵓān phrases such as “to err” or “to go astray from the path” are applied to the most diverse groups of people. Usually we find these expressions referring to idolaters, such as the idol-worshippers of Mecca[24] and the Queen of Saba[25]. The phrases are also applied to those who believe in the One God, but who refuse to accept the new revelation; among them are .Djinn[26], Jews[27] and Christians[28]. Moreover, the phrases equally apply to those who err by any sin; they refer to Adam’s sin of disobedience in paradise[29], Moses’ murder of an Egyptian[30] and David’s act of adultery with Bathsheba[31]. The general sense of the expression is borne out by statements like: “Hell shall lay open for those who have gone astray.”[32] In other words, “‘to go astray from the path of ‘God” is a Qur’anic way of defining all sins which eventually lead to eternal punishment.

From this internal evidence of the Qurᵓān, supported by Muslim scholars such as al-Qarāfī, Ibn Taimīya, Muhammad Ibn Abi Tālib and al-Zarnakhsharī, we conclude that the prayer-formula of the Fātiha does not have a restricted or negative sense. We conclude that’ the formula expresses the request that God may guide the petitioner in the way of true faith and true virtue, in the way of His prophets and saints. The prayer is not purposely directed against Jews or Christians. The supplicant merely asks that God may preserve him from going astray from the path of sanctity through unbelief or sinful conduct. It is a prayer for God’s guidance to the right religion, to a saintly life, and eventually to heaven.

PRAYER FOR GUIDANCE: ORIGIN, HISTORICAL

BACKGROUND AND MEANING

Reprinted from:

THE MUSLIM WORLD

Hartford Seminary Foundation, LVIII, No. 1, 1968, p1-11

What then did the formula “Guide Thou us on the straight path” convey to the prophet Muḥammad and to his contemporaries? In what circumstances was it employed? Did the formula already enjoy a distinct religious meaning at the time of its appearance in the Fātiḥa? Can we trace its history in time and place? In order to find an answer to these questions, we will study the origin and meaning of the same formula in the Old Testament.

No one acquainted with the modern study of the Old Testament can ignore the benefit derived from understanding technical phrases or literary forms in the light of the historical setting (the Sitz-im-Leben) in which these phrases or literary forms originated. Herman Gunkel deserves much praise for having illustrated for the first time how some Psalms were at home in the thanksgiving service after illness and in private devotions, others in public lamentations and personal difficulties.[33] The prophetic writings were similarly clarified by the discovery of literary forms such as the “Botenspruch,” the song of mourning for a deceased person, covenantal rīb and the pledge of’ a future covenant.[34] In all such cases it was found that in certain, well-defined situations of life fixed formulations, fixed ways of speaking and writing were employed. Much reflection is not necessary to see how natural this process of terminological fixation is. Doesn’t our correspondence follow a rigorously determined pattern and do not our letters abound with frequently repeated formulations? In many cases the meaning and value of such accepted formulations may be self-evident;

in other instances they may not be fully understood when separated from their historical setting. In a stimulating article Daube has illustrated this principle with many examples. God’s taking Abraham to a high place, showing him all the land and saying: “All this I will give to you” (Gen. I3: I4-I7), is of more significance if we know that this was the accepted way of transferring landed property to a new owner! Adam’s exclamation “This is bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh” (Gen. 2: 23) appears to be the central phrase in a ceremony of adoption. When God demands from Pharaoh: “Let My son go” (Ex. 4: 23), He employs the technical formula of a juridical claim on a newly acquired slave.[35] Having gained insight into the historical setting that gave rise to fixed formulations, the technical meaning, the precise contents, the subtle connotations of these expressions will less easily escape us.

What is the historical setting of the phrase “Guide Thou us on the straight path”? In the eighth chapter of the Book of Ezra we read that the Jews were permitted by the Persian King to return to their native country. Before they set out on the long and dangerous journey from Babylon to Palestine they kept a fast and arranged for special prayers. The aim of these ceremonies was “to seek from God a straight path for ourselves, our children and our goods.” The whole passage reads as follows:

“Then I proclaimed a fast there, at the river Ahava, that we might humble ourselves before our God, to seek from Him a straight path for ourselves, our children and all our goods. For I was ashamed to ask the king for a band of soldiers and horsemen to protect us against the enemy on our way; since we had told the king: ‘The hand of our God is for good upon all that seek Him, and the power of His wrath is with all that forsake Him!’ So we fasted and besought our God for this, and He listened to our entreaty.” (Ezra 8: 2I-23).

Here we have a valuable indication. The phrase “Guide us on the straight path” is the central entreaty in a prayer-ceremony arranged at the undertaking of a long journey!

Psalm 107 confirms the function of the formula. In this thanksgiving psalm God’s favor bestowed on travellers is recalled. Having lost their way in the desert, they arrange for a special prayer ceremony. God listens to their entreaty and guides them by a straight way.

“Some wandered in desert wastes, finding no way to a city to dwell in; hungry and thirsty, their soul fainted within them! Then they cried to the Lord in their trouble, and He delivered them from their distress; He led them by a straight way, till they reached a city to dwell in.” (Ps. 107: 4-7).

In other words: God delivered them by granting the immediate

There is more evidence from the Old Testament regarding this prayer ceremony at the outset of a long journey. It would seem that originally three distinct phases were contained in it:

- The prayer for guidance on the journey;

- The oracle of a priest (or later a blessing) reassuring the traveller of God’s guidance;

- The thanksgiving prayers after successfully completing the journey.

Jacob’s journey may serve as an example. Before leaving for Chaldea he makes the following prayer and vow: “If God will be with me, and will keep me in this way that I go, and will give me bread to eat and clothing to wear, so that I come again to my father’s house in peace, then the Lord shall be my God, and this stone which I have set up for a pillar, shall be God’s house.” (Gen. 28 : 20-22).

In a dream Jacob is reassured of God’s guidance by a divine oracle:

“I am the Lord, the God of Abraham your father and the God of Isaac. The land on which you lie I will give to you and to your descendants … Behold, I am with you and will keep you wherever you go, and will bring you back to this land.” (Gen. 28: 13, 15). Returning after more than fourteen years Jacob had not forgotten his vow taken before setting out on his journey. He exhorts his kinsmen saying:

“Put away the foreign gods that are among you … and let us arise and go up to Bethel, that I may make there an altar to the God who answered me in the day of my distress and has been with me wherever I have gone.” (Gen. 35: 2-3). We will subject each of the three elements – prayer, oracle and thanksgiving – to a short examination.

Psalm 139 is a prayer of a man going on a journey. Commentators are somewhat at a loss to explain how the philosophical reflections on God’s omnipresence and omniscience in the first eighteen verses can be harmonized with a supplication against enemies in the last six verses.[36] In the historical setting of the journey this difficulty does not arise. It is only natural for the supplicant to reflect on the fact that God will be with him whatever distance his travel might take him:

“Whither shall I go from Thy Spirit? or whither shall I flee from Thy presence? If I ascend to heaven, Thou art there! If I lie down in the underworld, Thou art there! If I take the wings of the morning and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea, even there Thy hand shall lead me, and Thy right hand shall hold me.” (Ps. 139: 7-9)

No wonder, however, that the prospect of encountering robbers and brigands makes him say: “0 that Thou wouldst slay the wicked, 0 God, and that men of blood would depart from me.” (Ps. 139: 19). The Psalm ends with the traditional prayer for guidance: “Guide me in the ancient path” (vs. 24). The ancient path is the reliable way that has proved safe and comfortable, as other Scriptural passages illustrate. [37]

In many other psalms we find quotations or metaphors borrowed from the prayer of the traveller. In a supplication against false witnesses we read: “Lead me, 0 Lord, in Thy righteousness because of my enemies; make Thy way straight before me.” (Ps. 5 : 8).

The metaphor of guidance on a journey is sustained all through Psalm 25. The phrase, “teach me Thy Ways”, recurs in many prayers.[38] At times it is difficult to determine whether the references are to a real journey or to the path of virtue. In Ps. 143 the supplicant exclaims:

“The enemy has pursued me; he has crushed my life to the ground!” (Ps. 143: 3).

After briefly recalling God’s help in the past he continues: “Deliver me, O Lord, from my enemies! I have fled to Thee for refuge! Teach me to do Thy will, for Thou art my God. Let Thy good spirit lead me on a level path!” (Ps. 143 : 9-10)

From these examples one can rightly deduce that in ancient Israel some kind of prayer-formulary for travellers was in common use. This formulary contained phrases such as: “Lead me in Thy righteousness,” “Let me know Thy way,” “Guide me in the ancient path” or “Guide me on the straight path.”

In Old Testament times travelling for pleasure was practically unknown. Journeys had definite aims, such as business, exchange of political messages, warfare, settling family affairs. Travel belonged to the category of necessary evils. Faced with the prospects of all possible dangers and mishaps on his way, the traveller would turn to a priest or a prophet for an oracle on the advisability of undertaking the journey. So we read in the Old Testament that Saul approaches Samuel,[39] the Danite spies interrogate the priest in Micah’s house,[40] Kings Jehoshapat and Jehoram seek God’s word from Elisha[41] and Balaam refuses to go with Balak’s ambassadors without a favorable oracle from the Lord.[42]

- Begrich has shown that in such instances the priest or another spokesman on Jahweh’s part could give a reassuring oracle, an oracle that was, perhaps, given at the end of the ceremony of supplication.[43] The priestly oracle for travellers may, in the course of time, have taken on definite formulations. As an example of such formulas we might mention the oracle of Micah’s priest: “Go in peace. The journey on which you go is under the eye of the Lord.” (Judg. 18: 6).

In a slightly different form Psalm 32 states the same: “I will instruct you and teach you the way you should go. I will counsel you with My eye upon you.” (Ps. 32 : 8). Isaiah quotes a priestly oracle when he says: “Your ears shall hear a word behind you, saying: ‘This is the way, walk in it’ when you turn to the right or when you turn to the left.” (Is. 30 : 21).

In this last oracle God’s promise concerns guidance on the straight path, i.e. not allowing deviations to the right or to the left. In the announcement of the return from exile, Deutero-Isaiah frequently frames God’s statements in the wording of such priestly oracles:

“I will lead the blind in a way that they know not, in paths that they have not known I will guide them … ” (Is. 42 : 16).

“He who has pity on them will lead them, and by springs of water He will guide them … ” (Is. 49 : IQ ff).

“All his ways I will make straight.” (Is. 45: 13).

Jeremiah also employs the same imagery and formulations:

“I will make them walk by brooks of water, in a straight path in which they shall not stumble.” (Jer. 31 : 9).

Closely related to these oracles are blessings spoken over the traveller. Psalm 91 has preserved a long blessing which may originally have been meant for pilgrims on the point of returning home from Jerusalem. One passage reads:

“He will give His angels charge of you, to guard you in all your ways. On their hands they will bear you up, lest you dash your foot against a stone.” (Ps. 91 : 11-12).

And the Book of Tobias records the reassuring words:

“Do not be troubled… He will come back safe and sound, and your eyes shall see him. For a good angel will go with him, and he will have a prosperous journey, and will come back safe and sound.” (Tob. 5 : 21). [44]

Corresponding to the traveller’s supplication there existed, consequently, formulations of priestly oracles and blessings reassuring the supplicant of God’s favor on his path. Among these formulations we find the phrases: “I will guide them in a path they don’t know,” “All your ways I will make straight” and “I will make them walk in a straight path.”

The thanksgiving after the journey must also have belonged to the common practice of the day. Instances of this practice may be seen in the prayers of Jacob[45] and Eliezer,[46] in the gratitude of young Tobias[47] and the chorus of Psalm 107. Again the formula of “guidance on the straight path” is employed, here in the sense of indicating the main reason for gratitude. Eliezer exclaims: “Blessed be the Lord, the God’ of my master Abraham, who has not failed to be gracious and true to my master. I am on the right road; The Lord has led me to the home of my master’s kinsfolk.” (Gen. 24: 27).

Later he narrates to Laban: “I bowed in homage to the Lord, blessing the Lord, the God of my master Abraham, who had led me by the right road … ” (Gen. 24: 48).

Psalm 107 declares in one breath: “The Lord has guided them in a straight way ... Let them thank the Lord for His kindness!” (Ps. 107: 7-8).

In all the phases of the prayer-ceremonies surrounding travelling we encountered the formula “guidance on the straight path,” whether in the prayers at the outset of the journey, in the reassuring oracles and blessings, or in the thanksgiving after reaching the destination. We are justified in stating that the formula originated in the historical setting of travel. Collating all the texts employing the formula we discover a wide and elastic range of meaning. “Guiding on the straight path” does not only – as we might expect – signify “preservation from swerving into by-paths or from losing the way”[48] but also “guidance on the ancient path,”[49] “protection against enemies,”[50] and “granting stability against slipping or stumbling on the road.”[51] As a central or key formula “guidance on the straight path” embraces safe conduct through all possible misfortunes, necessities and perils. Thus the transition from the profane sense to an application of religious contents could easily be made!

“Guidance on the straight path” now came to indicate support in repelling seducers, in escaping sin, in understanding God’s mysteries and obeying His commandments.[52] It is in this connection that the proverb “The fool’s way is straight in his own eyes”[53] should be mentioned, since it bridges the profane and the religious significations of the formula. “Those going straight” becomes synonymous to “virtuous men.”[54]

Proceeding from the Old Testament days to the time of the prophet Muhammad, we find that the formula of guidance has lost nothing of its directness. Travelling for business, for politics or for the sake of pilgrimage was in full swing. Research on the history of liturgical prayer has shown that travel enjoyed considerable interest in the eyes of the Christian Church.[55]

Hospitality was a virtue frequently mentioned in sermons; travellers were made the object of supplication in litanies; special accommodation for guests was provided in the monasteries. Many liturgical rites and ceremonies were known: thanksgiving when receiving a traveller, supplications during the sacred rite of Mass, but especially the liturgical function of prayer before setting out on a journey. We will quote from these prayers, in order to show how the formula of guidance is applied both to the immediate need of the journey and the spiritual need of a man’s path in virtue:

“May the God of our salvation make our way prosperous before us!

Show us Thy mercy, O God – and teach us Thy paths! O, that our ways may be directed – to keep Thy righteous laws!”

Or again: “May the Almighty and Merciful Lord guide us on the path of peace and safety … that in peace, salvation and joy we may return home!”

Or more at length: “Be to us, O Lord, protection in danger, our comfort on the road, our shade in heat, our shelter in rain or cold, support in tiredness, a shield against enemies, a staff on slippery soil, a harbor in the tempest … guide the way of your servants to the safety of salvation: that in all dangers of our travel and our life we may always reckon on your protection !” [56]

Such prayers were frequently in the mouths of Christians in Muhammad’s time. And, as might be expected, Old Testament practices concerning travel also remained in honor with the Jews. A very common prayer would seem to have been an entreaty of Psalm 5 : 9 and Psalm 26 : 11 combined, which runs as follows: “Lead me, O Lord, in Thy righteousness because of my enemies; make Thy way straight before me! As for me, I (try to) walk in integrity; save me and be gracious to me!”[57]

The prophet Muhammad may have been present at such ceremonies of supplication before starting a journey. From his biography we know that in his early years he had travelled frequently. The Qurᵓān witnesses to a deep travel consciousness. Often God is especially praised for enabling man to travel through His creation:

“God has spread the earth for you like a carpet, that ye may walk therein along spacious paths!”[58]

“He has made the earth as a couch for you and has traced out routes therein for your guidance!” [59] There are other parallel expressions.[60] God is acknowledged to be the one who can alone save the wayfarer: “Is not He the one who guides you in the darkness of the land and of the sea?”[61] Generosity towards travellers is prescribed[62] and individual journeys such as the one of Moses[63] and Dhu’l-Qarnain[64] are described in detail. Moreover, the Qurᵓān makes explicit mention of the liturgical ceremony of travellers starting on a journey or finding themselves in special danger:

“When a misfortune befalls you at sea, the idols whom you invoke are not to be found! God alone is there: yet when He brings you safe to dry land, you place yourself at a distance from Him!”[65]

And again with a clear reference to the ceremony of thanksgiving:

“Are you sure that He will not cause you to put back to sea a second time and send against you a stormblast, and drown you for that you have been thankless?”[66]

The prophet Muhammad and his contemporaries, therefore, were well acquainted with the prayer ceremonies of the Jews and the Christians before, during and after travelling. There is nothing more natural than to suppose that all members of a caravan were requested to join common ceremonies. With these facts in mind I conclude that the prayer-formula for guidance found in the Opening Sura of the Qurᵓān should be understood in the light of the Old Testament phraseology used in these ceremonies. Even granted the direct inspiration of the Qurᵓān by immediate dictation of God, as the traditional Islamic view holds, it will not be denied that God will have used words and phrases that were known to the prophet and his contemporaries. Whether the Qurᵓān, therefore, be taken to be inspired or not, the peculiar background and meaning of the formula for guidance must be taken into consideration when explaining the Fātiḥa. The formula for guidance on the straight path – so well known to the prophet Muhammad’s con- temporaries from the historical setting of travel – was now, precisely as in the Old Testament and Christian prayer, applied more broadly to include the spiritual realm, man’s journey through the vicissitudes of this life towards heaven.

Conclusion: The Prayer for Guidance, a Link between Christianity and Islam.

In the introductory part of this paper we showed how the formula of guidance on the straight path played a part in the early dialogue between Christianity and Islam. In our discussion of the origin and historical setting of this formula we discovered a far more fundamental reason to accept it as a link between these two religions. This link was proved to be more than similarity or parallelism, but born from social and religious contact. Having established these facts, we may now reflect on their significance.

It is beyond dispute that Islam and Christianity differ widely in their religious beliefs. To try an amalgamation of these beliefs would be both impracticable and unacceptable to Muslims and Christians alike. Dialogue should, however, continue to break down unnecessary barriers of prejudice on both sides. And in this dialogue the prayer for guidance could play an important role. Whatever their differences, Christians and Muslims and Jews all pray for God’s guidance; in fact, they employ what can historically be shown to be the same prayer. Muslims, Jews and Christians when speaking this prayer for guidance, have more in common than the superficial sound of words: they all share the basic faith in a God who revealed Himself to man and who calls man to an eternal destiny. The author of the letter to the Hebrews gives the following description of believing men, which could equally be applied to Jews, Muslims and Christians:

“They have acknowledged that they were strangers and exiles on the earth. For people who speak thus make it clear that they are seeking a homeland … yes, they desire a better country, that is, a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God, for He has prepared for them a city.” (Hebr. 11 : 13-16).

In face of agnostic materialism, so rampant in many parts of the world, this common belief in God’s guidance can provide a valuable basis for mutual appreciation and united action in various charitable, social and religious fields of life. Our dogmatic differences are real; but is our common trust in God’s merciful guidance not equally real?

The acknowledgment of our common attitude towards the God of revelation has, moreover, practical implications. Since we are all brothers and sisters of the same human family, since we all share love and reverence for our heavenly Father, should we not join in common prayer? Should Muslims and Jews and Christians not offer combined praises and thanksgiving to the One God, the Creator, Father and Merciful Judge of all?

I am of the opinion that it might not be practicable nor advisable to encourage an indiscriminate mixing in the public ceremonies of worship celebrated by the three great religions. Participation in such a public ceremony presupposes full belief in the religion celebrated, and is understood as a profession of faith in that belief. But some immediate practical steps might be taken to bring Christian and Muslim nearer in prayer:

- In the liturgical prayers of our communities the adherents of the other religion should be more frequently and more earnestly commemorated. In local Christian communities, especially in places where Muslims form a considerable part of the population, much more could be done in this respect. Moreover, many Christians would appreciate it very much if they were commemorated in the public prayers of the Muslims.

-

- Whenever the occasion presents itself, individual Muslims and Christians could join in common prayer. There may be families where husband and wife or other members belong to these different religions. Could they not formulate one common prayer and so express their united attitude towards the Merciful Father in heaven? When Muslims and Christians meet at table, could they not say grace before and after the meal in a joint prayer? In all such cases, the circumstances have to determine the advisability and the extent of sharing prayer. But in principle, I feel, we should not hesitate to realize such prayer where it is possible.

</ol

The highest union with God, the most perfect form of prayer is undoubtedly reached by the mystics. And it is in the Christian and Muslim mystics that Christianity and Islam have approached each other more than in any other area. Prayers of Muslim and Christian mystics are often so similar that they could be interchanged. Who of the great Christian mystics could not have exclaimed with the Muslim saint Dhu’l-Nūn: “O my God, I desire you! For you in my heart a place is kept! All reproach is indifferent to me, since I love you! For your love I wish to be a victim … “? John of the Cross, Theresa, Ruusbroeck and so many others have spoken these same words. The reason for this similarity is a profound theological truth. Mystics are men who allow God to guide their lives. They are so obedient, so sensitive to His lead that – as they themselves tell us – it is He Himself who lives in them. If these Christian and Muslim mystics were to have met, would they have experienced difficulty in praying together? I am sure they would not. Does there not seem to be something wrong with us and with our prayer if we cannot harmonize? Is there, perhaps, too much of ourselves, too little of God’s guidance in our mentality and our manner of praying? If in true humility we ask God to guide us, to take over in us, to live in us, Muslims and Christians will find one another in prayer.

When Pope Paul VI, the Head of the Roman Catholic Church, came ‘to Bombay in December 1964, he went out of his way to meet the non-Christian religious leaders of India. I would like to conclude with a quotation from the words which he spoke on that occasion. I hope that the desire he expressed may be prophetic of what the future will see realized:

“We must come closer together, not only through the modern means of communication, through press and radio, through steamships and jet planes – we must come together with our hearts, in mutual understanding, esteem and love. We must meet, not merely as tourists, but as pilgrims who set out to find God … !” [67]

Hyderabad, 13, India. J. N. M. W1JNGAARDS

[1] J. M. Rodwell, The Koran (London, 1909, repr. 1953) p. 28.

[2] F. Nau, “Un Colloque du Patriarche Jean avec l’Emir des Agareens … ” . Journal Asiatique, II (1915), 225-267.

[3] cf. A. Palmieri, Die Polemik des Islams, Salzburg, 1902.

-

-

- Fritsch, Islam und Christentum im Mittelalter. Beiträge zur Geschichte der muslimischen Polemik gegen das Christentum in Arabischer Sprache, Breslau, 1930.

-

A.T. van Leeuwen, Ghazali als apoloqeet van de Islam, Leiden, 1947.

[4] G. Simon, Der Islam und die Christliche Verkűndigung, Giitersloh, 1920.

-

-

- H. Becker, “Christliche Polemik und Islamitische Dogmenbildung,” Islamstudien, I (Leipzig, 1924), 432-449. G. Graf, “Christliche Polemik gegen den Islam”, Gelbe Hefte, II, no. 2 (1926) 825-842.

-

[5] L. Cheikho, Vingts traités theoloqiques, znd. ed., Beyrouth, 1920, pp. 15-26.

[6] Printed in the margin of ،Abdarraḥmān, Bāčajīzāde: Al-fāriq bain al-makh- luq wal-khāliq, I (Kairo 1322/1905), 2-265.

[7] cf. E. Fritseh, I.e. pp. 28-31, 42. In this introductory part we mainly used this author for obtaining our material.

[8] (Kairo 1322/1905), 11, 71, 80, 81.

[9] Manuscript Utr. Cod. ms. or. No. 40; Leiden, Kataloog van de Goeje, No. 2703; esp. p. 91, 93, 94. cf. E. Fritsch, I.e. pp. 33 ff, 42.

[10] Written by Jalāl al-Dīn al-Maḥalli (died 1459) and Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūțī (died 1505).

[11] On these Commentaries and their explanations, cf. E. M. Wherry, A Comprehensive Commentary on the Quran, 4 vol. (London 1896), ad locum

[12] Qur. 19 : 48, 59 (Rodwell, p. 121) et passim.

[13] Qur. 5 : 26 (Rodwell, p. 488).

[14] Qur. 4 : 71 (Rodwell, p. 418).

[15] Qur. 5 : 10 (Rodwell, p. 487) et passim.

[16] Qur. 2 : lI6; 19 : 56 (Rodwell, pp. 350, 121).

[17] Qur. 5 : 70, 73. 88 (Rodwell, pp. 493 H.).

[18] Qur. 7 : 42, 43 (Rodwell, p. 297) an equivalent expression.

[19] Qur. 4 : 41 (Rodwell, p. 415).

[20] Qur. 4 : 10 f. (Rodwell, p. 4lI).

[21] Qur. 2 : 277 (Rodwell, p. 369).

[22] Qur. 4 : 26 H. (Rodwell, p. 413).

[23] Qur. 4 : 34 (Rodwell, p. 414).

[24] Qur. 4 : lI8; 17 : SI; 23 : ro8; 25 : ro; 25 : 18 (Rodwell, pp. 424, 168, ISO, 159, 160

[25] Qur. 27 : 43 (Rodwell, p. 177).

[26] Qur. 72 : 14 (Rodwell, p. 141).

[27] Qur. 4 : 47; 5 : IS (Rodwell, pp. 416, 487).

[28] Qur. 5 : 81 (Rodwell, p. 495).

[29] Qur. 20 : II9 (Rodwell, p. IOl).

[30] Qur. 26 : 19 (Rodwell, p. 104).

[31] Qur. 38 : 25 (Rodwell, p. 126).

[32] Qur. 26 : 91; 25 : 31 (Rodwell, pp. I06, 161).

[33] H. Gunkel-J. Begrich, Einleitung in die Psalmen (Gӧttingen, 1933). H. Gun-kel, “Psalmen”, Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, IV (1913), cols. 1927 ff.

[34] The most complete and systematic exposition on the literary forms in the Old Testament can be found in O. Eissfeldt, Einleitung in das Alte Testament (3rd ed.; Tϋbingen, 1964), pp. 14-170; about prophetic literary forms, ib. pp. 102- 108. For the convenantal rīb see esp. J. Harvey, “Le ‘Rîb-pattern,’ Réquisitoire prophétique sur la rupture de l’Alliance”, Biblica, 43 (1962), I72-196.

[35] D. Daube, “Rechtsgedanken in den Erzählungen des Pentateuch”, Beih. ZAW, 77 (1958), 32-41.

[36] G. Castellino, Il libro dei Salmi (Torino, 1955), pp. 808-813.

[37] See Jer. 6 : 16; 18: 15.

[38] Ps. 27 : 11; 86 : 11; 26 : 4; cf. Is. 2 : 3.

[39] 1 Sam. 9 : 6, 9.

[40] Judg. 18 : 5 f.

[41] 2 Kgs, 3 : 9-20.

[42] Num. 22 : 7-20; compare the divination of the king of Babylon, Ez. 21 : 26.

[43] ]. Begrich “Das priestliche Heilsorakel,” ZAW 52 (1934), 81-92.

[44] See also Tob. 10 : 12.

[45] Gen. 35 : 3.

[46] Gen. 24 : 27, 48.

[47] Tob. 11 : 1 ff

[48] Joel 2 :7; Jer. 18: 15; Mal. 2 :8; Pray. 14 :2; 1 Sam. 6: 12.

[49] Jer. 6 : 16; Ps. 139: 24.

[50] Ps. 37 : 14; 25 : 15, 19f; 27 : 11 ff; 5 : 8 ff; Esdr. 8 : 21-23.

[51] Jer. 18 : IS; Mal. 2 : 8; cf. Ps. 91 : 11ff; Tob. 5 : 21.

[52] Prov. 2: 7-15; 4 : 11-19; 14 : 2; 21 : 8; cf. 14 : 10; 1 Sam. 12 : 23; Is, 2 : 3.

[53] Prov, 12: 15; 14: 12; 16: 25; 21 : 2.

[54] Prov, 9 : 15; 11 : 20; cf. 15 : 19; 16 : 19; 21 : 29; 29 : 27.

[55] F. Cabrol, Liturgical Prayer, its History and Spirit (London, 1925), pp. 261-268.

[56] F. Cabrol, 1.c, (note 55), p. 267; see also the “Itinerarium” in the Roman Breviary and the Blessings for travellers in the Roman Ritual.

[57] From the Jewish manual of prayer: Siddur Auodat Israel (Tel Aviv, 1960), p. 141.

[58] Qur. 71 : 19 (Rodwell, p. 86).

[59] Qur. 43 : 9 (Rodwell, p. 135).

[60] Qur. 20 : 54; 67 : 15; 21 : 32 (Rodwell, pp. 96. 143, 153).

[61] Qur. 27 : 65 (Rodwell, p. 178); cf. Qur. 17 : 69 (Rodwell, p. 170).

[62] Qur. 17 : 28 (Rodwell, p. 167).

[63] Qur. 18 : 65-81 (Rodwell, pp. 186 ff).

[64] Qur. 18 : 82-98 (Rodwell, PP. 188 ff).

[65] Qur. 17 : 69 (Rodwell, p. 170).

[66] Qur. 17 : 71 (Rodwell, p. 170).

[67] Clergy Monthly, Suppl. to vol. 29 (March), 1965, vol. 7, no. 5, p. 188.

THE STORY OF MY LIFE

- » FOREWORD

- » Part One. LEARNING TO SURVIVE

- » origins

- » into gaping jaws

- » from the pincers of death

- » my father

- » my mother

- » my rules for survival

- » Part Two. SUBMIT TO CLERICAL DOGMA — OR THINK FOR MYSELF?

- » seeking love

- » learning to think

- » what kind of priest?

- » training for battle

- » clash of minds

- » lessons on the way to India

- » Part Three (1). INDIA - building 'church'

- » St John's Seminary Hyderabad

- » Andhra Pradesh

- » Jyotirmai – spreading light

- » Indian Liturgy

- » Sisters' Formation in Jeevan Jyothi

- » Helping the poor

- » Part Three (2). INDIA – creating media

- » Amruthavani

- » Background to the Gospels

- » Storytelling

- » Bible translation

- » Film on Christ: Karunamayudu

- » The illustrated life of Christ

- » Part Three (3). INDIA - redeeming 'body'

- » spotting the octopus

- » the challenge

- » screwed up sex guru

- » finding God in a partner?

- » my code for sex and love

- » Part Four. MILL HILL SOCIETY

- » My job at Mill Hill

- » The future of missionary societies

- » Recruitment and Formation

- » Returned Missionaries

- » Brothers and Associates

- » Part Five. HOUSETOP LONDON

- » Planning my work

- » Teaching teaching

- » Pakistan

- » Biblical Spirituality

- » Searching God in our modern world

- » ARK2 Christian Television

- » Part Five (2) New Religious Movements

- » Sects & Cults

- » Wisdom from the East?

- » Masters of Deception

- » Part Five (3). VIDEO COURSES

- » Faith formation through video

- » Our Spirituality Courses

- » Walking on Water

- » My Galilee My People

- » Together in My Name

- » I Have No Favourites

- » How to Make Sense of God

- » Part Six (1). RESIGNATION

- » Publicity

- » Preamble

- » Reaction in India

- » Mill Hill responses

- » The Vatican

- » Part 6 (2). JACKIE

- » childhood

- » youth and studies

- » finding God

- » Mission in India

- » Housetop apostolate

- » poetry

- » our marriage